Alternatives to institutions emerge in caring for dying people and their families

by Shannon Firth

When Lee Hoyt was in college her parents died — first her mother and then her father. Hoyt, now a retired teacher and volunteer at Gilchrist Hospice in central Maryland, said the losses were exacerbated by the abrupt separation from her parents.

“They were whisked away by the funeral home. It was done the conventional way, and no one talked to me about it,” she said.

Julie Lanoi, RN, a mental health clinician, hospice nurse and vice president of New Hampshire Funeral Resources Education and Advocacy (FREA) felt similarly about her own experience.

As a full time caregiver for both of her grandparents, Lanoi was upset by how quickly her grandmother’s body was taken from her when she died.

“It feels unnatural to me to have that distancing from the experience so quickly,” said Lanoi. “The person that you have loved your whole life is all of a sudden, they’re just gone out of the room, and you never see them again. Or you never see them again in that natural state.”

At the time, Lanoi was resigned to the process. “And then I realized there was another way to do it.”

Lanoi came across an article online on home funerals and “conscious dying.” The concept of “conscious dying” encourages conversation and decision-making, so that patients and families can make death and the bereavement process more meaningful and more intimate.

Both women are now what are variously called death doulas, death midwives, midwives to the soul, transition guides, psychopomps, and thanadoulas. They believe that there should be alternatives to institutions for people at the end of life, and to conventional afterlife care — that is, funerals — as well.

Interest in home funerals seems to be growing, particularly among providers. According to the National Home Funeral Alliance, 23% of its members are also medical providers — this includes doctors, nurses, and physical therapists. An additional 22.5% are spiritual care and social workers.

Still, said the group’s president, Lee Webster, “We are a death-denying a culture.”

“We’re the only creatures in existence that know we have a finite end,” she continued. “Not discussing it is ludicrous.”

The goal of home funeral guides is to walk patients and their families through the after-death process.

“We all want to feel that we’re not alone.”

Coaches, Fixers, Handholders

The role of death doulas or death and dying guides, as the Alliance calls them, is simple but important.

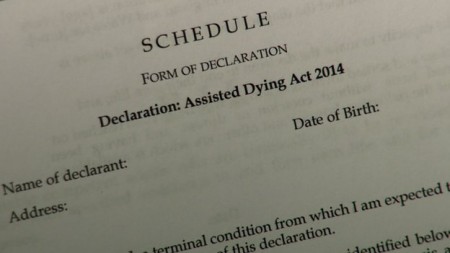

Patients will call on these individuals to help them write advanced directives, to plan wakes and funerals, and to help prepare their friends and family for what is about to happen. These guides can also help dying patients with the emotional and psychological work of forgiving injuries. “So that you can have a more peaceful ending to your relationships,” Hoyt said.

Many end-of-life guides will sit with families and offer support as patients are dying. Hoyt has also been called to the bedside of patients who have already died. She sat beside one man who had been dead 5 hours, while the family drove to the hospital. “The daughter was very grateful someone was there and that he hadn’t been alone,” she said.

After death, instead of having the patient’s body removed by a professional, Hoyt coaches family members in how to wash the body, properly rinse the mouth, shut the jaw, and dress him or her. It’s legal in all states for families to bathe a loved one, even after death, she said.

If the patient is in a hospital or nursing home, Hoyt can help families to complete the legal forms that would allow the family to bring a loved one home, if they wish to.

(Nine states mandate that families must engage with funeral homes. Webster’s group is actively lobbying to change this.)

While Hoyt is a volunteer, many guides and educators are paid for their work.

Jerrigrace Lyons, founder and director at Final Passages, in Sebastopol, Calif., charges an education fee to families of about $1,500 for the work she does over 3 or 4 days.

“I’m always willing to negotiate if people have a hardship with finances,” she said.

Although there is no legal license for death and dying guides, Lyons offers certification in end-of-life training. She conducts in-services at hospitals and sells guidebooks on end-of-life-care and occasionally speaks to medical students at universities.

Hoyt, who received her certification from Lyons, said, “The impetus for the movement in the beginning was healing, the really healing benefits of continuing to be engaged with the care, [and] providing a continuum of care for your loved one after death.”

The reason is obvious. “It keeps you busy and keeps you engaged in doing something that you know is very productive. It’s your final act of love,” she added.

While Hoyt could not rewrite the tragic experience of losing her parents, she was able to support the family of a close friend through her death and funeral process.

Hoyt remembers a house, filled with music, wind-chimes, and bird sounds. The windows were all open and the breeze blew into every room. Her friend lay in her bed barefoot in a favorite coat, under a giant pine bough. Then the family carried her friend in a seagrass casket strewn with lavender to a van that brought her to a burial site, where family and friends threw flowers into the air over her friends’ body.

“It was the most natural ritual that I’ve ever been a part of,” she said.

Guidance at a Distance

Lanoi’s role is to educate families so they can conduct patient-centered and family-directed funerals. She speaks with caregivers and relatives over the phone and holds workshops to share concrete practical and legal steps involved in the process.

She also connects families with traditional and nontraditional resources related to after-death options.

Lanoi said home funerals are not as unconventional as most people think.

“This is the way this was always handled for centuries and centuries and centuries,” she said.

“I think people have a fear that the body’s going to be decomposing before their eyes and it’s just, that’s not what happens.”

Conscious dying slows down the process and allows families to actively grieve their loss instead of setting themselves apart from it, she said. Many families of hospice patients have been bathing, toileting, dressing, and caring for their loved ones for years. That this should abruptly end because a person has died, and that an individual’s care be passed over to a stranger, seems odd to her.

“In caring for the body of the loved one for the last time, in washing the body for the last time, in having them be present with you after the death for a period of hours, it’s a very different experience than the ‘detaching from’ that we conventionally do, and we can miss out on some important emotional experiences,” she added.

When she speaks about her work with other medical colleagues, Lanoi said, “most of the time it’s been ‘Oh, I didn’t know you could do that.’ Some will even say, ‘That’s what I want.'”

When providers ask about the risk of infection, she advises home funeral guides to tell families to use the same universal precautions they would as when a patient was alive. Providers will also ask about their own liabilities. Once a death certificate is signed, “the medical world’s job is over,” she said.

Complete Article HERE!