We continue our sneak preview of the ten people who will be joining you in the on-the-page support group in The Amateur’s Guide To Death and Dying; Enhancing the End of Life. You’ll have plenty of opportunity to get to know them better once you start the book, but until then, these thumbnail sketches will serve as a handy reference.

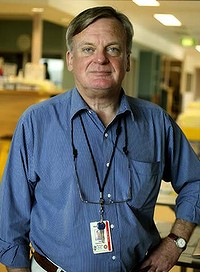

Raymond, 50, is a social worker employed by a home health care agency in San Francisco. He is thinking about applying for a position in the agency’s hospice program, but he’s not quite sure he’s ready for the responsibility. “I need to better understand my own feelings about death and dying before I can hope to assist anyone else.” He hopes this group will help him do this. “If I’m going to do this work, I want to do it well.”

Raymond, 50, is a social worker employed by a home health care agency in San Francisco. He is thinking about applying for a position in the agency’s hospice program, but he’s not quite sure he’s ready for the responsibility. “I need to better understand my own feelings about death and dying before I can hope to assist anyone else.” He hopes this group will help him do this. “If I’m going to do this work, I want to do it well.”

Raymond’s mother died of ovarian cancer when he was seven years old, but he never really processed the loss. Now a dear friend of long standing, Joann, is also dying of cancer. Joann’s imminent death has opened the floodgates of his unresolved grief associated with his mother’s death. “I’m both drawn to Joann and repulsed by her all at the same time. And she knows it. It’s so crazy. You should see me. I’m confused and disoriented, which is not at all like me.”

Raymond says that his interest in this group is strictly professional. “I don’t have a life threatening illness myself.” But upon further investigation, Raymond reveals that a recent visit to his doctor disclosed that he is at high risk for heart disease. Raymond is considerably overweight. “I guess I’ve pretty much let myself go to seed. I’ve always been a big guy, big-boned, as my mother would say, but now I’m just Fat with a capital ‘F’”. The heart disease news, while shocking, didn’t come as much of a surprise.

Three years ago Raymond went through a very acrimonious divorce. “My life shattered before my eyes.” His three children, two girls and a boy, live with his ex-wife in another state. He gets to see the kids only on holidays and for a month during the summer. “After the divorce, I just didn’t care if I lived or died. I ballooned. I put on over a hundred pounds in a matter of months. Hey, wait a minute. Maybe that’s why I’m considering this hospice move, and why I’m so ambivalent about Joann, and why I want to do this group. Maybe I need to recover a sense of meaning for my life.”