By Tom Jokinen

In Winnipeg in a January blizzard, there are few places as toasty and sheltered as a crematorium. I know this because I worked in one. When the cremation chamber, or retort, is firing at 1,600 degrees Fahrenheit (900 Celsius), the work space is balmy, like a ski lodge. The noise of the powerful gas jets is buffered by the stone and steel of the machinery. When the gear is running, all you hear is a low, soothing rumble. It’s peaceful. I used to read Eudora Welty short stories while the body burned, stopping regularly to monitor temperatures and stoke the remains with an iron hook passed through a small, eye-level porthole in the oven door. The process is conducive to reflection.

Cremation seems clinical: fire, ashes. But in fact there is enormous spiritual heft behind it. We talk about the cleansing power of fire. As a funeral rite it goes back to the Bronze Age at least. “Fire,” writes the philosopher Gaston Bachelard, “magnifies human destiny, it links the small to the great, the hearth to the volcano.” Man “hears the call of the funeral pyre” not as destruction but as a road to renewal. This is overstating the case, as French philosophers do, but it still scans. Now try saying the same about a chemical process.

Last week, I read a story about a new process called alkaline hydrolysis. In a nutshell, it’s like cremation without the fire: The body is immersed in chemicals in a cylindrical device that looks (judging from the photo, as I’ve never seen one up close) like a large telescope with an Instant Pot lid. The chemicals break down the soft tissue, which is flushed away, leaving behind bones and any non-organic residue such as tooth fillings or artificial hips. The device is called a Resomator, a Doctor-Whovian commercial euphemism for what is basically a body-dissolving machine.

Industry licensing bodies such as the Bereavement Authority of Ontario are not sure what to make of alkaline hydrolysis. Is it safe to just flush the liquefied organic material into the city sewage system? Are there health risks? Is it dangerous or just very, very creepy? Is it any creepier than cremation – or burial for that matter? For now, though, its main selling point is that alkaline hydrolysis is considered greener, or less carbon-intensive, than other methods.

According to the Ecology Action Centre, the average cemetery buries 4,500 litres of formaldehyde, 97 tonnes of steel and 56,000 board feet of hardwood per acre. A single cremation, which intuitively (and emotionally) seems so clean and efficient, uses as much fossil-fuel energy as an 800-kilometre car trip. Sulphur dioxide and mercury are released into the atmosphere, up the flue. That warm feeling on a January day in Winnipeg comes at an ecological cost.

Meanwhile, hydrolysis uses one-eighth the energy spent in cremation. There is no embalming, no casket or container. Even with cremation, there is always a container of some kind, including, in my experience, very expensive hardwood caskets with brass trimmings. So alkaline hydrolysis is marketing itself thusly: your green alternative.

When you’re dead, there are few options for what happens next. I don’t mean spiritually – that’s between you and your God or His/Her metaphysical substitute. I mean with the body. We all leave a remainder. Some more than others. You can bury it, sink it in the sea, leave it in the trees or on hilltops to be devoured by carrion birds – known technically as excarnation, a natural process of removing the flesh before earth burial (in Tibetan and Comanche cultures, known as sky burial) – or most commonly you can burn it. In Canada, the cremation rate varies by region, but in 2018 more than 61 per cent of the dead in Ontario and Manitoba and more than 71 per cent in Quebec were cremated. The national cremation rate is expected to rise to 76.9 per cent by 2023, according to the Cremation Association of North America.

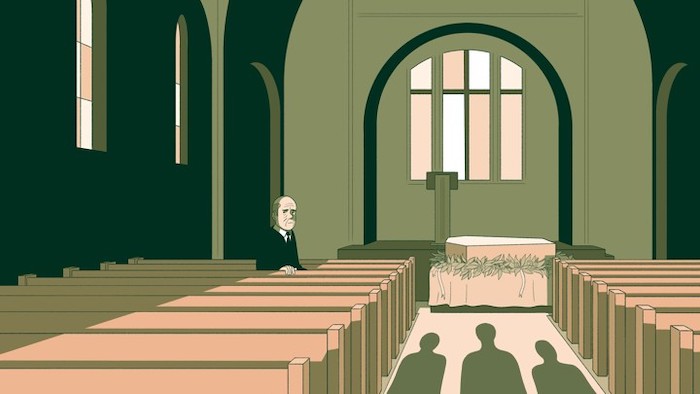

For the funeral industry, cremation has always been a shoe that pinches. It’s an industry based on the pricing of intangibles: the meaning of life and death, ritual, the concept of “closure.” It has been able to translate the emotional turbulence of death into product (caskets, vaults, embalming) and real estate (cemeteries), but over the past 50 years has watched as a cultural revolution changed everything. Religion loosened its hold, and fewer people felt bound by tradition. Cremation was cheaper. People moved around – for work, for relationships – and the idea of a permanent resting place lost its appeal. Postmodernism struck the funeral industry: Meaning and ritual came down to personal taste.

So the industry reinvented itself. Funerals became “celebrations of life,” and funeral directors became event planners like those who booked weddings (and the cost of weddings, they noticed, was skyrocketing). If cremation was on the rise, it could surely be monetized: urns shaped like golf bags, garden watering cans or basketballs, depending on the hobbies of the dead in question. Cemeteries focused on marketing columbaria, the small, above-ground vaults for urns.

I once met a cemetery salesman who assured me that scattering human remains was illegal (not true) and that he himself once stepped on a human bone on a beach in British Columbia (unlikely, as most crematoria process the remains to a fine, biologically inert powder). His sales pitch was simple: Only the industry knows how to handle what we all leave behind – the rest of us are not equipped. It’s a powerful message. As Jessica Mitford, author of The American Way of Death, found out, people will pay to avoid dealing with death and will subcontract what is basically an existential puzzle (what’s to become of me?) to a professional.

But it’s possible to be too clinical. We like at least a little meaning with our rituals, especially the death rituals. “Belief in a future state,” writes Bertram S. Puckle in Funeral Customs: Their Origin and Development, a 1926 text, “presupposed a material existence after death, with corresponding material necessities. Food must be provided, weapons and clothing, and a supply of charms with which to ward off evil influences.” And so even today people are buried with iPhones or cremated with a blanket from home. This is not superstition. It is about doing the right thing, even if the thing is a complete mystery. Alkaline hydrolysis is maybe too much like a chemistry experiment to bear much meaning.

And the industry continues to adapt and innovate. An Italian company used to market the Capsula Mundi, a starch-based, acorn-like pod that calls for no headstone as it, with the body, dissolves in time as compost and produces a tree. Demand, it turns out, was slim. Now the company offers an egg-like urn for cremated remains that does the same job for US$457 – tree not included. (But again, there’s the carbon footprint of the cremation itself.)

Straight-up green burial – in a shroud, with no embalming, in a legally designated forest (the law frowns on “freelance” burial) – is sparsely available. The industry has never embraced it.

Maybe it expects greater things from alkaline hydrolysis. After all, if meaning is and always will be knit deeply into our death rituals, it ticks the right boxes: In life, we rejected plastic straws and used twirly light bulbs. In death, we were thus safely melted. Carve it into your tombstone.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!