The deathcare industry is changing, and with it are the ways we dispose of our bodies.

Situated just south of San Francisco, the small town of Colma, Calif., has become famous, or perhaps infamous, for its motto: “It’s Great to Be Alive in Colma.” Which is ironic, given that the town’s population of dead people far outnumbers its living residents by nearly 1,000 to one.

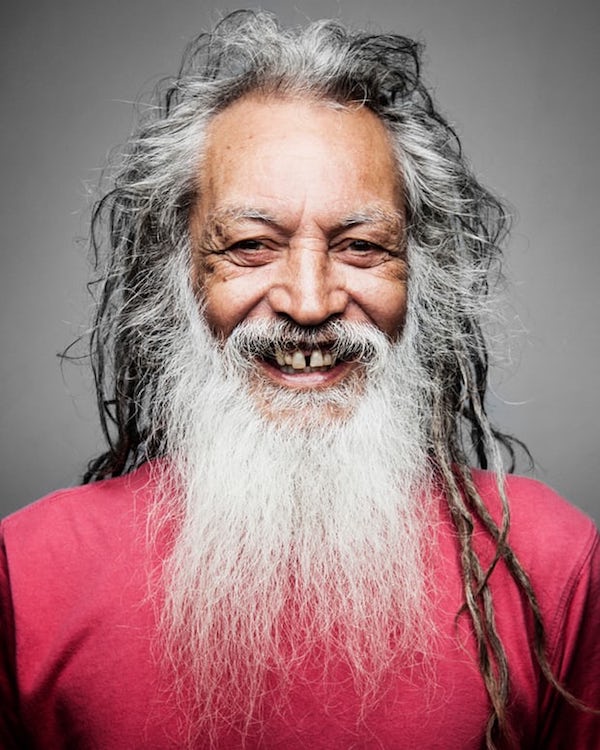

Among the living is Joe Stinson, 72, a funeral director and owner of Colma Cremation and Funeral Services. Over the course of his decades-long career caring for the dead, he’s seen a lot of changes the industry. The latest? A growing movement toward eco-friendly burials.

“Green burials are changing how we, as a society, look at burying our dead,” says Stinson, who believes that just as our own deaths are imminent, so too is the widespread adoption of environmentally friendly deathcare options.

In the past few years, a wave of eco-friendly startups have focused on how humans can continue to be good stewards of the earth even in our afterlife. At its core, a green, or natural, burial minimizes environmental impact by reducing carbon emissions and making sure no harmful substances leach into the ground. This can include biodegradable caskets, like those made from handwoven willow or seagrass, or simple cotton shrouds. And the use of the toxin formaldehyde to preserve a corpse is a definite no-no. After an unpreserved body is lowered into the ground, it eventually decomposes, mixing and nourishing the earth around it.

According to the Green Burial Council, which provides eco-certifications for burial practitioners and products, the number of GBC-approved providers in North America has grown from one in 2006 to more than 300 today. (To be sure, that number is certainly higher, as deathcare providers don’t have to be GBC-certified to offer green and eco-friendly options.)

The arguments for a more environmentally conscious burial are mounting, literally, as the concrete, steel and wood we bury along with our dead piles up. (According to one estimate, there’s 115 million tons of casket steel underground in North America, or enough to build almost all the high rises in Tokyo.) What’s more, the formaldehyde used in embalming is a known carcinogenic, putting funeral directors at a higher risk for cancer. Then there’s the pollutants — from embalming fluid to the toxic chemicals used in casket varnishes and sealants — that can seep into the groundwater. As for cremation, that takes an environmental toll too, as the burning of fossil fuels emits harmful carbon dioxide into the air.

“This, by no means, should be at the top of our environmental priority list, but it is something that can be easily dealt with,” says Phil Olson, assistant professor at Virginia Tech who specializes in death studies. “What we need to be worried about is the crap we put in the ground with the body. We need to talk about the environmental impact of forestry and all the energy it takes to manufacture the metals in coffins.”

Most green deathcare providers are hybrid operations, offering both conventional and natural burial options, but there are a few in the U.S. that specialize solely in green funerals and burials. One such operation is Fernwood Cemetery, located in Marin County, Calif., about an hour’s drive north of Stinson’s funeral home in Colma. On any given day at the bucolic cemetery, which sits above the rolling hills above Sausalito, you’ll find people walking their dogs, riding bikes or just lounging about. The only clue that it’s a burial ground is the occasional boulder engraved with someone’s name.

“We had some people coming through who were lost and asked what park we were in,” jokes Cindy Barath, the funeral director for Fernwood.

As for costs, well, that depends on where you live — or, rather, where you die.

Anyone in the cemetery business will say that death is like buying a house; it’s all about location. And in cities such as San Francisco, where there is more space devoted to housing and mixed-use buildings, creating an affordable option for a green burial is still a ways off. Fernwood, for example, charges between $10,000 to $15,000 for a full funeral, with a large chunk of that money going toward buying a plot of land. Compare that to the national average for a traditional funeral and burial, which is about $8,500.

Still, the costs for a green burial can be significantly less than a traditional internment, since you’re not paying for body preservation, an expensive casket made of steel or exotic wood, or a concrete grave vault. And some in the green-burial movement are working toward a model where a separate plot for each grave isn’t even necessary.

In Seattle, Recompose — formerly known as the Urban Death Project — is designing a three-story human-compost facility that turns dead bodies into reusable soil. The ambitious project, started in 2014, is still years from completion. If it succeeds, though, the company plans to replicate the model all over the world.

“Things in this industry happen slowly,” says Olson, referring to the snail’s pace of getting conventional cemeteries onboard with green burials.

In this regard, both Olson and Stinson point to cremation, which was introduced in the U.S. in the late 19th century. But it wasn’t until almost a hundred years later that cremations became more popular than burials.

Stinson, for one, is ready for the sea change he believes will eventually sweep the entire industry. Noticing the uptick in people requesting greener options, he’s begun offering more eco-friendly options, such as caskets made of seagrass and biodegradable urns.

For years, Stinson says, burials have always been fairly black and white: Either you’re cremated, or you’re put into the ground.

Looks like now we’re finally seeing shades of green.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!