By John O. McManus

Death represents a significant and vulnerable point in time for both the individual facing it and his or her loved ones. As part of its Educational Focus Series, McManus & Associates, a top-rated estate planning law firm celebrating more than 25 years of success, today identified “10 Questions to Consider When Preparing for the Passing of a Loved One.” During a conference call with clients, the firm’s Founding Principal and AV-rated Attorney John O. McManus offered guidance on how to ensure optimal end-of-life care for oneself and loved ones. To hear his recommendations, go to http://bit.ly/2COi3R1.

“Death is an uncomfortable topic for many people, but it should be accepted as a natural part of life,” commented McManus. “While everyone would prefer to focus on life, a significant amount of stress related to death can be reduced by proper planning.”

10 Questions to Consider When Preparing for the Passing of a Loved One

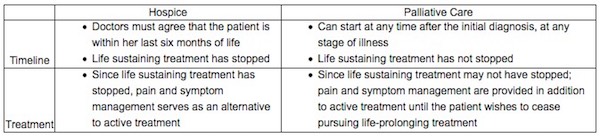

- Know one’s options: What is the difference between hospice and palliative care?

Both hospice and palliative care provide end-of-life care, including symptom management and comfort for an ill patient while he prepares for death. Both also offer end-of-life care in the home or in a facility and have a team of specialists who deliver this care. However, there are a few differences:

2. Dot your i’s and cross your t’s: Are all the necessary legal documents in order?

While competent, one’s loved one should express her wishes to guide family members in the event she cannot make decisions for herself. This includes directions as to what type of care she wants; whether she would like to donate her organs and when that should be communicated to medical professionals; preferred end-of-life care (hospice or palliative care) and location. This can be included in a health care directive or in a separate letter to the family but should be done with a greater level of formality – such as with the help of an attorney – to communicate the legitimacy of the loved one’s wishes.

- Health care directive/proxy: In this document, the loved one will appoint a surrogate decision-maker or proxy to make medical decisions for her once she is no longer considered able to make competent decisions and provide informed consent. Without this in place, family members will not be able to make medical or care decisions for their loved one; they will have to go through the courts to attain permission. This process can be time-consuming and expensive, detracting from the care of the patient.

- Living will: This document tells family members and surrogate decision-makers whether the loved one would like to receive additional measures of care. This includes instructions for extraordinary measures such as respirators, resuscitation, antibiotics, and withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining treatment. This is also a good place for the patient to instruct whether she would like her organs donated after her death.

- Health Insurance Portability & Accountability Act (HIPAA): This document protects the privacy of the patient’s medical records and other information. This is especially important if the loved one is unable to make competent decisions, allowing family members to get second opinions and to transfer her between facilities.

3. Broach the subject: Has there been a discussion with the loved one to understand what his or her wishes are?

Ultimately, the loved one should be in control of her death and family members should know what that means for her. When the time comes that she is no longer mentally competent to make her own decisions, her surrogate decision-maker will step in to be the voice of the patient. It is important for the surrogate decision-maker to keep in mind the patient’s wishes. This is by no means an easy conversation but can help bring peace of mind to the loved one knowing what a good death means to her is understood.

4. Nail down the timeline: When does the loved one want end-of-life care to begin?

Studies have found that there are many people who put off end-of-life care. This is often because the patient is still fighting his illness and does not want to receive end-of-life care until he is done receiving preventative treatment. This can minimize the benefits of end-of-life care, as he has less time to prepare for death. To be eligible for hospice care, patients must be within their last six months of life. If the loved one is not yet done fighting his illness, hospice may not be the right decision. If he wants to continue receiving preventative treatment, palliative care may be the better option. It is important to note that when hospice care starts, the loved one will no longer see his regular doctors, and will only be under the care of the hospice staff. However, if a new treatment becomes available while the loved one is receiving hospice care, he can leave hospice to receive life-prolonging treatment.

5. Research reputation: Has one discovered all that can be discovered about the potential care facilities being considered?

Not all facilities offer the same benefits. One should look at the reputation of each facility, and ask for references from them, in addition to looking up reviews online. One should also ensure that they provide quality care and do not have a history of promising services that were not delivered, and find answers to questions like, “Do they have a history of withholding pain medication from patients due to fear of addiction? Do they have a history of ethical or staff issues?” Additionally, one should ask when the last time the facility was inspected by the state or federal government, which should reveal if there were any issues. If there were, one should be sure that they were resolved.

6. Find out who is behind the mask: How well does one know the loved one’s care providers?

Few medical professionals have explicit training in death and dying. Talking to the loved one’s doctor may help form a more personal relationship and make the loved one feel more comfortable. Learning about the communication habits between the doctor and her colleagues is extremely important; one should be assured that all staff coming and going knows what has been done before they arrived and why. Also, as mentioned above, when the goal of end-of-life care is to provide comfort, reports of staff withholding pain medication can be an important concern. Finally, some facilities use volunteer services who interact with patients and their families, and learning what screening and training they have had can bring peace of mind.

7. Do due diligence: Has one done his or her own research? Have all factors that could influence one’s decision been explored?

Not all facilities are created equal. Hospice and palliative care have facilities across the nation; however, their standards vary. One should ask the facilities being considered for references. If anyone who has been in a similar situation is known, one should ask him or her how he or she was treated by the particular facility’s staff and if they followed through with their promises. Also, one should ask care providers to share what can be done by the patient’s loved ones to help. Most importantly, one should ensure that he or she is well-informed on the ethical issues in this area of care.

8. Learn the ins and outs: Is in-patient or out-patient care best for the loved one and family?

The physical location for end-of-life care is a significant decision for the loved one. It is important that she feels comfortable in her environment during the final days of her life. Unfortunately, this is not always possible to achieve, since some families may not be physically equipped to care for their loved ones at home (out-patient care) and some are not financially able to allow their loved ones to stay in a facility (in-patient care).

9. Prepare Plan B: Does one have a backup plan?

This may be most important for those who have decided to use out-patient care. Despite what promises are made by the end-of-life care provider, families should always have a backup plan. Recently, stories in the media have drawn attention to negative hospice and palliative care experiences. The reasons have ranged from poor communication to organizations not delivering on their promises. A common complaint is that staff does not treat the needs of patients who are in pain as time-sensitive, and the loved one’s doctors and nurses were unreachable. For situations such as these, it is important to have an alternative.

One option that many have found helpful is to have a comfort kit, which includes two pain relievers that can be administered to the loved one, should he be in pain when help is unable to come in a timely manner. One should ask for a comfort kit from the loved one’s care providers and shown how to properly administer the medication to the loved one.

10. Ask for help: Could the loved one and his or her family benefit from counseling?

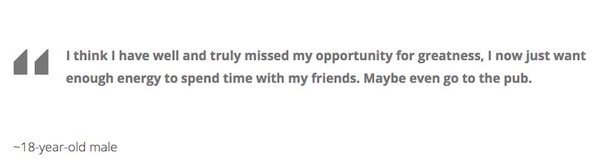

Death is a highly stressful process for the person who is dying and her friends and family. It is extremely important for all parties to feel informed about what they are undergoing. The loved one should be able to reach a point of finitude, coming to grips with eventual death – this is a long process that can occur on many levels. On a surface level, this can begin with preparing any necessary legal documents, and on a deeper level, this can include reminiscing, enjoying positive moments, saying goodbyes, passing on sentimental items of significance, and legitimizing her life how she sees fit. This should not solely be left for the loved one to realize on her own. When faced with a terminal diagnosis and death, people have many different reactions. It is important to offer the loved one guidance during this time. This will allow the loved one to have a death filled with control, dignity, peace, and finitude.

While this process has an end for the loved one, the family members must continue to live their lives. Rituals after death such as religious traditions, a funeral and/or a memorial service can be helpful, serving as a distraction and time to celebrate the loved one. However, at the end of this ritual period, family members will no longer have any distraction from their grief and may need guidance. It is important for those left behind to understand healthy coping techniques and the stages of grief they are experiencing.

“It is important to talk about death with loved ones – there are emotional benefits to reflecting on a life spent together, and expressing gratitude and admiration,” explained McManus. “It is also crucial to ask difficult questions so that the topic receives adequate attention and preparation

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!