From joining coffin clubs to downloading apps like WeCroak, here’s how a growing number of people are living their best life by embracing death.

by Stephanie Booth

Taking a dirt nap. Biting the big one. Gone — forever.

Given the gloom and painful finality with which we speak about death, it’s no wonder that 56.4 percent of Americans are “afraid” or “very afraid” of the people they love dying, according to a Chapman University study.

The cultural mindset is that it’s something terrible to be avoided — even though it happens to all of us.

But in recent years, people from all walks of life have begun to publicly push back against that oxymoronic idea.

It’s called the death positive movement, and the goal isn’t to make death obsolete. This way of thinking simply argues that “cultural censorship” of death isn’t doing us any favors. In fact, it’s cutting into the valuable time we have while we’re still alive.

What does that look like, exactly?

This rebranding of death includes end-of-life doulas, death cafes (casual get-togethers where people chat about dying), funeral homes that let you dress your loved one’s body for their cremation or be present for it.

There’s even the WeCroak app, which delivers five death-relevant quotes to your phone each day. (“Don’t forget,” a screen reminder will gently nudge, “you’re going to die.”)

Yet despite its name, the death positive movement isn’t a yellow smiley face–substitute for grief.

Instead, “it’s a way of moving toward neutral acceptance of death and embracing values which make us more conscious of our day-to-day living,” explained Robert Neimeyer, PhD, director of the Portland Institute for Loss and Transition, which offers training and certification in grief therapy.

Death as a positive mindset

Although it’s hard to imagine, what with our 24-hour news cycle that feeds on fatalities, death hasn’t always been such a terrifying prospect.

Well, at least early death was more commonplace.

Back in 1880, the average American was only expected to live to see their 39th birthday. But “as medicine has advanced, so has death become more remote,” explained Ralph White.

White is the co-founder of the the New York Open Center, an inspired learning center that launched the Art of Dying Institute. This is an initiative with a mission to reshape the understanding of death.

Studies show that 80 percent of Americans would prefer to take their last breath at home, yet only 20 percent do. Sixty percent die in hospitals, while 20 percent live their last days in nursing homes.

“Doctors are trained to experience the death of their patients as failure, so everything is done to prolong life,” White said. “Many people use up their life savings in the last six months of their lives on ultimately futile medical interventions.”

When the institute was founded four years ago, attendees often had a professional motivation. They were hospice nurses, for instance, or cancer doctors, social workers, or chaplains. Today, participants are often just curious individuals.

“We consider this a reflection of American culture’s growing openness to addressing death and dying more candidly,” White said.

“The common thread is that they’re all willing to engage with the profound questions around dying: How do we best prepare? How can we make the experience less frightening to ourselves and others? What might we expect if consciousness continues after death? What are the most effective and compassionate ways of working with the dying and their families?”

“The death of another can often crack us open and reveal aspects of ourselves that we don’t always want to see, acknowledge, or feel,” added Tisha Ford, manager of institutes and long-term trainings for the NY Open Center.

“The more we deny death’s existence, the easier it is to keep those parts of ourselves neatly tucked away.”

Death as a community builder

In 2010, Katie Williams, a former palliative care nurse, was attending a meeting for lifelong learners in her hometown of Rotorua, New Zealand, when the leader asked if anyone had new ideas for clubs. Williams did. She suggested she could build her own coffin.

“It was a shot from somewhere and totally not a considered idea,” said Williams, now 80. “There was no forward planning and little skill background.”

And yet, her Coffin Club generated massive interest.

Williams called up friends between the ages of 70 and 90 with carpentry or design skills she thought could be useful. With the help of a local funeral director, they began building and decorating coffins in William’s garage.

“Most found the idea appealing and the creativity exciting,” said Williams. “It was an incredible social time, and many found the friendships they made very valuable.”

Nine years later, although they’ve since moved to a larger facility, Williams and her Coffin Club members still meet every Wednesday afternoon.

Children and grandchildren often come too.

“We think it’s important that the young family members come [to] help them to normalize the fact that people die,” explained Williams. “There’s been so much ‘head in the sand’ thinking involved with death and dying.”

Younger adults have shown up to make coffins for terminally ill parents or grandparents. So have families or close friends experiencing a death.

“There’s lots of crying, laughing, love and sadness, but it has been very therapeutic as all ages are involved,” said Williams.

There are now multiple Coffin Clubs across New Zealand, as well as other parts of the world, including the United States. But it’s less about the final product and more about the company, Williams pointed out.

“It gives [people] the opportunity to voice concerns, get advice, tell stories and mingle in a free, open way,” said Williams. “To many who come, it’s an outing each week that they cherish.”

Death as a life changer

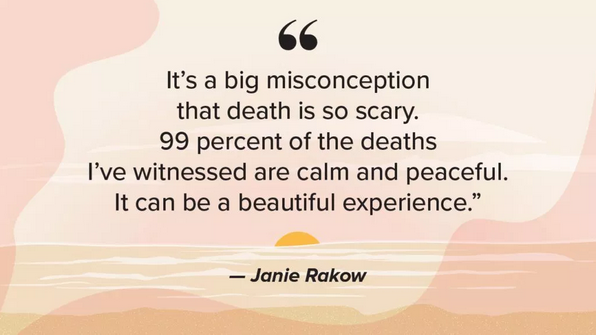

Janie Rakow, an end-of-life doula, hasn’t just changed her life because of death. She helps others do the same.

A corporate accountant for 20 years, Rakow still vividly remembers being mid-workout at a gym when planes struck the World Trade Towers on September 11, 2001.

“I remember saying to myself, ‘Life can change in one second,’” said the Paramus, New Jersey, resident. “That day, I wanted to change my life.”

Rakow quit her job and started volunteering at a local hospice, offering emotional and spiritual support to patients and their families. The experience profoundly changed her.

“People say, ‘Oh my gosh, it must be so depressing,’ but it’s just the opposite,” Rakow said.

Rakow trained to become an end-of-life doula and co-founded the International End of Life Doula Association (INELDA) in 2015. Since then, the group has trained over 2,000 people. A recent program in Portland, Oregon, sold out.

During a person’s last days of life, end-of-life doulas fill a gap that hospice workers simply don’t have the time for. Besides assisting with physical needs, doulas help clients explore meaning in their life and create a lasting legacy. That can mean compiling favorite recipes into a book for family members, writing letters to an unborn grandchild, or helping to clear the air with a loved one.

Sometimes, it’s simply sitting down and asking, “So, what was your life like?”

“We’ve all touched other people’s lives,” said Rakow. “Just by talking to someone, we can uncover the little threads that run through and connect.”

Doulas can also help create a “vigil plan” — a blueprint of what the dying person would like their death to look like, whether at home or in hospice. It can include what music to play, readings to be shared aloud, even what a dying space may look like.

End-of-life doulas explain signs of the dying process to family and friends, and afterward the doulas stick around to help them process the range of emotions they’re feeling.

If you’re thinking it’s not so far removed from what a birth doula does, you’d be correct.

“It’s a big misconception that death is so scary,” said Rakow. “99 percent of the deaths I’ve witnessed are calm and peaceful. It can be a beautiful experience. People need to be open to that.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!