— For the second year in a row, life expectancy in the U.S. declined—this time to the lowest level since 1996.

That marks a disturbing turn from the historical trend. In 1900, U.S. life expectancy was 47 years, and by 2019 it hit 79. But in 2020, life expectancy fell to 77 and dropped further to 76.4 in 2021, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

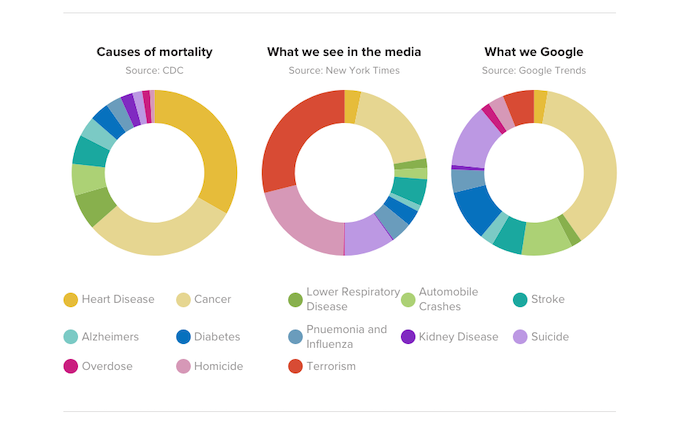

This alarming trend is clearly not an anomaly and is primarily due to heart disease, cancer, COVID-19 and the ongoing drug-overdose epidemic. Heart disease remains the leading cause of death, followed by cancer and COVID-19, which accounted for about 60% of the decline in life expectancy. Meanwhile, overdose deaths—which account for more than one-third of all accidental deaths in the United States—have risen five-fold over the past two decades.

The AMA’s What Doctors Wish Patients Knew™ series provides physicians with a platform to share what they want patients to understand about today’s health care headlines, especially throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

In this installment, three physicians took time to discuss what patients need to know about declining U.S. life expectancy. They are:

- Sandra Fryhofer, MD, an Atlanta general internist and chair of the AMA Board of Trustees. Dr. Fryhofer also serves as the AMA’s liaison to the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and is a member of ACIP’s COVID-19 Vaccine Work Group.

- Bobby Mukkamala, MD, an otolaryngologist in Flint, Michigan, and immediate past chair of the AMA Board of Trustees. Dr. Mukkamala is also chair of the AMA Substance Use and Pain Care Task Force.

- Charles Wilmer, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Piedmont Heart Institute in Atlanta and an alternate delegate in the AMA House of Delegates for the Medical Association of Georgia.

People are dying younger

“What’s interesting is you would expect it to be all older people who died,” Dr. Wilmer said. “If you look at infant mortality, it didn’t change at all. If you looked at people less than 25 years old, the mortality only went up 2.5%.”

For those “65 or older, their mortality was higher, it increased by 20%. What’s interesting is the 25- to 35-year-old group increased 24% and the 35- to 44-year-old group increased the most,” he said.

The decline in life expectancy isn’t just about shaving years off older adults. It’s also about more people dying younger, which was seen “with COVID and accidents, one-third of which are from overdose,” Dr. Mukkamala said.

While people 65 or older are at risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19, that population has higher vaccination rates than younger adults. As a result, we’ve seen people under the age of 65 dying from COVID-19. Overdose deaths are less likely in those over the age of 65, they are most common among those 25–54 years old.

Overdose “can be the cause of death as well, but it’s not something that is particular to the elderly,” he said, noting that overdose deaths are “even more alarming—that it’s not something that’s taking years off the end of our life. It’s taking people out of life in their younger years.”

Several factors led to the decline

“The decline in life expectancy was thought to be due mostly to COVID-19. Suicides, homicides, chronic liver disease and cirrhosis all went up,” Dr. Wilmer said. “There’s been a lot more drinking, a lot more alcohol, less socialization and more liquor being consumed.”

“Liver disease bumped influenza and pneumonia to be one of the top 10 causes of mortality for the first time. And then unintentional injuries including overdose,” he said. “So, there are a number of things that led to this decreased life expectancy.”

“The second thing is that when you have pandemics, the access to health care drops. So, the person has a worse diet, it’s more difficult for them to get their medicines and they’re less focused on taking their medicines,” Dr. Wilmer said. On top of that, “they sleep more poorly, they eat ultraprocessed foods that have a lot of sodium that leads to higher blood pressure. And then of course there’s loneliness.”

Overdose deaths are at a record high

“Overdoses are one-third of all the accidental deaths. In the last 20 years, this has gone up five times,” Dr. Wilmer said. “We have got to come up with a better plan for preventing overdoses.”

“The American Medical Association has been working on this for many years and initially the focus was internally focused, looking at physicians and our prescribing habits. We learned a lot from that introspection,” said Dr. Mukkamala. “That first phase was looking internally and saying: What can we change about our prescribing habits so there’s not so much narcotic out there?”

“And we did those things. The amount of prescribing that physicians have done for opioids has dropped by almost 50% in the past several years. Yet we are at a record number of deaths associated with overdoses,” he said. “That’s what made us realize that the next chapter in the history of substance-use disorder and opioid-related deaths in this country isn’t coming from exam rooms and operating rooms.

“It’s coming from out there in our communities because of illicit fentanyl and heroin that’s driving the record number of deaths,” Dr. Mukkamala added. “That’s why we’re seeing a decrease in life expectancy and that younger segment of the community that’s having a record number of deaths associated with illicit drugs.”

Access to naloxone isn’t enough

Over-the-counter access to the opioid-overdose antidote naloxone is “one critical piece of the solution, not the saving grace of everything related to substance-use disorder and the record number of deaths,” said Dr. Mukkamala. “But certainly, the more naloxone that’s available, the more lives we can save.”

“What we also see from those who work with patients with substance-use disorder is that naloxone is an intervention that saves their life at the very end of that behavior,” he said. “It doesn’t solve the underlying problem that led to that critical moment.

“And if they still have a substance-use disorder, they’re still going to use after that. So the danger in that isolated event is oftentimes not enough to stop them,” Dr. Mukkamala added. “Treating them with naloxone is one element of the solution, but dealing with their underlying mental health issues, getting them treatment, getting them on something like buprenorphine can help before it gets worse.”

Heart disease is still a leading cause

“There are multiple factors that lead to heart disease: hypertension, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes and smoking,” said Dr. Mukkamala. “These are all factors that can lead to heart disease and why we’re still seeing that at such a high level is because all of these factors are at high levels.”

“At the AMA, we’ve really made an effort to deal with some of those precursors. It’s great to save somebody’s life when they get chest pain … but it would be more wonderful to prevent them from that crisis,” he said. That’s “because we can’t save everybody in that moment, but we sure can reduce the number of people who end up in that crisis situation by making sure that if somebody has prediabetes, that we alert them of that long before they have any symptoms of diabetes.”

“And same thing with hypertension. How great would that be to alert somebody? Stage one hypertension doesn’t usually cause symptoms, but we can find it,” said Dr. Mukkamala. “It’s no different than getting checked for prostate cancer or getting a pap smear for a gynecologic exam. These screening interventions help to find disease before it causes a bigger problem.”

“There has not only been significant change in care for diabetes and blood pressure, but there’s also been much improvement in cholesterol and lipid management,” said Dr. Wilmer. This has “brought down the heart disease mortality and risk.”

Misinformation has run rampant

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, “politics have also come into play as vaccines and masking become political hot buttons and misinformation spread through social media platforms became rampant,” Dr. Fryhofer said, acknowledging that “people are tired of the pandemic.”

“We in the U.S. have access to vaccines. We have access to COVID therapeutics, but our life expectancy is among the lowest of wealthy countries,” falling by 2.7 years from 2019 to 2021, she said. “Political polarization and misinformation likely play a role.”

We have the resources for change

While “COVID-19 has now gone from pandemic to endemic, we are at a different place than we were in January 2020,” she said. “We now have vaccines. There is now hybrid immunity from infection and vaccination—two exposures to the spike protein from the vaccination or infections provide some degree of protection.

“But read the fine print—only if you survive infection,” Dr. Fryhofer said, emphasizing that “the new bivalent Omicron booster is effective. It works against current circulating strains including XBB.1.5, but more people need to get it.”

“COVID-19 is not gone. It’s still here and the virus is evolving. We don’t know which variant is next but for the one that’s currently circulating, this bivalent vaccine has your back,” Dr. Fryhofer.

Cancer is still so prevalent

“It’s a devastating disease and we’re getting better at treating it. We’re getting better at detecting it, but it’s still so prevalent,” said Dr. Mukkamala. “It’s not that we’re getting worse at the treatment of cancer. It’s just such a prevalent disease that the number is going to be high for a long time to come.”

“And that’s why we are still focused—just like with these other diseases—at finding it early with appropriate preventive screening measures,” he added. “Colon cancer and breast cancer are right at the top of that list, and these are all things that we can screen for so that we can detect them early before they become more symptomatic, dangerous and advanced.”

Screenings for cancer have fallen

“The other part that’s a little bit more difficult is people didn’t come in for routine cancer screenings during the pandemic,” Dr. Wilmer said. “So, all of a sudden, now patients are showing up a year, two years later with more advanced cancers as well as more cancers that could have been stopped earlier.”

“Breast and lung cancer screenings have dropped since the pandemic began, which could likely translate into delayed cancer diagnosis and an increase in cancer deaths,” Dr. Fryhofer said. Unfortunately, “breast and lung cancer screenings haven’t bounced back after a pandemic pause.”

“A recent study in JAMA Network Open suggests decreases in cancer screenings seen early in the pandemic have not resolved,” she said, noting that lung scans dropped 24% in the first pandemic year and 14% in the second. For breast-cancer screening, there were 17% fewer mammograms in the first year and 4% fewer in the second.

Don’t panic, but don’t ignore it

Knowing that life expectancy in the U.S. has declined is “not a reason to panic, but something that shouldn’t be ignored,” Dr. Mukkamala said. “Changing the way we take care of ourselves and our loved ones is going to be an important outcome.”

There is “no reason to panic about it, but it shouldn’t be ignored otherwise we end up with more than a two-year trend of a downward life expectancy,” he said. “It’s only through effort—not by luck—that we will go in the right direction again.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!