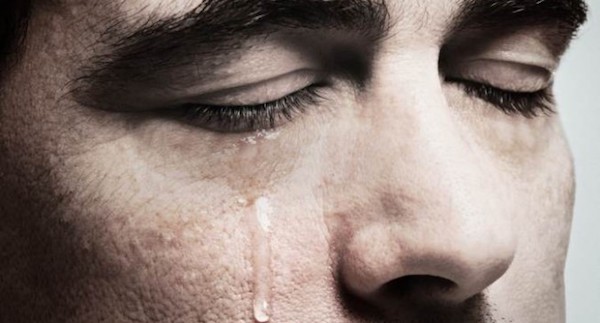

It is important to grieve the deal of a loved one or deal with loss the proper way says Dr Arun John. Find out why…

[I]magine that you injured yourself and there is a fresh, bleeding wound on your hand. Instead of letting the injury heal, you go about with your life ignoring that it even exists. Before you know it, the wound starts to fester, causing more pain and discomfort than before. What could have been fixed with a little bit of care and attention is now a big gaping wound that will take more time to heal.

Like physical wounds, your emotional wounds get worse when you ignore it. That’s probably why you hear people telling you to “cry it out” if you are going through a rough phase in your life.

Why some people don’t grieve

• Sadly, some of us hate showing the world we are vulnerable. We hate being perceived as powerless or weak. So we put on a brave face and make it seem like we aren’t hurt.

• Society sometimes dictates what we can and cannot grieve about. I was shamed for grieving for my pet cat who died in an accident last year. “It’s an animal, after all,” they would scoff!

• Sudden loss of a loved one or failure of a relationship can leave us stunned for a while, delaying the grieving process.

• We may want to put things behind us and move on with life and speed up the grieving process.

According to the Kübler-Ross model, a person undergoes five stages of emotions in the grieving process: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance. Skipping any of these steps can lengthen the grieving process causing more harm than good. Dr Arun John, executive vice president of the Vandrevala Foundation, who has a wealth of experience in dealing with bereavement and grief issues, tells us what could go wrong if we don’t grieve properly.

Self-blame

“Self-blame is a telltale sign of an incomplete grieving process,” says Dr John. If someone doesn’t grieve properly, they may get stuck at the bargaining stage. “They get obsessed and waste a lot of their time and energy investigating what went wrong and how they are to be blamed for it,” adds Dr John. “Usually, people blame themselves for a week or two, but if the self-blame extends for more than one month, the person could need help.”

Acute depression

“If the grieving process is not complete, the person could slip into acute depression,” says Dr John. Depression sets in when the person does not deal with his or feelings of grief appropriately. It may not show initially, but if the problem is not dealt with at the earliest, it may spill into his personal life and work. Prolonged depression can also become a cause for other health and mental problems.

Anxiety

According to Dr John, prolonged depression can also precipitate anxiety. When the loss is sudden or unexpected and if the person doesn’t give enough time for grief, he can slip into a state of stress and anxiety. In the case of a loved one’s passing, the idea of having seen death at such close quarters makes the person think about his own mortality.

Lifestyle diseases

It’s a known fact that stress, anxiety and depression can have serious effects on your health in the long run. Repressed negative emotions like fear and sadness cause elevated levels of cortisol in the blood. “It can lead to weight gain, hypertension and other lifestyle diseases,” says Dr John. Some may take to binge eating or drinking to escape confronting negative feelings; this can also affect their health adversely.

Whether it is a death of a loved one or a loss of a relationship, only you know the depth of your grief. Instead of bottling up your negative emotions, you should deal with it at the earliest. “Talking to loved ones speeds up the grieving process. If you feel no one understands you, feel free to call up a helpline number and talk to a counsellor.

Complete Article HERE!