By Deb Gordon

If you think the cost of living in the United States healthcare system is high, wait till you see the cost of dying.

A new report details the direct financial impact of a loved one’s death, as well as the less tangible costs of loss.

The 2023 report on The Cost of Dying was released today from Empathy, a company that helps people manage the logistics and emotional burdens of death. The report includes results from a survey conducted with nearly 1,500 people who had lost an immediate family member in the prior five years.

Overall, the average direct costs related to the death of a loved one can reach $20,000. That’s before factoring lost income from taking time off or healthcare costs required to manage health and mental health symptoms.

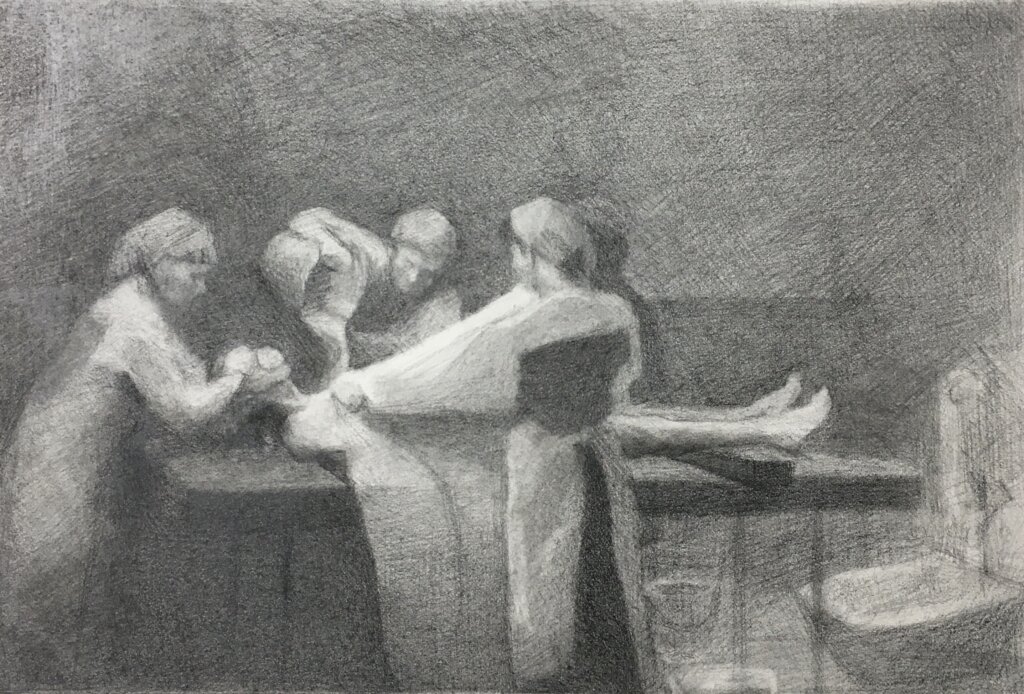

On average, survey respondents reported that they paid $3,584 to the funeral home (lower than the 2021 national median cost of $7,848 reported by the National Funeral Directors Association). Burial plots cost respondents an average of $1,841. Smaller expenses, such as catering, officiants, flowers, music, and invitations can add more than $1,700 combined, making the funeral the single biggest expense associated with a loved one’s death.

But the costs don’t end with the funeral. Survey respondents reported paying an average of $4,384 to deal with financial matters, such as hiring accountants and paying bills.

Respondents spent nearly $5,000 on legal matters, including lawyer fees and costs associated with selling off assets. Disposing of real estate can add another $4,000.

Many respondents reported using their own financial resources to pay death-related bills; 42% used their own credit cards or checking accounts and 36% used their savings. Just 14% were able to tap into funds specifically designed for these purposes, such as life insurance or last arrangements insurance.

Rinal Patel, founder of Pennsylvania-based Suburbrealtor, experienced firsthand the costs associated with the death of a loved one.

In February 2022, her 35-year old brother died of a heart attack while he was in Dubai for work. Patel spent more than $4,000 to fly his body back from Dubai and footed the entire bill for his funeral, about $10,000.

“He was my only brother, and I couldn’t let him be buried in a foreign country,” she said.

In addition to direct costs, Patel’s brother’s death also cost her income. As a business owner, Patel missed out on deals while she was away mourning her brother.

“His death cost me a lot financially, emotionally, and psychologically,” Patel said.

Lost work

Death-related costs hit at a time when many people can least afford them.

Nearly all (92%) employed respondents reported taking time off or adjusting their work commitments to manage the experience. For many workers, that costs them money indirectly.

Nearly one-quarter (23%) of respondents reported taking unpaid time off, while about half (51%) took paid time off. Women were more likely to take unpaid time off than men, and half as likely as men (9% vs. 19%) to report feeling satisfied with their employer’s bereavement leave policy.

Empathy’s report says that most U.S. companies offer one to five days of bereavement leave. But most people need more time than that to manage logistics of death, let alone to properly grief.

Jasmine Cobb, a licensed grief and trauma therapist from Texas, was lucky that she could use accrued paid time off when her mother died in 2020 from complications with metastatic breast cancer.

Though her employer at the time was supportive, Cobb noted the mismatch between most employer bereavement policies and employee needs.

“Generous bereavement is an oxymoron and is generally non-existent,” she said. “The most I’ve heard of companies extending is about two to three days max, which tends to be incongruent when experiencing a profound and significant loss.”

The health costs of death

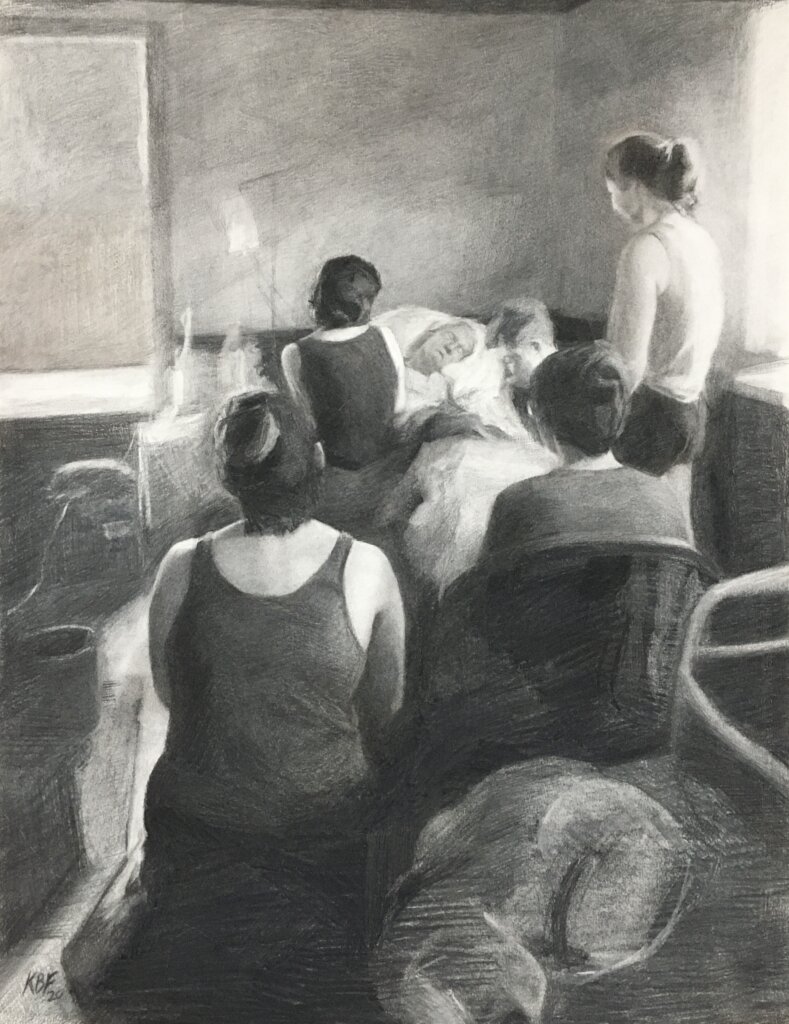

In addition to significant financial impact, 93% of survey respondents reported having experienced at least one health symptom as a consequence of their loss. A majority of respondents experienced at least two symptoms and 34% had four or more symptoms for more than a few months.

Persistent symptoms included anxiety, reported by nearly half (46%) of respondents. Other symptoms included disrupted sleep (38%), weight loss or gain (33%), irritability or anger (30%), and memory impairment (30%).

Women were more likely than men to experience symptoms for a year or longer. For example, 23% of women and just 12% of men reported experiencing anxiety for more than a year. Women were twice as likely as men to experience prolonged sleep disruptions (16% compared to 8%) and weight gain or loss (14% vs. 7%). One in ten (11%) women reported persistent panic attacks compared with 6% of men.

Tennessee-based Brittany Nicole Mendez, 27, a marketing officer at FloridaPanhandle.com, still experiences symptoms associated with loss, seven years after the death of her brother.

Mendez, then 20, was visiting her family in San Francisco for Christmas when she learned her 22-year old brother had been hit by a car while walking on a pedestrian crosswalk. He died the next day.

Though the direct financial burden fell to her parents, who started a GoFundMe to help with the unexpected funeral costs, Mendez didn’t get paid for the extra weeks she spent in California with her family.

The real cost to Mendez has come in the form of lasting mental health challenges.

“I never experienced true anxiety, panic attacks, or depression until after he passed away,” she said.

After her brother’s death, Mendez had difficulty eating and sleeping. She still suffers from extreme panic attacks caused by the fear that she or a loved one will lose their life unexpectedly.

Danielle Jones, 38, of Tampa, Florida, also experiences lingering health impacts of her mother’s death from heart failure in 2021. Jones’ mother died on her 57th birthday.

Jones paid for everything out of pocket, including travel and the process to clear out her mother’s house. She minimized expenses by replacing a funeral with visitation with specific friends and family. Her cousin, who worked for a funeral home, helped out by paying for her mother to be cremated.

But the nonmonetary costs have taken a toll on Jones.

“Her death rocked my world,” she said. “It was hard to go back to work. I cried between work calls.”

Jones started seeing a therapist, but the therapist was disorganized because she herself had just had a death in her own family.

“I quit seeing her,” Jones said. “I couldn’t handle the missed appointments.”

Jones said there were many nights when she could not sleep through the night. She said she only ate if someone reminded her to. Cooking, grocery shopping, and taking walks all reminded Jones of her mother. They would speak daily during these routine activities.

“I couldn’t walk int my kitchen because it made me think of her,” she said. “It was hard to get back to my life as I once knew it.”

Though Jones is a certified nutritionist and wellness strategist who writes about her experience with grief, she said she’s gained 20 pounds since her mother’s death. She blames the emotional stress of her grief.

It may be no wonder that the effects of death can last so long. The process of managing a death can take a lot longer than expected. Resolving all the financial matters associated with a loved one’s death took respondents about a year on average. They spent an average of 20 hours per week dealing with these issues. More than half (62%) said that these issues took longer to complete than they had expected.

Planning can offset the direct and indirect costs of death. Not only does it relieve financial burdens if some expenses have been prepaid, but people whose loved ones pre-planned their funerals reported missing less work and experiencing less anxiety, sleep disruption, and memory impairment. Pre-planning also reduced the likelihood that people would have trouble enjoying everyday activities after they lost their loved one.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!