NHS end-of-life and palliative care must focus more on the dying person’s needs and wishes – but for that we need to have proper conversations

By Jon Henley

My father spent 10 days dying.

He was 84 and he had lost his wife – my mother, whom he adored, and without whom he felt life was a lot less worth living – three years earlier. He died of old age, and it was entirely natural.

The process, though, did not feel that way at all, at least not to me. Dad had been bedridden for months and was in a nursing home. He stopped eating one day, then started slipping in and out of consciousness. Soon he stopped drinking.

For 10 days my sister and I sat by his bedside, holding his hand, moistening his lips. Slowly his breathing changed, became more ragged. During the last few days, the tips of his fingers turned blue. His skin smelled different. His breath gradually became a rasp, then a rattle.

It sounded awful. We were sure he was in pain. The doctor reassured us he wasn’t; this was a human body dying naturally, shutting down, one bit at a time. We had not, of course, talked about any of this with Dad beforehand; we had no plans for this, no idea of what he might have wanted. It would have been a very difficult conversation.

The doctor said he could give him something that would make him at least sound better, but it would really be more for us than for my father. “My job,” the doctor said, “is about prolonging people’s lives. Anything I give to your father now would simply be prolonging his death.”

So we waited. When it finally came, death was quite sudden, and absolutely unmistakable. But those 10 days were hard.

Death is foreign to us now; most of us do not know what it looks, sounds and smells like. We certainly don’t like talking about it. In the early years of the 20th century, says Simon Chapman, director of policy and external affairs at the National Council for Palliative Care, 85% of people still died in their home, with their family.

By the early years of this century, fewer than 20% did. A big majority, 60%, died in hospital; 20% in care homes, like my father; 6% in hospices, like my mother. “Death became medicalised; a whole lot of taboos grew up around it,” Chapman says. “We’re trying now to break them down.”

There has been no shortage of reports on the question. From the government’sEnd of Life Care Strategy of 2008 through Julia Neuberger’s 2013 review of the widely criticised Liverpool Care Pathway to One Chance to Get it Right, published in 2014, and last year’s What’s Important to Me [pdf] – the picture is, gradually, beginning to change.

The reports all, in fact, conclude pretty much the same thing: the need for end-of-life care that is coordinated among all the services, focused on the dying person’s needs and wishes, and delivered by competent, specially trained staff in (where possible) the place chosen by the patient – which for most people is, generally, home.

“It’s not just about the place, though that’s important and things are moving,” says Chapman: the number of people dying in hospital has now dropped below 50%.

“The quality of individual care has to be right, every time, because we only have one chance. It’s about recognising that every patient and situation is different; that communication is crucial; that both the patient and their family have to be involved. It can’t become a box-ticking exercise.”

Dying, death and bereavement need to be seen not as purely medical events, Chapman says: “It’s a truism, obviously, but the one certainty in life is that we’ll die. Everything else about our death, though, is uncertain. So we have to identify what’s important to people, and make sure it happens. Have proper conversations, and make proper plans.”

All this, he recognises, will require “a shift of resources, into the community” – and funding. Key will be the government’s response to What’s Important to Me, published last February by a seven-charity coalition and outlining exactly what was needed to provide full national choice in end-of-life care by 2020. It came with a price tag of £130m; the government is expected to respond before summer.

In the meantime, though, a lot of people – about half the roughly 480,000 who die in Britain each year – still die in hospital. And as an organisation that has long focused on curing patients, the NHS does not always have a framework for caring for the dying, Chapman says.

But in NHS hospitals too, much is changing. There has been a specialist palliative care service – as distinct from end-of-life care, which is in a sense “everyone’s business”, involving GPs, district nurses and other primary care services – at Southampton general hospital and its NHS-run hospice, Countess Mountbatten House, since 1995, says Carol Davis, lead consultant in palliative medicine and clinical end-of-life care lead.

People die in hospital essentially in five wards: emergency, respiratory, cancer, care of elderly people and intensive care, she says: “Our job is about alleviating patients’ suffering, while enabling patients and their families to make the right choices for them – working out what’s really important.”

Palliative care entails not just controlling symptoms, but looking after patients and their families and, often, difficult decisions: how likely is this patient get better? Is another operation appropriate? What would the patient want to happen now (assuming they can’t express themselves)? Has there been any kind of end-of-life planning?

Of course many patients in acute hospital care will not be able to go home to die, and some will not want to, Davis says: “Some simply can’t be cared for at home. If you need two care workers 24/7, it’s going to be hard. Others have been ill for so long, or in and out of hospital so often, they feel hospital is almost their second home. So yes, choice is good – but informed choice. The care has to be feasible.”

In 2014, the report One Chance to Get it Right [pdf] identified five priorities in end-of-life care: recognise, communicate, involve, support, and plan and do. (“Which could pretty much,” says Davis, “serve as a blueprint for all healthcare.”) The first – recognise, or diagnose – is rarely easy. How does a doctor know when a patient is starting to die?

“There are physical signs, of course,” says Davis. “Once the patient can’t move their limbs, or can no longer swallow.” But, she says, “we have patients who look well but are very ill, and others who look sick but are not. In frail elderly people – or frail young people – it can be hard to predict. Likewise, in patients with conditions like congenital heart disease, where something could happen almost at any moment.”

Quite often, Davis and her team face real doubts. “Right now,” she says, “I have a patient in intensive care, really very ill. They probably won’t pull through, but they might. I have another doing well, making excellent progress – but they’ve been in hospital for three months now. They’re very, very weak, and any sudden infection … You just can’t predict.”

Which is why communication, and planning, and involving the family – all those difficult and painful conversations that we naturally shy away from – are so very important.

It could well be, for example, that my father would actually have wanted his death to be prolonged: he certainly clung on to life with a tenacity that startled my sister and me. We will never know, though, because we didn’t talk about any of it.

“It is our responsibility – all of our responsibility – to find the person behind the patient in the bed,” Davis says. “One way or another, we have to have those conversations.”

Complete Article HERE!

Families smuggling lethal drugs into hospitals so loved ones can die: Nitschke

By Julia Medew

Three people smuggled lethal drugs into Australian hospitals last year so their loved ones could secretly take their own lives when nobody was watching, euthanasia campaigner Philip Nitschke claims.

The head of Exit International said all three patients were elderly people with serious illnesses when they took a lethal drug in their hospital beds. They were being cared for at the Royal Prince Alfred and Concord hospitals in Sydney and the Austin hospital in Melbourne.

In each case, a partner or adult child took the lethal drug to them in hospital, Mr Nitschke said. The patients had previously acquired the drug in case they wanted to take their own lives one day.

Mr Nitschke, a former medical practitioner, said the three people took their drug overnight while no hospital staff were watching. The next morning, their deaths were recorded with no suspicion about how they died.

“In each one of those three cases, there have been no questions asked. It’s not surprising because they were very sick. The assumption was that they just died,” he said.

The cases are now being used by Mr Nitschke in his workshops on assisted death. He said while many people fear they will not be able to take their own lives in hospitals or other institutions such as nursing homes, these recent stories show it can be done.

However, he warned that if the relatives were caught smuggling a lethal drug into a hospital, they could be charged with criminal offences including assisting a suicide.

Mr Nitschke recently tore up his medical licence after the Medical Board of Australia demanded he stop discussing suicide if he wanted to keep his medical registration. He has since continued his work with Exit International.

Dr Rodney Syme, of Dying with Dignity Victoria, said he had never heard of families assisting people to die in hospitals in such a fashion. However, he said the reports added to the case for assisted dying laws in Australia. If there were more options for people to end their lives when the time was right for them, he said clandestine suicides in hospitals would not happen.

Margaret Tighe, of Right to Life Australia, said it was appalling that Mr Nitschke was promoting these deaths. She said the hospitals should investigate them and boost their security.

While spokespeople for the hospitals said they did not know anything about the deaths, a spokesman for NSW Health Minister Jillian Skinner said: “Any matter of this nature should be referred to the appropriate agency, the police, and accompanied by details and evidence of the illegal activity.”

A spokesperson for federal Health Minister Sussan Ley said she was “disturbed by any serious breach of accepted or ethical medical standards and this certainly falls into that category”.

“Obviously our department will need to obtain more information from the relevant health offices in both states before we could comment in any detail,” her spokesperson said.

A spokeswoman for Victorian Health Minister Jill Hennessy would not comment on the reported deaths, but said the Victorian government was introducing laws this year to give people more choice about the kind of medical care they want or do not want in the event of future illnesses such as cancer or dementia.

The Australian Medical Association would not comment on the report, but Secretary of the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation, Lee Thomas, said: “It is unfortunate that any person needs to resort to drastic measures to relieve their pain.”

“Overwhelmingly ANMF members support the right to die with dignity and many have been engaged in the dying with dignity movement,” her statement said.

Complete Article HERE!

This doctor helped dying people end their lives with dignity. Then he was diagnosed with cancer.

By Brooke Jarvis

Peter Rasmussen was always able to identify with his patients, particularly in their final moments. But he saw himself especially in a small, businesslike woman with leukemia who came to him in the spring of 2007, not long before he retired. Alice was in her late 50s and lived outside Salem, Oregon, where Rasmussen practiced medical oncology. Like him, she was stubborn and practical and independent. She was not the sort of patient who denied what was happening to her or who scrambled after any possibility of a cure. As Rasmussen saw it, “she had long ago thought about what was important and valuable to her, and she applied that to the fact that she now had acute leukemia.”

From the start, Alice refused chemotherapy, a treatment that would have meant several long hospitalizations with certain suffering, a good chance of death, and a small likelihood of truly helping. As her illness progressed, she also refused hospice care. She wanted to die at home.

Six months after Rasmussen started seeing Alice, he wrote in her chart about his admiration for her and her husband: “Together they are doing a wonderful job not only preparing for her continued worsening and imminent death but also in living a pretty good life in the meantime.” But there were more fevers and bleeding and weakness. In late January, she asked him to write her a prescription for pentobarbital.

Three days later he arrived at her farmhouse with four vials of bitter liquid. Though the law didn’t require it, he liked to bring the drug from the pharmacy himself, right before it was to be used, so that there would be no mistakes.

Over nearly three decades as a physician in Oregon, Rasmussen had developed many strong beliefs about death. The strongest was that patients should have the right to make their own decisions about how to face it. He remembers the scene in Alice’s bedroom as “inspiring, in a sense” — the kind of personal choice that he’d envisioned during the long, lonely years when he’d fought, against the disapproval of nearly everyone he knew and all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, for the right of terminal patients to decide when and how to die.

By the time he retired, Rasmussen had helped dozens of patients end their lives. But he kept thinking about Alice. Her pragmatism mirrored the image he had of how he would face such a diagnosis. But while he had often conjured that image — had faced it every time he walked a dying patient through a list of inadequate options — he also knew better than to fully believe in it. How could you be sure what you would do before the decisions were real?

“You don’t know the answer to that until you actually face it,” he said later — after his own diagnosis had been made, after he knew that he had cancer and that he would soon die. “You can say you do, but you don’t really know.”

The knowledge hid in the back of Rasmussen’s mind — a flitting worry you don’t look at directly — for a few days before he really comprehended it.

He was on his way home from a meeting of the continuing-education group he had joined after his retirement. One of the group’s members had asked him to let the others know that she had been diagnosed with a glioblastoma — a type of brain tumor whose implacable aggression he knew well. A glioblastoma can cause seizures, memory loss, partial paralysis, even personality changes. You can treat the tumor with surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation, but it will always come back, often in more places. The timeline can be uncertain, but the prognosis never is. The median period of survival after diagnosis is seven months.

As Rasmussen drove away from the meeting, his left hand was draped on the wheel of his Tesla. It felt, as it had for several days, oddly numb, as if he’d been holding a vibrating object for too long. He’d ignored the feeling, chalking it up to spending too much time power-washing pinecones off his cedar-shake roof.

Maybe it was what had happened at the meeting, or the clarity of a wandering mind. All at once he focused on the sensation — on how localized it was, on the fact that it hadn’t gone away — and he knew. Something was wrong. “I’ve either got MS,” he thought, “or I’ve got a brain tumor.”

Instead of driving home he went straight to an urgent-care clinic, where a doctor sent him to the E.R., where another doctor gave him an MRI, which showed a tumor. It was, he learned later, a glioblastoma about an inch in diameter. Barring an accident, it would be the thing that killed him, sometime in the suddenly too near future.

Eight days after his MRI, Rasmussen went to the hospital to have part of his skull cut away and his tumor sliced out. He had considered whether having surgery violated his usual advice about not wasting one’s final months seeking painful and unlikely cures, but because his tumor was localized and fairly accessible, he and his surgeon decided that the odds were good enough to try.

The surgery was a success — though Rasmussen lost the use of his left arm, the entire visible tumor was removed, and he was able to leave the next day. Of course, success was only a slower form of failure: He was still going to die. He never let himself, or anyone around him, forget that his reprieve was temporary. “It’s not if I pass away,” he corrected his lawyer, his accountant, his friends. “It’s when I die.”

Before he retired, Rasmussen had often tried to help his patients and their families think of the process of dying as an opportunity, a chance for clarity and forgiveness, for thoughtful, meaningful goodbyes. He hoped to hold on to that belief for himself. When he pictured a good death, the image was simple: calm and peace, without much physical suffering, and his family with him in the house where he’d lived for 18 years with Cindy, his wife; where the kids had grown up; where the windows looked out on his bird feeders and his flowers.

It wasn’t time yet. Five months after the surgery, he stopped chemo and radiation. He began to feel better, stronger, and was even able to use his left hand a little. Still, every time he had a headache or nausea he wondered whether the tumor was growing back. But whenever he started to feel sorry for himself, he’d administer a stern mental shake: “We all die,” he’d tell himself. “It’s never fair to anybody. So buck up.”

Privately, he had no idea whether or not he’d take advantage of Oregon’s assisted suicide law. He consulted a list that he’d kept of his Death With Dignity patients. At first most had been urgent cases: people with all kinds of terminal diseases, who were suffering intensely and wanted to take the drug right away. As time passed, people began coming to him sooner after their diagnoses, before they knew how their diseases would develop. Some only asked questions, and others wanted to have the pentobarbital handy, a just-in-case comfort that made them feel more in control. The majority of his patients never took the medication.

Every death was different, though most had details in common: reminiscing in advance, goodbyes filled with love, family members saying that it was OK to stop struggling. There was the death with the Harley-Davidsons: He’d pulled up to the house and there were motorcycles everywhere, people in leather drinking beer on the lawn, just the party his patient wanted.

Of course, not everyone wanted a party, and he respected that too. Often there were only a few family members, and sometimes it was just him and the patient, alone together at the last. Only once did someone ask to die completely alone, in quiet privacy behind the closed door of a bedroom.

He remembered a woman whose mastectomy had not stopped her breast cancer from metastasizing to her lungs. Her huge family came in for the weekend. They had a picnic on Saturday, went to church on Sunday, and then all the kids and grandkids filed through her bedroom to say goodbye. He waited outside the door until they were done and then he brought her a dose of pentobarbital. She drank it and died. That one stuck with him: “It was about as ideal a death as I possibly could have imagined.”

In July of last year, Rasmussen went in for a new MRI. The scan showed the tumor, the same size and back in the same place it had been the year before. He consulted with his surgeon, who told him that the tumor was once again a good candidate for removal. Rasmussen would most likely lose the use of his left arm altogether, but if all went very well, he would have a one-in-three chance of living to the second anniversary of his diagnosis.

“I’ll leave tomorrow for the trip,” he told Cindy after meeting with the surgeon — meaning a cross-country road trip that he’d been talking about. Cindy was stunned. She hadn’t thought he’d actually go. But he was adamant, and then he was gone.

He drove east through Idaho, Montana, South Dakota, along long, open stretches of quiet road. He brought recorded lectures to keep him company: one about St. Francis, a series on the Higgs boson, and a particularly interesting lecture about gnosticism.

As he drove, he tried to visualize what his life would be like if he underwent surgery or stopped treatment altogether. He imagined losing more of the use of his left side and eventually ending up in hospice, bedbound. That part didn’t bother him so much. He knew it was coming no matter what. But he didn’t like thinking about stopping treatment, not yet. It was too passive, too final. It just made him too sad.

Somewhere around the ninth day of his trip, he had a thought that excited him. “The task of learning to be a hemiparetic person,” of living with paralysis on his left side, could be an adventure, another learning experience. “To take on a challenge is always satisfying,” he explained later. Relief washed over him. He had made a decision.

He wasn’t planning to have the surgery right away, but an hour after arriving home he had a seizure. Four days later he was back in the O.R., and surgeons were once again scooping a tumor from his brain. He woke to find himself paralyzed not just in his arm, but throughout the left side of his body. For days he was noticeably quiet. After three days he moved to a nursing-care facility. The first morning there, he called Cindy to tell her that he’d been very sad the night before. “Did you cry?” she asked.

“No, I didn’t cry,” he replied. “But I was mourning the loss of my independence.”

On Oct. 1, he was admitted to the hospital for a new MRI. The results showed that his tumor had not only grown back but expanded into the middle of his brain. “I want to go home,” he said.

Cindy set up a hospital bed in the living room looking out over his gardens. His stepchildren arrived from New York and Seattle. For four nights Cindy and the kids stayed by his bed, each night thinking it would be the last. Instead, he grew stronger for a time — a month that Cindy calls “one of the most meaningful experiences I’ve ever had and probably will ever have.” He visited with friends and family, watched a slide show of old pictures, listened as music therapists played his favorite songs on the ukulele.

Rasmussen had already started the paperwork for Death With Dignity, but he didn’t want to add the final touch, his own signature. Near the end of October, he was speaking only a few labored words at a time. One day he asked Cindy to help him stand so he could get up to go to the bathroom, something he hadn’t done in weeks. He was so weak and frail that Cindy told him it was impossible. She says she saw the realization happen then: “This is it.”

On Oct. 29, Rasmussen signed the paperwork and his siblings flew in from Wisconsin, Illinois, and North Carolina. He planned to take the drug the next week, after what Cindy calls “a memorial service while he was still alive.” Sixteen people gathered around Rasmussen; one by one they told him what he had meant to them and what they would remember about him.

He was alert but not talking much on the morning of Nov. 3. His family intertwined their arms in a circle around him and put piano music on the stereo. He raised the cup of secobarbital mixed with juice — papaya, orange, and mango, his favorite — and drank it down. His eyes closed. Cindy, sobbing, realized how similar the scene was to what he used to describe when he came home from someone else’s death. “It was awful,” she says. “But at the same time, I was glad that he was able to end his life on his terms.”

Half an hour later, he quietly stopped breathing.

Wellness Corner January 2016 – California’s End of Life Options Act

by Veronica Jordan, MD

Calfornia’s End of Life Options Act

Imagine you are sick, really sick. Actually, you are dying. Things feel out of your control. You are in pain, or extremely weak. Perhaps you feel too ill to enjoy the things you love to do. You want to know your options – you want to know what the rest of your life will look like, but you also want to have some control over your death. Ideally, you’d like to die with dignity.

On Monday, October 5, 2015, California became the fifth state in the nation to legally protect a patient’s right to have a physician assist him/her in dying. The End of Life Options Act, modelled closely after Oregon’s 1997 Death with Dignity Act (DWDA), allows California physicians to provide life-ending prescriptions to patients diagnosed with a terminal illness.

As a primary care physician, it’s important that I understand the details of this new law, and as we all are potential patients, it may also be of interest to you. I want to start with a few interesting facts I found in reviewing Oregon’s 16 years of experience.

1) The number of Oregonians using physician assisted suicide has increased steadily since 1998, though these deaths are still a very small percentage of Oregon deaths. In 1998, there were 16 patients who died with assistance; in 2013, there were 73. A total of 1,173 patients have received prescriptions, and 752 died with assistance.

2) Most Oregonians who use physician-assisted suicide are over age 65 (in 2013, the range was 42-96 years).

3) Most have cancer (65% in 2013, 80% in 2012). The second most common diagnosis is chronic lower respiratory disease (e.g. chronic bronchitis and emphysema).

3) 97% died at home.

4) 85% were enrolled in hospice care at the time of death.

5) The three most frequently mentioned end-of-life concerns are: loss of autonomy (93%), decreasing ability to participate in activities that made life enjoyable (88%), and loss of dignity (73%).

To whom does the CA law apply?

Per the new law, patients eligible to receive physician assistance must 1) be at least 18 years of age, 2) be residents of California, 3) be considered mentally competent, and 4) be diagnosed with a terminal illness and six months or less to live.

Patients must also be mentally and physically able to self-administer the aid-in-dying drug. Yes, each patient must be physically well enough to take the medication him/herself.

If a patient has a diagnosed “mental disorder”, the physician must refer him/her to a mental health specialist (psychologist or psychiatrist), who is responsible for determining the individual’s capacity to make medical decisions.

Which physicians can assist patients?

The process is legally mandated to be facilitated by a physician with “primary responsibility for the health care and treatment of an individual’s terminal disease”. This will include primary care physicians (i.e internists and family medicine physicians like myself) as well as specialists (e.g cancer doctors, heart doctors). In Oregon, by one measure, 64% of prescriptions were provided by primary care physicians.

How does an eligible patient actually get aid-in-dying?

First, a person who meets the above criteria must submit to their physician an oral request two times, at least 15 days apart. These requests must be done in person, face to face (not on email, telephone, etc) and documented by the physician. The physician must consult with patients in private to prevent coercion from family members.<

Second, a “consulting” physician must confirm the patient’s prognosis through a physical exam and review of medical record.

Third, the patient must submit a written request. The signed request must be witnessed by two people, who must attest the person (a) has capacity; (b) is acting voluntarily; (c) is not being coerced to make or sign the request. Only one witness can be related (blood, marriage, partnership, financial benefit), and only one can work at the healthcare facility where the person is getting treatment.

The patient must communicate with the physician to confirm 48 hours before taking the medications, and he/she must take the medications himself/herself.

The law will not take effect until 90 days after Congress adjourns the special session on healthcare.

Complete Article HERE!

2015 is the year America started having a sane conversation about death

The American health care debate used to get bogged down in fights over rationing and “pulling the plug on grandma.” Not anymore.

by Sarah Kliff

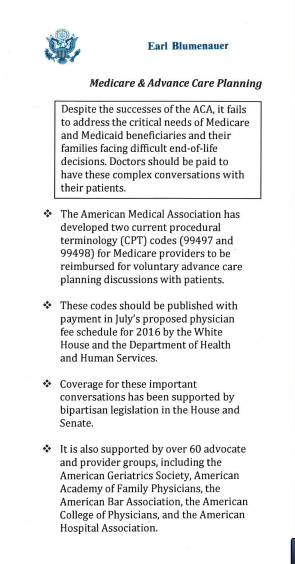

Earl Blumenauer had become accustomed to losing.

During the health reform debate, the Oregon congressman pushed a provision that would reimburse doctors for helping Medicare patients draw up advance care directives.

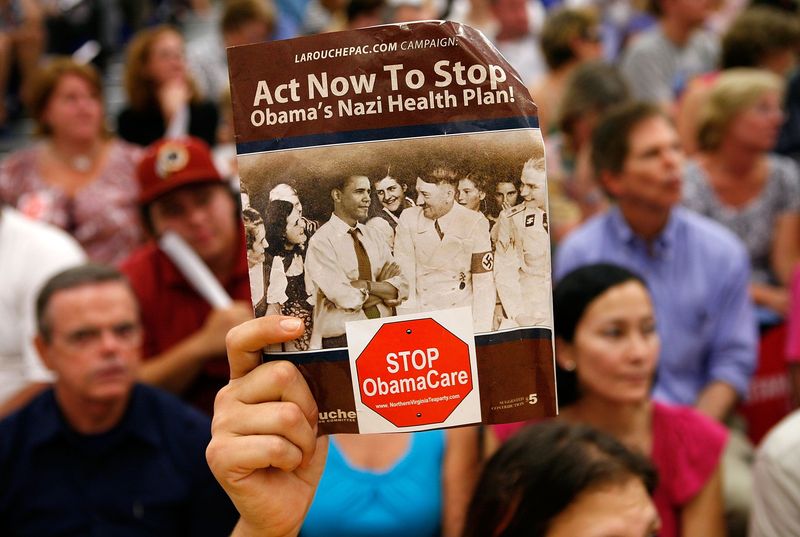

Blumenauer’s proposal quickly became the most politically toxic section of a law rife with contested projects and programs. It’s the part of Obamacare that Sarah Palin termed “death panels.” In August 2009, amidst ugly skirmishes at angry town halls, legislators relented. They left the end-of-life planning provision on the cutting-room floor.

“It was very difficult, in part because of the lingering death panel cloud”

But Blumenauer was undeterred. He quickly began lobbying the Obama administration to create the advance care benefit through regulations that Congress wouldn’t have to approve.

“It was very difficult, in part because of the lingering death panel cloud,” Blumenauer told me in a recent interview.

Since 2009, Blumenauer has doggedly — and unsuccessfully — badgered any Obama administration member who might listen to his cause. But the White House, for five years, wouldn’t budge. Every year, it would put out the list of services Medicare would reimburse. And every year, advance care planning would not be on it.

Blumenauer recalled once attending a picnic at the White House — and pestering administration officials to take small cards he’d had printed up to summarize his case.

“At this year’s White House picnic, around the Fourth of July, there was some indications it could go our way,” he says.

On November 2, Blumenauer finally won: The White House finalized rules that will allow doctors to be paid for every discussion they have with patients about creating an advance directive.

The United States has — quietly and with little fanfare — begun to do something quite remarkable. We’ve started to have a more sane conversation about death, something that just this spring, as I wrote in a lengthy essay, seemed near impossible. That has allowed for significant policy changes that will, starting in 2016, begin to revamp the way Americans plan for the inevitable.

I’ve spent much of the past month asking legislators, doctors, government officials, and advocates about how that happened. They say health care became a much less heated topic. Doctors and patients, meanwhile, began to take a bigger leadership role. And the White House, cognizant of Obama nearing the end of its term, appeared to see a last moment for action — and decided to seize it.

“As a country, we’re more willing to have a conversation around the end of life,” says Kim Callinan, chief program officer for the end-of-life advocacy group Compassion and Choices.

Medicare spends billions on end-of-life care. But patients aren’t getting the care they want.

Dying in America is expensive. The 6 percent of Medicare patients who die each year typically account for 27 to 30 percent of the program’s annual health care spending. Medicare spent an average of $33,500 for beneficiaries who died in 2011 — four times the amount it spent on the seniors who lived.

Health care providers often make heroic efforts to save patients’ lives in their final days and weeks. The average Medicare patient who dies from cancer spends 5.1 days of his or her last month of life in the hospital. A quarter of these cancer patients are admitted to the intensive care unit over the same time period.

But surveys of patients with terminal disease suggest this isn’t what they actually want. One survey of 126 patients facing near death found they had five priorities at the end of life — and prolonging life was not actually among them.

Patients told researchers they wanted their pain controlled, a sense of control over their care, their burdens relieved, and time to strengthen relationships with loved ones. They also specifically did not want the “inappropriate prolongation of dying.”

A 2012 paper found that cancer patients who have less intensive care at the end of life — who have fewer hospitalizations and intensive care unit visits in their last week of life — report the best quality of life at the time of death.

In Washington, something so costly that leads to worse patient outcomes would be, in other public health programs, a no-brainer. But with end-of-life care, the opposite tends to be true: We can’t talk about the cost of dying because it sounds like a discussion about rationing. Taking cost into account feels callous and inappropriate in the context of death. For years now, that’s made end-of-life care an unapproachable topic on Capitol Hill.

That the already-polarizing health reform law included policy changes for end-of-life care certainly did not help matters.

“This was toxic for a while because of the gross mischaracterization of what we wanted to do,” says Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA), who has worked on end-of-life care legislation.

Warner, like many other legislators who work on the issue, had his own personal story of attempting to care a loved one — in his case, his mother, as her Alzheimer’s worsened.

“I was someone who was relatively informed; I was the governor of Virginia,” he says. “We knew something was coming, but we never had the conversation within our family that we needed to. This is an issue that has touched every family, and touched all the ups and downs of the health care debate.”

How 2015 changed the way America talks about death

The first two attempts to pay doctors to talk about death started in Washington. And both were abject failures.

The first attempt touched off the “death panel” outcry during the summer of 2009.

The second came in the winter of 2010, when the Obama administration tried quietly slipping the new benefit into regulations that outline how much Medicare doctors get paid for various procedures. That approach seemed to work — until an eagle-eyed New York Times reporter noticed the regulatory bombshell and wrote a story for the paper’s front page. Within days, the Obama administration retreated.

“We were, to put it mildly, disappointed when the administration changed course at the end of 2010,” says Blumenauer. “Any poor soul who happened to be the secretary of Health and Human Services or high ranking at the Center for Medicare Services has heard from me about it.”

Any federal proposal to change the way Americans die was met with immediate skepticism and framed as a government takeover of health care.

This last successful attempt didn’t start in the White House. It didn’t even begin in Washington. It began far outside the Beltway, at the 2012 meeting of the Illinois State Medical Society.

That’s where two doctors from the DuPage Medical Society — which covers the county just west of Chicago — brought to the floor a resolution to ask the American Medical Society to create a billing code for advance care planning discussions. Somewhat confusingly, the AMA creates all the billing codes that Medicare uses, while the government decides how much to pay for each code.

“This was the voice of doctors saying, ‘We want this,'” says Scott Cooper, executive director of the Illinois Medical Society. “Because it came from physicians and was based on clinical experience, and not some policy wonk who had some idea in Washington. It’s an easier sell when you have the voice of the medical community.”

The resolution passed — and a handful of Illinois State Medical Society members flew to an AMA meeting in 2013 to deliver their request in person. They were successful, and the AMA created two codes.

“It’s not every day you just create a new procedure for Medicare,” says Cooper. “We’d never done it before. But this was relatively seamless and easy. It didn’t face any pushback.”

After that 2013 meeting, the billing codes existed — but Medicare never attached any money to them. If a doctor had tried to bill for an end-of-life planning discussion, no reimbursement would show up. Advocates pushed delicately on the issue, knowing that Medicare was a massive agency they had to work with on countless other issues.

“It’s not every day you just create a new procedure for Medicare”

“You don’t want to be put in this awkward position of pushing too hard against an administration or executive branch that has largely been doing many positive things,” says Peter Hollmann, a board member of the American Geriatric Society and a practicing physician in Rhode Island.

Medicare sat on the codes for two years. But in early 2015, rumors started to ripple through Washington’s health policy circles: This would be the year that Medicare started paying for end-of-life discussions.

The timing made sense: This was, arguably, the last moment the Obama administration had to create the benefit. If the administration waited until 2016, it would be making the change mere days before the presidential election — a risky time for any policy change. Late 2015 appeared to be the Obama administration’s last shot.

“People felt this was the last chance to do this,” Hollmann says. “No one knows what can happen in an election year, with the potential for shenanigans.”

On July 8, Medicare published draft plans to pay doctors to talk about death (about $80 for the first 30 minutes, and another $75 for an additional half-hour). The agency invited comments, which came back near universally positive.

“I am a healthcare professional in palliative care and advance care planning is critical to patients and their loved ones,” one doctor from California wrote in.

“Patients and families deserve to have realistic information provided by their doctors, rather than relying on their assumptions often fed by the popular media about what ‘life support’ and ‘rehabilitation’ can actually look like,” another in Oregon commented.

“Please add the codes below,” another Tennessee doctor requested, “so end-of-life suffering can be minimized.”

There was no outcry, and no doctors objecting to the new Medicare benefit. On October 30, Medicare made the decision official: Beginning in January 2016, it would pay doctors to talk about death.

“It’s a terrible, terrible way to die”

Much like in Washington, bills that changed end-of-life policy never had much luck in California before.

Advocates there, however, wanted to go much further: They had pushed legislation that would allow doctors to prescribe lethal medication to terminally ill patients — in other words, physician-assisted suicide.

But efforts failed in 2005 and 2007, as the California legislature rejected the proposal. Only small, decidedly liberal states like Vermont and Oregon seemed willing to pass those laws.

That all changed with Brittany Maynard, a 29-year-old who died in late 2014 from a rare brain cancer called glioblastoma multiforme. It’s a fatal disease that typically causes massive cognitive decline in the last months of lives. Patients can become unable to remember their own last names or to distinguish between a trash can and a toilet.

“My glioblastoma is going to kill me, and that’s out of my control,” Maynard told Peopleat the time. “I’ve discussed with many experts how I would die from it, and it’s a terrible, terrible way to die.”

Maynard looked at that future and made a firm decision against. She moved to neighboring Oregon, which allows doctors to prescribe lethal medications to terminally ill patients like her. Maynard used that law to take her own life on October 30, 2014.

Before her death, Maynard also recorded a series of videos imploring California’s legislature to pass a similar law — which would allow other Californians to choose the same death without moving hundreds of miles north. She recorded testimony that was presented to the legislature in March 2015 — five months after her death.

Compassion and Changes ran its largest-ever campaign for a state bill, putting a half-dozen organizers on the ground throughout the state. It had a watershed moment when the California Medical Association, which had opposed previous aid-in-dying bills, agreed not to take a stance on the new legislation.

Maynard’s illness caused the group to “start taking a look at our historical positions,” California Medical Association spokesperson Molly Weedn told me over email. “The decision was made to remove any policy that we had on the books that outright opposed aid in dying. We wanted to ensure that it was a decision made between a physician and their patient and determined around individual instances.

On October 5 — 340 days after Maynard’s death — California Gov. Jerry Brown signed Assembly Bill 12 into law. In one fell swoop, Brown tripled the number of Americans who live in states where doctors can prescribe lethal medications to patients whom they expect to live six or fewer months. In his signing statement, he cited the letters he’d read from Brittany Maynard’s family.

“I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain,” Brown wrote. “I am certain, however, that it would be a comfort to be able to consider the options afforded by that bill. And I won’t deny that right to others.”

A saner approach to death in 2016?

In some ways, the 2015 changes to end-of-life policy in America were large. Medicare didn’t pay doctors to talk about death. Now it does. This year, 13.7 million people live in places where it’s legal for physicians to help terminally ill patients end their lives. Next year, that number will jump to 52.2 million people.

But in other ways, these changes are still quite small. Data from Oregon suggests that the number of people who use the California law, for example, will be relatively small. And advocates for end-of-life care planning see much work to do when it comes to ensuring that Americans’ preferences for care at the end of life are met.

Lee Goldberg directs Pew Charitable Trusts’ improving end-of-life care project, and he sees the new Medicare benefit as a first step rather than an end goal. There’s work to be done to ensure that doctors are equipped to have these conversations — and that patient preferences that do get recorded are easily accessible when patients have emergency situations.

“The odds are no better than chance right now, so that’s a big challenge, making sure this patient data is available when it’s needed,” he says.

Goldberg and others see 2015 as something akin to a proof of concept: proof that the American political system and state governments can pursue changes to end-of-life care policy without getting shouted down about death panels and rationing. This doesn’t guarantee future change but at least allows for the possibility. Because in 2015, it wasn’t impossible for Blumenauer to get the administration to pay attention to his pocket cards.

“It does wear you down sometimes,” he says of sticking with the issue for so long and seeing so little progress until now. “How many times do you answer the same questions on something that seems so compelling, and every year have the answer be no? But every year the case became stronger, and that’s more difficult to say no to.”

Complete Article HERE!

WHAT’S THE BEST WAY TO DIE?

Given hypothetical, anything-goes permission to choose from a creepy, unlimited vending machine of endings, what would you select? Should you have the right to choose?

BY ROBYN K. COGGINS

After a particularly gruesome news story — ISIS beheadings, a multicar pileup, a family burnt in their beds during a house fire — I usually get to wondering whether that particular tragic end would be the worst way to go. The surprise, the pain, the fear of impending darkness.

But lately, I’ve been thinking that it’s the opposite question that begs to be asked: what’s the best way to die? Given hypothetical, anything-goes permission to choose from a creepy, unlimited vending machine of endings, what would you select?

If it helps, put yourself in that mindset that comes after a few glasses of wine with friends — your pal asks something dreamy, like where in the whole world you’d love to travel, or, if you could sleep with any celebrity, who would it be? Except this answer is even more personal.

There are lots of ways to look at the query. Would I want to know when I’m going to die, or be taken by surprise? (I mean, as surprising as such an inevitable event can be.) Would I want to be cognizant, so I can really experience dying as a process? Or might it be better to drowse my way through it?

Many surveys suggest that about three-quarters of Americans want to die at home, though the reality is that most Americans, upwards of 68 percent, will die in a hospital or other medicalized environment. Many also say they want to die in bed, but consider what that actually means: just lying there while your heart ticks away, your lungs heave to a stop. Lying around for too long also gets rather uncomfortable — as anyone who’s spent a lazy weekend in bed can tell you — and this raises a further question: should we expect comfort as we exit this life?

Sometimes I think getting sniped while walking down the street is the best way to go. Short, sweet, surprising; no worries, no time for pain. Sure, it’d be traumatic as hell for the people nearby, but who knows — your death might spark a social movement, a yearlong news story that launches media, legal, and criminal justice careers. What a death! It might mean something. Does that matter to you — that your death helps or otherwise changes other people’s lives? If there’s not a point to your death, you might wonder, was there a point to your life?

These are heavy questions — ahem, vital, ones — that don’t seem to come up very often.

I got curious about how other people would answer this question, so I started asking colleagues and friends for their ideal death scenarios (yes, I’m a blast at parties). I heard a wide variety of answers. Skydiving while high on heroin for the second time (because you want to have fun the first time, according to a colleague). Drowning, because he’d heard it was fairly peaceful once the panic clears. Storming a castle and felling enemies with a sword to save a woman, who he then has appreciative sex with, just as he’s taking his dying breaths. (That poor gal!) An ex-boyfriend of mine used to say that the first time he lost bowel control, he’d drive to the Grand Canyon and jump off.

My own non-serious answer is to be tickled to death, sheerly for the punniness of it.

Anecdotally, young men were more fancy-free about their answers, while the older folks and women I spoke with gave more measured answers or sat quietly. Wait, what did you ask? I’d repeat the question. A pause. Hmm.

One old standby came up quite a lot: dying of old age in my bed, surrounded by family. The hospital nurses I asked had a twist on that trope: in bed, surrounded by family, and dying of kidney failure. Among nurses, there was consensus that this is the best way to go if you’re near death and in intensive care — you just fade out and pass, one ICU nurse told me. In the medical community, there’s debate about how calm death by kidney failure actually is, but really, who can you ask?

These answers are all interesting, but my nurse friend got me wondering about people who deal with death on the regular — what do they think about the best death? Do they think about it? Surely hospice workers, physicians, oncologists, “right-to-die” advocates, cancer-cell biologists, bioethicists, and the like have a special view on dying. What might their more-informed criteria be for my “best death” query?

I started with a concept that I think most can agree with — an ideal death should be painless.

***

Turns out, a painless death is a pretty American way to think about dying.

Jim Cleary, a physician in Madison, Wisconsin, specializes in palliative care, cancer-related pain relief, and discussing difficult diagnoses with patients. “Eighty percent of the world’s population lacks access to opioids,” he tells me. That includes morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone, and many of the other drugs used to soothe patients in the United States. Cleary is director of the World Health Organization’s pain and policy studies group, which is working to get these relief drugs to other nations to help those in need — burn and trauma victims, cancer patients, and women giving birth.

In his work with American cancer patients, he’s careful not to suggest that dying will be comfortable. “I can’t promise ‘pain-free,’” he says. What he can promise is that he’ll try his best to help patients end their lives as they wish. “Listen to your patients,” he tells his colleagues, “they have the answers.”

Cleary says you can lump the different ways we die into categories. The first is the sudden death. “That’s not going to be a reality for most of us,” he’s quick to point out. The other category is the long death, which is what most of us will likely experience. “The reality is death from cancer,” says Cleary, “where you actually know it’s going to happen, and you can say goodbye.”

According to the American Cancer Society, a man’s risk of dying from cancer is 1 in 4, and a woman’s 1 in 5. (It’s important to note that those numbers are just for dying from one of the many types of cancer, from bladder to brain, prostate to ovaries. The odds that a man will develop cancer are 1 in 2; for women, 1 in 3. Reality, indeed.) In long-death cases, most care does not extend life so much as extend the dying process, a fact noted by many end-of-life experts, from surgeon and author Atul Gawande to hospice patients.

Cleary thinks the idea of a “best” death or even a “good” death is a little misleading, as if it’s a competition or something one can fail at. He prefers the term “healthy dying,” which isn’t as oxymoronic as it sounds. To him, healthy dying means that death is “well-prepared for, it’s expected, and other people know about it.”

“We as a society have to do much, much more on accepting death as a normal part of living,” he says. “So rather than even talking about what’s ‘the best way to die,’ how do we normalize dying?” In a country where funeral parlors handle our dead and corpses no longer rest for days in our own parlors at home, we’re rather removed from the whole ordeal.

Still, I press Dr. Cleary to answer the question at hand: How would he choose to die? “Would it be sudden death walking along a beach in Florida?” he ventures, then quickly reconsiders. “But if your family doesn’t know you’re dead — dad goes for a walk or run and doesn’t come back — is that good for them? It may be good for me, but it may not be good for them.”

***

In many American hospitals, you’ll find representatives from No One Dies Alone (NODA), a nonprofit volunteer organization formed in 2002 by a nurse named Sandra Clark. NODA’s founding principle is that no one is born alone, and no one should die alone, either.

NODA volunteers work in groups of nine. Each carries a pager 24 hours a day during their assigned shifts, so that one of them is always available to attend a death. Usually, a nurse makes the phone call summoning NODA volunteers. The vast majority of people who NODA visits are comatose. But that makes no difference, the principle abides; comatose or not, it’s still important for someone — anyone — to be present.

Anne Gordon, NODA’s current program director, has helped hospitals around the country start the program in their facilities. She has a worldly perspective similar to Cleary’s, and different from the expectations that most Americans have on the topic of death.

“Dying is a process, not [just] the last breath,” says Gordon. If you’re a hospital patient in the process of dying, there’s a specific protocol to qualify for NODA services. You need to be actively dying — estimated to pass in the next day or so. (“Seasoned nurses can tell,” Gordon says, which is why they’re often the ones to page the NODA volunteers.) You must have reached a point where you will not receive any further interventions — that means comfort care only, with a required “do not resuscitate” order. And you must be without family or friends who can keep you company as you pass away.

Nobody? How does it happen that a person has nobody to visit when they die?

“Sometimes a person’s outlived everyone, or they’re estranged,” Gordon explains. Maybe they do have family, but for whatever reason, the loved ones needed to leave, or live far away, or just cannot bear to be present. Some of the patients are homeless and, just as in their healthier days, have no one to comfort them. Whatever the reason, NODA will be there.

As Gordon sees it, death is an act of meaning, and the process — what she calls “the human family coming together” — is an act of intentionality and love. “I find the whole process to be so compelling,” she says. “It’s our shared experience — a key transition we all share.”

Gordon, a Baby Boomer, sees her work and the recent public interest in end-of-life issues as a byproduct of her generation aging — an extension of the consciousness-raising of the 1960s and “one of the good echoes” from that era, she quips. “As we get closer to death, we like to talk about these things.”

There are “death cafes,” informal coffee hours where friends and strangers get together, eat cake, and talk about dying. There are high-demand conferences where people share their personal experiences of loss and grief. There are bestselling books about coming to terms with your own mortality and how to prepare for death — spiritually, familially, and financially. Even Costco, the bulk-retail giant, sells coffins alongside its low-price tire changes and discount cruises. It’s mostly just static noise, though. Death is never fully discussed, only hinted at from the margins.

Gordon believes that now — with Baby Boomers entering retirement, many losing their parents, and many more coming to grips with their own mortality — is the moment to talk through these issues as a culture, to discuss the process of death in specific terms, beyond the anecdotal and platitudinal. “When death is a daily concept,” as it might be in Bhutan, she offers, “it’s not as terrifying. What matters is quality of life.”

When I ask Gordon how she’d like to die, she demurs. “I have no answer. I figure it’ll be what’s appropriate for me.”

***

Pamela Edgar is an end-of-life doula and drama therapist in Brooklyn, New York. Similar to how birth doulas help pregnant women bring new life to the world, end-of-life doulas help people on their way out.

Edgar grew up with a mom who worked in nursing homes, and young Pamela sometimes tagged along, visiting people at different stages in their lives, including the final ones. As she grew older, Edgar got especially interested in those last months: “What is the kind of relationship that you can have with someone when it might be one of their last new relationships? What can that be like?” she wondered.

Edgar has worked in nursing home dementia units and other late-life facilities for the past eight years. After working in a Veterans Administration hospital during an internship as a creative arts therapist, she requested to go to the hospice unit. (“Nobody ever asks to do that!” she remembers her supervisor replying.) For the past three years, she’s been an end-of-life counselor with Compassion & Choices. The organization is primarily known for advocating right-to-die legislation at the state level, but it also helps anybody seeking assistance to “plan for and achieve a good death.”

“As a drama therapist,” Edgar says softly, “I look a lot at roles that people play in their life, and one of the things that I really see — and this is a little bit related to a good way to die — I see that for a lot of us, a lot of our lives are spent doing. What can we do for other people, how we define ourselves by these roles that are really about what we can do, or what we have. And as people get older, of course, that role system gets smaller, and often people can’t do all the things they used to do. I think it’s really an interesting moment for people then: What is their identity, and who are they now?”

For many, dying becomes about control and autonomy, she says. “Here are the things I still can do and what I can still control are really important for some people.”

Others get spiritual. Edgar shares the example of a patient in his 70s who’d been diagnosed with ALS and lost the ability to do many of the things he loved. “He decided that he was ready, and he and his wife kind of describe it that ‘his spirit had outgrown his body.’ He was on hospice care and he chose to stop eating and drinking, and the wife had a lot of support, and hospice was really excellent and supportive of them. It was a very peaceful passing for him.”

Peaceful. Especially given the circumstances of a degenerative illness, “peaceful” seems like an indispensable criterion for the “best” death.

Edgar has been particularly affected by seeing choice taken away from patients. Many of the people she worked with early in her career wanted to go home but, because of what she calls the country’s “medical model” of dying, never were able to. After helping hundreds of people with their deaths — filing wills, deciding on final treatments, aiding loved ones with the transition — she’s developed an idea of a good death that’s based on her background in psychology. You’ve heard it before: letting go.

“Ultimately, we are going into an unknown,” Edgar says. “Even when people think or have ideas about what’s next, truth is, we don’t have proof. So there is that sense of going into an unknown and do people feel ready — body, mind, and spirit? Are they really ready to go?”

Sometimes, Edgar says, the body and mind are ready, but the person isn’t emotionally there yet. Or vice versa — the person feels spiritually ready, but their body’s still holding on.

“My personal answer for the best way to die is being ready, like being physically, emotionally, spiritually ready to go.”

Before we end our conversation, she stresses a point to me: “Life and death are not opposites,” she says. “We haven’t figured out how to stop either. They’re partners.”

***

In the autumn of 2014, the story of Brittany Maynard incited conversations on this topic in average American living rooms. Maynard, a 29-year-old newlywed, was diagnosed with an incurable brain cancer that gave her seizures, double vision, headaches, and other terrible symptoms that inevitably would intensify until her almost surely agonizing death.

As she looked at that future, Maynard decided that she wanted to end her life on her own terms with the help of legal medication. Unfortunately, she lived in California, which didn’t allow doctors to write life-ending prescriptions. So Maynard, her husband, and her mother packed up and moved to Oregon, where the right to die is legally recognized.

Through the ordeal, Maynard partnered with Compassion & Choices to spread the word about her journey for a good death. Her story appeared on the cover of People magazine, was featured on CNN, the Meredith Vieira Show, in USA Today, in the op-ed pages of the New York Times — you name it. Such a young woman facing such a terrible fate: it’s compelling, even wrenching, and hard to turn away from.

Disregard your personal beliefs on the morality of this situation for a moment, and think about what you would do in the face of an agonizing terminal diagnosis. Would you seek medical care until the very last breath, demanding chemo from your deathbed? Or would you prefer to go without, letting the disease take its natural course? Which path do you fear the most?

David Grube is an Oregon family doctor who, in his own words, has “delivered babies and sung at people’s funerals.” He wants to die “feeling perfectly well, and just not wake up.” Over his 35-year career, he has prescribed life-ending drugs to about 30 patients (though “aid in dying,” as it’s often called, only became legal in Oregon — and for the first in time the United States — in 1994). He did not prescribe Maynard’s medication, but he did talk to me about the process of aiding in a patient’s death.

Grube, who is the medical director for Compassion & Choices, says that though many people ask for the drugs, few end up using them. The prescriptions require a psychological evaluation, sign-off from two different physicians, and a 15-day waiting period before they’re available. The fatal dose will be a barbiturate like pentobarbital, a sedative that’s also used in animal euthanasia — it’s the same drug as the “sleeping pill” that killed Marilyn Monroe, Grube notes — or secobarbital, a bitter anesthetic and sleep aid. Someone like Brittany Maynard would likely stir the drug into a glass of juice, drink it, then await its effects.

In her final message to the public, Maynard wrote, “The world is a beautiful place, travel has been my greatest teacher, my close friends and folks are the greatest givers. I even have a ring of support around my bed as I type. … Goodbye world. Spread good energy. Pay it forward!” Her husband, Dan Diaz, said that as she took the medication, “The mood in the house was very peaceful, very loving.” Within five minutes, she fell asleep. Then she died.

Grube says that’s usually how it goes with these cases: within an hour or two, the person stops breathing and experiences “a peaceful, simple death.” On the rare occasion when the patient takes the medication with a glass of milk or with a large dose of anticonstipation medication (vanity doesn’t automatically disappear with terminal illness), they will sometimes wake up. But when taken as prescribed, most people who choose to end their life this way will, like Maynard, pass with tranquility. It is, in a word, peaceful.

Another term for Maynard’s act is “physician-assisted suicide,” but Grube rejects that concept wholeheartedly. “They don’t want to die!” he says. “‘Suicide’ is such a harmful word … and words are scalpels; they can be healing, kind, or destructive.” Some of Grube’s allies prefer the term “physician-assisted dying,” while others talk about the “right to die.” Compassion & Choices has settled on its own values-based language to discuss cases like Brittany Maynard: “death with dignity.” Partly due to Maynard’s activism, the California legislature and Governor Jerry Brown passed the “End of Life Option Act” this October, just before the one-year anniversary of her death.

Grube says most people who ask for these prescriptions are educated, motivated, and confident. What they want, he explains, is to determine the timing of their imminent death.

Control. When a disease is controlling your body and mind, when you’ve lost pleasure in the things you once loved, when you’re in pain, when you’re suffering and you fear burdening those around you, when there’s nothing more to do but wait for death, having the power to take — or not take — life-ending drugs can be a supreme comfort. But it’s a fine line of morality.

As a philosopher and bioethicist at Vanderbilt University, John Lachs considers these situations all the time. His mother, Magda, lived to 103, but given her ever-increasing collection of age-related illnesses, he wrote in Contemporary Debates in Bioethics, “living longer seemed to her utterly pointless: the pain, the indignity and the growing communicative isolation overshadowed her native optimism and the joy she had always taken in being alive. She decided that she had had enough and she was ready to die.”

Magda stockpiled prescriptions, ready to overdose on them, but lost them in a move, according to her son. She tried to die by abstaining from food and drink, but, as Lachs put it, “there was enough love of life left in her to make this a regimen she could not sustain.”

Is it okay to help someone else die? Lachs argues that “doctors should help us through every stage of life,” including the final one. Furthermore, exercising freedom — in this case, the freedom of choice to end one’s life — is not the same as following moral rules. “We have the right to terminate our lives even if it is wrong to do so,” Lachs says — with an important caveat. “Healthy young adults who propose to kill themselves cannot demand aid from others. … The situation is altogether different with suicide that is justifiable.”

To Lachs, context is of the utmost importance. “We don’t want people to choose death over life,” he tells me. But when the end is near anyway, and the person is suffering, what’s the argument against it?

- The philosopher has developed a set of five standards for the ideal death:

- It must be after a person has exhausted his purpose; there’s got to be nothing more for him to truly do.

- Corresponding to the loss of purpose is a lessening of energy — mental and physical.

- The person’s affairs should be in order — paperwork, wills, goodbyes, all of it.

- The person should feel he’s leaving something good behind — “I didn’t live for naught.”

- The death should be quick and painless.

Lachs has seen and heard of people who are near death but linger on. “It’s so much better when the other conditions are met and they just pass on,” Lachs says. “Ideally, life is such that it gives you a chance to get ready for death.

“Nobody has ever survived life. The bet is going to be lost. All of life is uncertain. We think it’s not, and contingency is the name of the game. But ultimately, we’re going to have to come to terms with the end of it.”

Magda, Lachs’ mother, finally did pass in the “subterfuge” way that hospice workers sometimes quietly administer: a nurse offered a morphine solution that depressed Magda’s lung function and finally accelerated her death.

What’s the best way to die? It’s a question that Lachs has spent time considering. His favorite answer comes from a medical colleague of his, but it’s an old yarn: being shot to death at 90 years old by an irate husband while biking away from sleeping with the gun-toting man’s wife.

Barring that, Lachs says, he’d like to die having met his own criteria — quickly, of a heart attack.

***

One of the last people I posed my question to was Doris Benbrook, director of research in gynecologic oncology at the University of Oklahoma. Her specialty is much different from the health care staff I’d spoken to previously — she studies cancer on the cellular level, particularly apoptosis, or programmed cell death. Does the microscopic level of dying give us any other ways to think about the best way to go?

In its most basic sense, a cancer cell over-multiplies and begins causing bodily trouble. “At the organ and tissue level, it eats away at vital organs. It grows, duplicates, divides.” That clogs up organs, cascades into other systems, and makes its body croak. How utterly unfair of something so tiny. Some cancers you barely feel, like the notoriously silent ovarian cancer, while others, like bone cancer, cause immense, deep pain.

Benbrook’s work with apoptosis aims to switch off that growth, to figure out how to flip the cell’s existing kill-switch so it can’t wreak such havoc. Years from now, she hopes, doctors could even use this mechanism as a cancer-prevention method.

Interestingly enough, CPR and other familiar cardiovascular attempts to keep people alive take the opposite tack: “They want to prevent cell death,” Benbrook notes. So there are many different ways to think about what the end of a cell means for the end of the human. But cells die constantly, and a few cells dying here and there don’t kill a person. Even though our cells die with us, she stressed that the microscopic level isn’t the right place to look when considering dying.

Her personal answer to the best way to die, however, was my favorite, if only for its imagery.

“I would like to die by freezing to death,” she says. “Because from what I understand of the process, it’s that you eventually just go numb and don’t feel anything. I have experienced extreme pain. I don’t ever want to do it again. I would like to go peacefully.”

Interesting. But it’s where she’d like to freeze to death that moved me.

“I would think that if I were to just sit on an iceberg floating up in the Arctic Ocean, that it would be a peaceful death. I could look up at the stars, I could think about life, and it could be a good experience.”

The frozen night air blowing over your body. The dead quiet of nature interrupted only by laps of the ocean and the occasional fish flopping out of the water. The icy sensation of your tears freezing as you look up at the Great Bear constellation for the last time. That really doesn’t seem like such a bad way to go.

But Benbrook and I come quickly back to land. “Of course I would like to have my family surrounding me, and the chances that I’m going to go sit up on an iceberg in the Arctic Ocean to die — that is not likely.” She laughs. “I’d probably be laying in a bed surrounded by loved ones. My goal would be to go peacefully.” Back to the beginning.

***

So I turn to you, brave and patient reader: from the absurd to the probable, how would you like to die? Allow yourself to think about it, in as far as you’re ready to do so. Do you want a breathing tube snaked down your throat if it becomes necessary? Do you want to be fed if you can’t do it yourself? Would you mind dying in a hospital? You can even get down to ambient details — do you want punk music blasting, a warm room, someone rubbing your swollen feet?

Whatever you wish, however deeply you’re willing to think about it, the key is to share your ideas about a good death. Talk to your family, write down what you want, and keep it somewhere they know about. Ask people about it at parties. As anyone who’s made a “pull the plug” decision can tell you, any guidance you leave will be helpful if you can’t speak for yourself on your last day.

This is your last possible decision, after all — better make it a good one.

Complete Article HERE!

The strange landscape of living and dying in the United States

By

The extraordinary pain of many people around you is unaddressed, and the scale of that unmet need would shock you if you saw it. Compartments of privacy separate you from the experience of your neighbors and even your own families. I understand that you have been unaware as well as hopeful that our medical system will either fix the problems or, at least, soothe the pain. It does neither consistently. The grappling of human beings to make sense out of the fact that they die has only been hiding in plain sight for a short time, and our society is awakening. That is both good news and a difficult truth.

Don was a “damn good” bookkeeper, he told me at our first palliative care visit in his home, and an amazing father according to his daughter. Don wished he hadn’t smoked the way he had, but 438,000 cigarettes later, he had widespread lung cancer. Taking a shot with palliative chemotherapy, neither of us had much confidence it would deliver value.

It’s a fair estimate that 107 billion people have been born in about 140,000 years of human history … the mothers and fathers of us all. Our modern medical system is less than 100 years old. Through technology and deepening understanding of our biology, lifespans are extended and the quality of life for most of us currently living is enhanced … for a while.

And yet, when we actually begin to complete our lives we do so without the simple things we need. For nearly all of human history, dying was no surprise as it occurred in close proximity to our living. In our modern system, we have hidden it away in hospitals, nursing homes and behind the closed doors of neighbors we don’t really know very well. The structures of coping were family and community, supported by the best efforts of those possessing certain skills directed at soothing the process without any illusions about changing the outcome. With such support, people died well, in peace, and with context. While our modern medical system brings enormous value to us while we navigate the beginning and the middle of our lives, it is an open secret that people have never suffered as badly as they do now as they complete their lives.

His weight continued to peel off, and even one cycle of chemotherapy was a “nightmare.” He accepted hospice without a lot of fanfare. With a long and short acting opiate, and a whiff of lorazepam at bedtime, his pain and breathlessness were well controlled despite increasing oxygen requirements. He got to work on “closing the books” and his daughter moved in.

A dynamic conversation about care for people with serious illness and those approaching death is exploding nearly everywhere in our society. From outside my field of palliative medicine, there is the work of Ellen Goodman and the Conversation Project, the intimate chronicles of Oliver Sacks last days in the New York Times, and the Institute of Medicine’s sentinel report on “Dying in America.” Atul Gawande with his bestseller, Being Mortal, offers his own awakening to the terrible truth of how our system of medicine fails to deliver the care needed and perpetuates the flimsy idea that we can fix anything.

From within the health care system, decades of effort from the likes of physician/author Ira Byock and trailblazing physician/ leader Diane Meier, as well as thousands of dedicated and inspired professionals, are bearing fruit to bring Palliative Care to central relevancy in discussions of health care delivery and reform. Baby Boomers like myself are being confronted with the truth of aging, the limits of technology, and the waste of a system that is doing exactly what it is designed to do. In his recent TED talk, BJ Miller put it simply, “Health care was designed with diseases at its center, not people. Which is to say that it is badly designed.”

As the weeks unfolded, Don’s world got smaller as he spent more time with the TV off instead of on. When I asked him about his process, he shrugged. He admitted that he was feeling physically better than he had now that the chemotherapy was cleared out, and that he was more relaxed with his daughter in the other room and hospice available anytime. “They are great, and a big relief.”

A millennial voice was also recently heard. That of Brittany Maynard, the 29-year-old Californian woman who relocated to Oregon to complete her life on her own terms with a legal and lethal prescription. In the last few weeks of her life, she pulled back the curtains and shared the experience of a modern death with a society that has had the habit of averting its gaze from such common experiences. With this act of empowerment and resolve, she has electrified the social discourse around self-determination and dignity, spurring California’s End of Life Option legislation. The bill was signed into law recently by a circumspect Governor Jerry Brown, and the landscape of self-determination was transformed.

His daughter thought he was too weak to make his way across the house to the cabinet where the medicines were kept. She had thought this thought because of hints and sideways remarks about “pointlessness.” Don would never be described as “patient,” she told me. In the dark and quiet of the night, he got up and did make what must have been an epic and lonely journey. He got all the pills, returned to his recliner, and removed his high flow oxygen before swallowing dozens of tablets. Alone.

For the last fifteen years, I have been a specialist in the field of palliative care and hospice. I have accompanied thousands of people and their families in the face of severe illness and a system of care that often fails to even avoid making their experience worse. I am a beginner. There have always been so many more people than there are teams of palliative care and hospice professionals to care for them, and this will be the case for decades. Even with the best palliative care and hospice support, we observe profound suffering, and we are often powerless to offer anything more than being there. That’s usually enough. But sometimes, it’s not even close.

As I move into a future where folks like Don and his daughter don’t have to be alone as they contemplate and choose their own path, my own sense of humility and respect for the people that seek my care continues to grow. When it comes right down to it, I trust people to know the path forward for themselves and I am honored that they allow me to accompany them.

This is a remarkable moment for our society for reasons far beyond any legislation. We are awakening to the truth of things. We are beginning to realize that the measure of us may have something to do with how we care for each other in our most difficult moments and how we address the deepest challenges faced by our society and our planet.

Perhaps, if we can begin to live life as if we won’t live forever, we can create a better world to live in and to die from.

Complete Article HERE!