Jewish hospice chaplains confront the emotional and medical complexities of death and dying every day, but Holocaust survivors present special challenges.

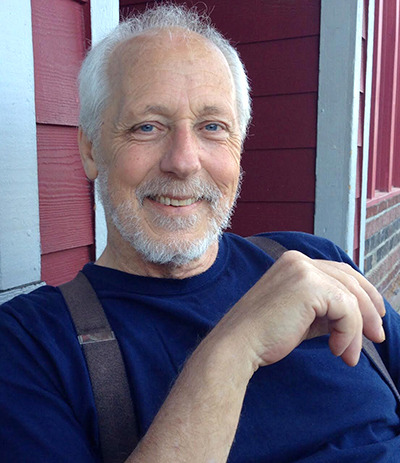

Rabbi E.B. “Bunny” Freedman, director of the Jewish Hospice and Chaplaincy Network, said that chaplains are increasingly being called on to provide spiritual support to survivors and their families.

“There are a lot of complex issues,” said Freedman, who has worked in end of life chaplaincy for 23 years. “One of them is making the decision of unhooking hydration – much more complex for a Holocaust family. The idea of not providing nutrition is crossing a sacred or not understood emotional line.”

Survivor guilt and mixed feelings at the prospect that they may “meet their relatives on the other side” commonly surface, he said.

Rabbi Charles Rudansky, director of Jewish clinical services at Metropolitan Jewish Health System’s hospice in New York, reported similar experiences with Holocaust survivors he had counseled.

“Last time they saw their loved ones was hellish, hellish, hellish, and now they’re crossing that bridge,” said Rudansky.

Some Holocaust survivors are apprehensive at that prospect, he said, while others are “uplifted.” A usually talkative person may fall silent, while a quiet person may suddenly have a lot to say.

“I’ve been called in by Holocaust survivors who only want to speak with me so some human ears will have heard their plight,” said Freedman.

Jan Kellough, a counselor with Sivitz Jewish Hospice and Palliative Care in Pittsburgh, said she encourages, but never pushes, survivors to share their stories. While it can be therapeutic for some survivors to talk about the Holocaust, she said, it is problematic for others.

For some survivors, “there’s an attitude of not wanting to give up, there’s a strong will to fight and survive,” said Kellough.

Children and grandchildren of survivors can also struggle to cope with their loved ones’ terminal illness, said Rudansky.

He said such people tell the hospice staff, “’My grandfather, my father survived Auschwitz. You can’t tell me they can’t survive this!’ They have great difficulty in wrapping their heads around this is different — this is nature.”

That difficulty can be compounded by the fact that children of survivors may not have had much contact with death in their lives, said Rabbi David Rose, a hospice chaplain with the Jewish Social Service Agency in Rockville, Maryland.

Because so many of their family members were wiped out in the Holocaust, children of survivors may be less likely to have experienced the death of a grandparent or aunt or uncle.

“That’s one of the benefits of hospice. We work with them and their families to help them accept their diagnosis,” said Kellough.

Hospice offers families pre-bereavement counseling, 13-months of aftercare and access to preferred clergy.

Special sensitivity is paid to spouses who are also survivors.

“Survivor couples, particularly if they met before the war or just after the war are generally exceptionally protective of each other,” said Rose. “A few different couples come to mind – every time I visited, the partner was sitting right next to their spouse, holding hands the whole visit.”

Freedman underscored that chaplains are trained not to impose their religious ideas on families, but rather to listen to the patient and family’s wishes.

“I tell the people I train that if you’re doing more [than] 30 percent [of the] talking in the early stages of the relationship, then you’re doing it wrong,” said Freedman.

“Seventy percent of communication is coming from your ears, your eyes, your smile — not your talking. Rabbis tend to be loquacious, we’re talkative,” he said. “But when I’m with a family, I am an open book for them to write on.”

Though the work is emotionally demanding, Freedman said, “Helping people through natural death and dying is one of the most rewarding things people can do.”

Complete Article HERE!