By Sarah Gray

What people don’t understand is the beauty and joy to be found at the end of life. When I tell people I work at a hospice, they often say “that must be so hard.” But my favourite thing is hearing people’s stories, their experiences, their successes, their failures – the things that life has taught them. I love helping them share these stories with their family members. It helps the family members keep their loved one alive in their memories after he or she dies.

I had a husband of a resident come in six months after she had died to say that he received a Christmas card from her, written to him while in hospice. He was tearful, but so incredibly grateful for this gift. He said the card helped keep her alive for one last Christmas.

Hospice workers encourage conversations about things that want to be said and heard. We create time for families to connect, laugh and cry together. Mostly, we help create a legacy of the resident that will remain with their family.

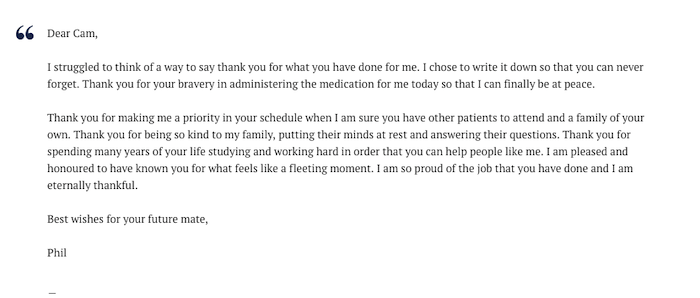

We have helped someone write letters to each of her children. We have sung favourite songs, played favourite games. We have celebrated birthdays, births, marriages, vow renewals. We have rolled people in their beds out onto the patio to sit in the sun. Often, this is their first time outside the four walls of a hospital or bedroom in months. How amazing it is to have such a thoughtfully designed building that can make this possible – feeling the warmth of the sun directly on their skin, hearing the birds chirping from the nearby feeder and breathing in the fresh air. I see how it provides the resident and their family with a sense of normalcy. This is where the best conversations happen. Families can forget, for a moment, about what is to come, and just enjoy the present.

Hospice is a place that collects nurses and personal support workers such as me. The emotionally challenging work we do weans out the people who think it’s just a job. You do not just show up for a shift, put in the time, and clock in and out. You are responsible for providing this human being, who has lived a whole life, with the care and dignity they deserve as they finish it. We help ensure that all loose ends are tied. Sometimes, these things are big, such as arranging a visit from a miniature pony that one of our residents used to show. Sometimes they are small, such as staff sitting at the bedside of a resident who doesn’t have any family, holding their hand, so they don’t die alone.

I have spent time working in hospitals, in long-term care and in the community as I searched for a place where the work that I did matched my beliefs of patient-centred care and individuality. After my first day at the hospice, I knew I had finally found my match. The loss of the residents we care for like family does not take a big piece of us with them but, rather, fills us with purpose and joy. The work we do gives us so much back that the word “rewarding” doesn’t even scrape the surface.

I began working at the hospice in May, 2017. As much as I love the work and what we accomplish, I could never have imagined needing it myself. Shortly after I started, my father was diagnosed with cancer. Soon we were faced with the decision I have seen so many other families struggle with: Do we settle for adequate care in the comfort of our home or do we move to the hospice where we will receive excellent care but in an unfamiliar location? The decision was easy for me, but not so much for my mom. She was afraid that moving him to hospice meant she was giving up her ability to care for her husband. But my mom was relieved to discover that she could still conduct much of the care, even in our facility. She did not have to sacrifice one for the other. With the 24/7 nursing and physician support, Dad – after eight months of suffering from his illness – finally had some peace.

During this time of comfort, he was able to give back to us something we will carry with us forever. He called us all in, on his last good day, told us all how much he loved us and reassured us that he never suffered. He was able to leave me with a recording, telling me what our relationship meant to him and that he would be with me through all of the big life events that he would now miss.

The hospice isn’t a place where people come to die. It is where they come to live – to live well for the little time they have left. It is a place of celebration, connection, comfort and support. It is a place of safety for the dying and the grieving. Experiencing such care with my father has only fuelled my passion to ensure that as many people as possible can have a similar experience.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!