If we learn to celebrate life for its ephemeral beauty, its coming and going, we can make peace with its end.

By George Yancy

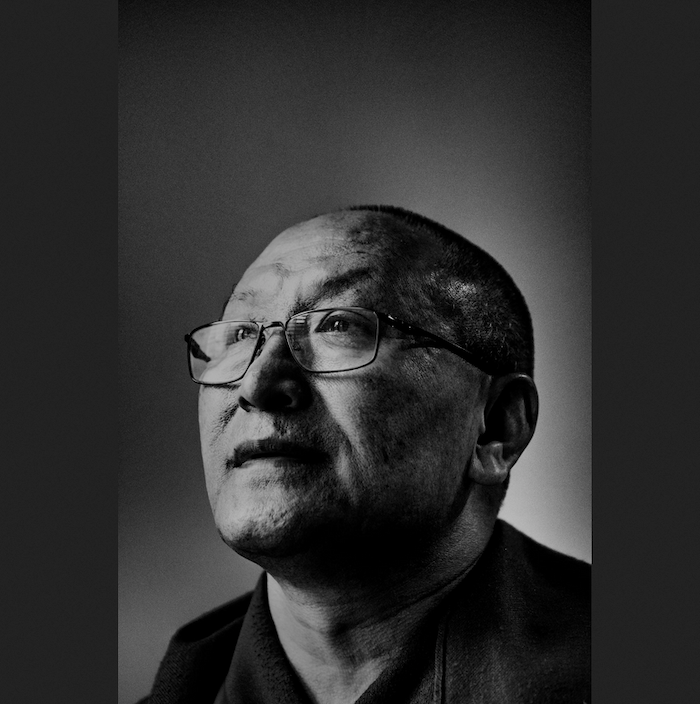

This is the first in a series of interviews with religious scholars from several faiths — and one atheist — on the meaning of death. This month’s conversation is with Geshe Dadul Namgyal, a Tibetan Buddhist monk who began his Buddhist studies in 1977 at the Institute of Buddhist Dialectics in Dharamsala, India, and went on to earn the prestigious Geshe Lharampa degree in 1992 at Drepung Loseling Monastic University, South India. He also holds a master’s degree in English Literature from Panjab University, Chandigarh, India. He is currently with the Center for Contemplative Science and Compassion-Based Ethics, Emory University. This interview was conducted by email. — George Yancy

George Yancy: I was about 20 years old when I first became intrigued by Eastern thought, especially Buddhism. It was the transformation of Siddhartha Gautama to the Buddha that fascinated me, especially the sense of calmness when faced with competing desires and fears. For so many, death is one of those fears. Can you say why, from a Buddhist perspective, we humans fear death?

Dadul Namgyal: We fear death because we love life, but a little too much, and often look at just the preferred side of it. That is, we cling to a fantasized life, seeing it with colors brighter than it has. Particularly, we insist on seeing life in its incomplete form without death, its inalienable flip side. It’s not that we think death will not come someday, but that it will not happen today, tomorrow, next month, next year, and so on. This biased, selective and incomplete image of life gradually builds in us a strong wish, hope, or even belief in a life with no death associated with it, at least in the foreseeable future. However, reality contradicts this belief. So it is natural for us, as long as we succumb to those inner fragilities, to have this fear of death, to not want to think of it or see it as something that will rip life apart.

We fear death also because we are attached to our comforts of wealth, family, friends, power, and other worldly pleasures. We see death as something that would separate us from the objects to which we cling. In addition, we fear death because of our uncertainty about what follows it. A sense of being not in control, but at the mercy of circumstance, contributes to the fear. It is important to note that fear of death is not the same as knowledge or awareness of death.

Yancy: You point out that most of us embrace life, but fail or refuse to see that death is part of the existential cards dealt, so to speak. It would seem then that our failure to accept the link between life and death is at the root of this fear.

Namgyal: Yes, it is. We fail to see and accept reality as it is — with life in death and death in life. In addition, the habits of self-obsession, the attitude of self-importance and the insistence on a distinct self-identity separate us from the whole of which we are an inalienable part.

Yancy: I really like how you link the idea of self-centeredness with our fear of death. It would seem that part of dealing with death is getting out of the way of ourselves, which is linked, I imagine, to ways of facing death with a peaceful mind.

Namgyal: We can reflect on and contemplate the inevitability of death, and learn to accept it as a part of the gift of life. If we learn to celebrate life for its ephemeral beauty, its coming and going, appearance and disappearance, we can come to terms with and make peace with it. We will then appreciate its message of being in a constant process of renewal and regeneration without holding back, like everything and with everything, including the mountains, stars, and even the universe itself undergoing continual change and renewal. This points to the possibility of being at ease with and accepting the fact of constant change, while at the same time making the most sensible and selfless use of the present moment.

Yancy: That is a beautiful description. Can you say more about how we achieve a peaceful mind?

Namgyal: Try first to gain an unmistaken recognition of what disturbs your mental stability, how those elements of disturbance operate and what fuels them. Then, wonder if something can be done to address them. If the answer to this is no, then what other option do you have than to endure this with acceptance? There is no use for worrying. If, on the other hand, the answer is yes, you may seek those methods and apply them. Again, there is no need for worry.

Obviously, some ways to calm and quiet the mind at the outset will come in handy. Based on that stability or calmness, above all, deepen the insight into the ways things are connected and mutually affect one another, both in negative and positive senses, and integrate them accordingly into your life. We should recognize the destructive elements within us — our afflictive emotions and distorted perspectives — and understand them thoroughly. When do they arise? What measures would counteract them? We should also understand the constructive elements or their potentials within us and strive to learn ways to tap them and enhance them.

Yancy: What do you think that we lose when we fail to look at death for what it is?

Namgyal: When we fail to look at death for what it is — as an inseparable part of life — and do not live our lives accordingly, our thoughts and actions become disconnected from reality and full of conflicting elements, which create unnecessary friction in their wake. We could mess up this wondrous gift or else settle for very shortsighted goals and trivial purposes, which would ultimately mean nothing to us. Eventually we would meet death as though we have never lived in the first place, with no clue as to what life is and how to deal with it.

Yancy: I’m curious about what you called the “gift of life.” In what way is life a gift? And given the link that you’ve described between death and life, might death also be a kind of gift?

Namgyal: I spoke of life as a gift because this is what almost all of us agree on without any second thought, though we may differ in exactly what that gift means for each one of us. I meant to use it as an anchor, a starting point for appreciating life in its wholeness, with death being an inalienable part of it.

Death, as it naturally occurs, is part of that gift, and together with life makes this thing called existence whole, complete and meaningful. In fact, it is our imminent end that gives life much of its sense of value and purpose. Death also represents renewal, regeneration and continuity, and contemplating it in the proper light imbues us with the transformative qualities of understanding, acceptance, tolerance, hope, responsibility, and generosity. In one of the sutras, the Buddha extols meditation on death as the supreme meditation.

Yancy: You also said that we fear death because of our uncertainty about what follows it. As you know, in Plato’s “Apology,” Socrates suggests that death is a kind of blessing that involves either a “dreamless sleep” or the transmigration of the soul to another place. As a Tibetan Buddhist, do you believe that there is anything after death?

Namgyal: In the Buddhist tradition, particularly at the Vajrayana level, we believe in the continuity of subtle mind and subtle energy into the next life, and the next after that, and so on without end. This subtle mind-energy is eternal; it knows no creation or destruction. For us ordinary beings, this way of transitioning into a new life happens not by choice but under the influence of our past virtuous and non-virtuous actions. This includes the possibility of being born into many forms of life.

Yancy: As a child I would incessantly ask my mother about a possible afterlife. What might we tell our children when they express fear of the afterlife?

Namgyal: We might tell them that an afterlife would be a continuation of themselves, and that their actions in this life, either good or bad, will bear fruit. So if they cultivate compassion and insight in this life by training in positive thinking and properly relating to others, then one would carry those qualities and their potential into the next. They would help them take every situation, including death itself, in stride. So, the sure way to address fear of the afterlife is to live the present life compassionately and wisely which, by the way, also helps us have a happy and meaningful life in the present.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!