Like so many other injustices, the pandemic has only magnified the problems Black people face in the death and dying space. These women are working to solve them.

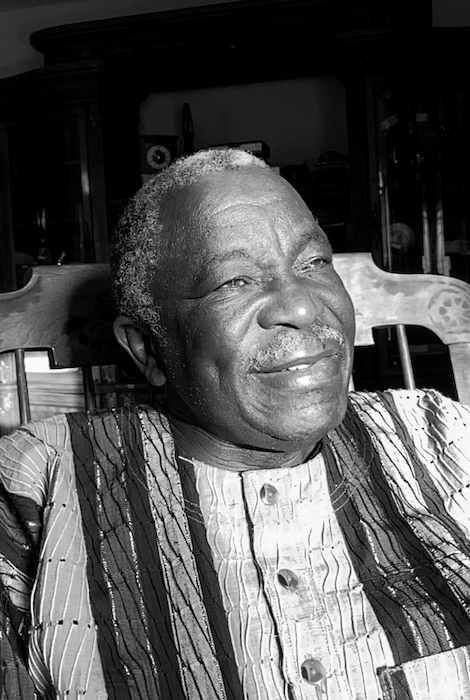

Joél Simone Anthony is in her mother’s sunlit living room in Beaufort, South Carolina. She’s wearing a black long-sleeved mock neck shirt with a fresh twist out, a bold red lip, and large silver earrings that jangle like windchimes. “I live in Atlanta, Georgia, but I’m getting married and my mom had surgery, so I’m actually here taking care of her and planning my wedding and everything,” she warmly shares with me over Google Meet.

There’s something about Anthony — a full-time sacred grief practitioner — and her amenity that strikes me at that moment. Perhaps it’s because one wouldn’t expect a person whose business moniker is The Grave Woman to be so rosy; one of the misconceptions people have of those who work in the death and dying space is that the work has to be sad, she shares later in our exchange. But it’s also clear to me early on in our conversation that working as a licensed funeral director and sacred grief practitioner is more than a profession for Anthony — it’s her calling.

“Let me just start off by saying that this is something my ancestors literally gave me a title for in 2020,” she says when I ask her to describe what a sacred grief practitioner does. Her work inside funeral homes — which she had been doing for almost 10 years — was transitioning to teaching online courses amidst the pandemic. Unsure of what direction she was moving in, she went into prayer and meditation about what to call herself. “The ancestors spoke to me [and said] that the name for [what I was doing] was sacred grief practitioner,” she says.

This spiritual calling is indicative of the relationship that Black folx have with death and dying. While death is considered a taboo topic to some, it’s celebrated as a moment of joy in many Black communities — a homegoing in which those who have transitioned no longer have to endure the earthly troubles of the world. “It’s a celebration of the fact that the person who’s passed away, their spirit is now able to return to their homeland, which is tied very deeply to our history with slavery,” Anthony explains. “Those that were celebrating, or allowed to celebrate, the lives of their loved ones through funeralization did not see this place as their home. They weren’t just celebrating the fact that someone passed away like our European captors were doing; we were celebrating the fact that our ancestors or our loved ones’ spirits were now able to return home.”

When it comes to death and dying, I think that people think that the playing field is equal. People really believe in their hearts that all the bullsh*t ends in death. It doesn’t.

Joél simone anthony

This history is deeply embedded in Anthony’s work. Her home, Beaufort County’s Port Royal Sound, is where just about every African-American can trace their ancestors being brought into this country as enslaved people, she says (slave importations occured in Beaufort County between 1730 and 1776). “That alone should set the foundation for what energy resonates in this place.” It is also home to Gullah and Geechee culture, which has ties to Central and West Africa, in which death is regarded as a rite of passage through which a spirit transitions into the next realm. Funeral directors like Anthony have been instrumental in preserving Black homegoings. During these ceremonies, bodies are typically viewed in an open casket that’s been decorated with a lush presentation of flowers and other decorations. Limousines will often escort families to homegoing services. It’s a moment of mourning, but it’s also one of pride. “To give a peaceful, celebratory homegoing, it’s the whole idea of a celebration of life,” Karla F.C. Holloway, a professor of English, law, and African American studies at Duke University, told The Atlantic in 2016. “It is a contradiction to the ways in which many Black bodies come to die.”

Creating this contradiction has become central to many Black people working in the death and dying industry, and why it’s become increasingly important to decolonize it. During the summer of 2020, Going With Grace founder Alua Arthur hosted Sayin’ It Louder, a panel discussion (including Arthur, Anthony, and other Black grief practitioners: Alica Forneret, Naomi Edmonson, Oceana Sawyer, and Lashanna Williams) about being Black in the death and dying industry during the time of COVID. George Floyd had just been murdered, and there was a conversation happening regarding how to “confront racism disguised as implicit bias that exists against Black workers, Black deceased people, and patrons of their families.” There was also a call to create an accessible and centralized database of grief resources for Black people.

“We had a lot of interest. I think about 7500 people signed up, but what I found more fascinating about that was that, prior to that time, I was the most visible Black person in death and dying,” says Arthur, who also has experience as a death doula, a person who manages the non-medical care and support of a dying person and their family. “People would call Going With Grace and be like, ‘Is this the Black Death Doula?’ or ‘You’re Black, right?’ These are people that wanted a Black person to be with them.”

Like so many other injustices, the pandemic has only magnified the problems Black people face in the death and dying space. “The inequities in the way we live and die could not have become more apparent during this time, coupling both the pandemic and social movements we’ve witnessed in the last two years,” says Alica Forneret, grief consultant and founder of PAUSE, an organization focused on creating spaces that produce safe, culturally-specific, and expert-informed grief and end of life resources serving for Black and brown communities. “Starting PAUSE felt timely, important, and urgent.” she continues. “What I want above anything in this work is for people to feel like they aren’t alone in death OR in the processing of a death that’s happened in their community. To me, the way to ensure that is access to education, culturally relevant resources, and people who will guide us through the inevitable end with compassion, patience, and attention to our unique needs.”

Space is now being created for people that fit outside the dominant culture to have access to people, to support them through death and dying. I want to keep that going as long and as far as I can.

Alua Arthur

The death and dying space has historically been a largely white industry, says Arthur. This is reflected in both the visibility of Black and brown folks working within it and the training resources that are available to those who want to join.”When it comes to death and dying, I think that people think that the playing field is equal. People really believe in their hearts that all the bullsh*t ends in death. It doesn’t,” says Anthony, who has witnessed the mistreatment and mishandling of Black bodies inside funeral homes, whether due to ignorance or blatant carelessness. This is also why spaces like Arthur’s Going With Grace, a death doula training and end-of-life planning organization, are so necessary. “When I went to other training programs, I was sitting with a bunch of white folx. But in the last three years since the training program has been up and running, a big portion of our courses are people of color, women of color, people who are trans and non-binary and queer,” says Arthur. “Space is now being created for people that fit outside the dominant culture to have access to people, to support them through death and dying. I want to keep that going as long and as far as I can.”

In addition to training programs run by Black folx creating space for the marginalized to flourish within the industry, it also ensures that postmortem care is thoughtful and inclusive. “I can remember working in a funeral home and going into the embalming room where people are cared for, and a licensed professional who was training me was cutting a Black woman’s box braids out from her scalp,” Anthony recalls. “[He isn’t] thinking that he’s doing anything wrong, not doing it maliciously. The family told him they wanted the braids out, but [he] simply did not understand that her hair is intertwined in these braids that he’s cutting out.” Anthony was grateful she walked in the moment she did and was able to stop him, but situations like this are prime examples of why more standardized education that includes Black and brown folx is needed in this space. ”If it were a white woman, you would understand that you have to shampoo her hair and brush her hair a certain way. Why is that? Why is this something that you were not taught as a licensed professional?”

Around the same time as Sayin’ It Louder, Anthony and her mentor Anita Pollard Grant — a registered nurse and licensed mortician — released a Racism in Death Care course. “All of the praise and all of the accolades that we’re receiving for having these conversations as Black women is wonderful, but will this support exist a year from now?” she says, echoing her sentiments from the panel. “I feel the conversations being had by people that look like me have been happening and need to happen; however, in some ways, the energy is different,” she continues. “The timing was right for the conversation and for the projects built around it. But I don’t feel like the conversation needs to end because there’s no more media coverage on what’s happening to Black and brown people.”

Continuing the conversation of equity in the death and dying space is something that Arthur also feels very strongly about and hopes to see change. “I’m also grateful that you’re writing this piece,” she tells me. “I hope that what happens is that we’re able to continue to diversify the voices of Black people and [death] care.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!