In her new book, Hayley Campbell seeks to demystify death by sharing the perspectives of funeral home directors, gravediggers and others

What happens when people die is often glossed over. Yet as the adage goes, death is one of life’s few certainties.

Journalist Hayley Campbell in her new book, “All the Living and the Dead: From Embalmers to Executioners, an Exploration of the People Who Have Made Death Their Life’s Work,” sets out to demystify death by writing about “the naked, banal reality of this thing that will come to us all.”

It’s a subject for which Campbell, 36, has been preparing for most of her life. As a little girl, she recalls death being ever present — she drew dead bodies after seeing her comic book artist father’s graphic novel about Jack the Ripper in progress, questioned the version of death from her Catholic school education and saw her first body at 12, when her friend, Harriet, drowned while trying to rescue her dog. The London-based Campbell has since written regularly about death and related topics for Wired, BuzzFeed, Vice and other publications.

“On an existential level, we have to think about death; not only will we die, but everyone we know and love will die.”

In “All the Living and the Dead,” Campbell spends time with those whose professional lives revolve around death, including funeral directors, gravediggers and an executioner. Warning to anyone who’s squeamish: She provides vivid details of what it’s like to dress the dead, perform an autopsy and process bodies for use in medical education.

“On an existential level, we have to think about death; not only will we die but everyone we know and love will die,” Campbell told Next Avenue. “I can see why people would avoid that topic, but once you start talking about death with people for whom it’s their job, you can see how you can compartmentalize it.”

Here are some key takeways about death — and life — from Campbell and the book:

Death is Never Far Away, Whether We Acknowledge It or Not

As part of her research, Campbell went places where few civilians dare. “We don’t want to think about it, so it’s sort of a secret,” Campbell says of many death rituals. “I love seeing the stuff that as a general civilian person you can’t see. It can be behind doors you pass every day — on every high street, there is a funeral home — but you don’t realize something interesting is happening there every day.”

Even when we must go to a funeral home, whether to plan a service for a loved one or attend a memorial, the experience is usually a fleeting encounter. For those in the funeral industry, it’s their way of being.

“It was a huge privilege to talk to those people,” Campbell says. “The thing they kept telling me was they do this job every day. When families have to use them, the family will be hugely involved and their best friends for two weeks. After the funeral, they will disappear and go back to not thinking that embalmers exist. I wanted to get through the appreciation of the work that has to happen. The world would look completely different if we didn’t have people collecting the bodies.”

There’s a Difference Between Being Desensitized and Detached About Death

As we enter middle age, death becomes ever more prominent, as we face the loss of parents, siblings, close friends, a spouse or partner — and our own mortality. Yet few of us are prepared for major loss. But when death is your reality, you have to develop a way to compartmentalize.

“People think death workers must be desensitized, but there’s a difference between people being desensitized and detached in a way that’s helpful,” Campbell says. “They’re not not thinking about death — they have thought about it a lot and stepped back just enough to do their jobs. They have thought about it so much that they have made peace with it. But I don’t think we as a society have been able to deal with it. So when someone dies, we completely fall apart.”

A New Generation is Rethinking the Funeral Ritual

As a younger generation — including more women — enter the funeral industry, rituals and attitudes are changing. This might mean a more personalized funeral service, a natural burial without a body being embalmed or even loved ones participating in a traditional ritual like dressing the dead, as Campbell did as part of her research.

“The role of the funeral director has changed to more of a counselor role rather than someone who just organizes the hearse,” Campbell says. “I do think women are changing it. Female funeral directors are more into letting families do things the way they want. But if they want tradition, they will organize it with the horse and the cart. I think they are just more open — the thing that is common among all the women in the funeral industry is they want to give people a voice and not force a certain way of doing anything on anyone.”

“The role of the funeral director has changed to more of a counselor role rather than someone who just organizes the hearse.”

Details Matter When Handling the End of Someone’s Life

Whether it’s the funeral director who kept underwear and socks in different sizes because families often forgot to bring undergarments for their loved one and he couldn’t live with someone not being properly dressed in their casket — or a gravedigger who provided a certain type of soil for the minster to throw on a coffin that would land more softly, those dealing with death regularly understand the difference the smallest details can make.

“They all had a sense of compassion and a sense of empathy,” Campbell says. “They all were doing little things in their job that no one would notice but they felt was the right thing to do. It may seem like something small, but when you think about grieving people and how they are so sensitive to everything, they are massive.”

Death Has a Way of Grounding You

Having written about death for most of her career, Campbell is not someone who’s faint of heart. But having immersed herself in death for three years to write the book, she came away with a new appreciation for life.

“It’s not like my eyes have been opened to things that I didn’t know about but the details have been filled in,” Campbell says. “I’ve seen dead babies and old, old dead people. I’m far more conscious of the old cliché that life is short. That is true, but you have no idea how much time you’re going to get. I think I’m more conscious of time.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Health Proxy

— Giving Voice to Those Unable to Speak

Choosing a healthcare proxy could be one of your most important decisions. As your medical decision-maker, they’ll be your voice if you become too sick or injured to speak for yourself. They tell the doctor whether to continue lifesaving treatment or whether to stop treatment. They know which family members you want visiting you and which you don’t. They know what you want because they’re someone you trust.

- A health proxy holds the power of attorney to make health care decisions for you when you can’t because of illness or injury.

- Choosing a health proxy is part of end-of-life paperwork called your advance directive.

- The paperwork is simple but choosing the right person can be tricky.

- You’ll want to pick someone you trust who’s up to the task.

- People who complete health proxy and living will paperwork are three times more likely to have their end-of-life wishes followed.

- Learn how to choose a proxy, discuss it with them, and make it legal.

Surprisingly, however, the best proxy may not be your partner or your adult child. Choosing the right person can be more complicated.

A health proxy is your voice

If you’re whisked to the hospital after a car accident, unconscious and traumatically injured, who will speak for you if you can’t talk? A health proxy is your health care agent who voices the type of medical treatment you want if you’re incapacitated, the legal term for being unable to manage your affairs because of sickness or injury.

Another name for a health proxy is a surrogate decision-maker. Your proxy has the power of attorney to make health care decisions for you. Those decisions may affect the hospital bill, but a health proxy can only make medical decisions, not financial ones.

How does it work?

Choosing a health proxy is part of an advanced care planning process. Advance directives are the legal advance care documents describing your wishes for end-of-life care. Part of the purpose of the paperwork is to name a health proxy.

Choosing one is a simple process but can be emotionally trying:

- Choose someone you trust to make such decisions for you.

- Talk with them about the role and your end-of-life wishes.

- Sign the official paperwork together.

- Give your medical team and loved ones a copy of the document.

How to pick the right person

Rules can vary between states, but generally, your proxy must be over 18, can’t be a part of your current medical team, and shouldn’t be someone who will receive an inheritance or other benefits after you die.

Otherwise, you can pick nearly anyone to be your health decision-maker. Your proxy can be a family member, a partner, a friend, a spiritual leader, a neighbor, a coworker…you get the idea. They don’t have to live close to you, but that can be helpful for some people.

First, think about the people you trust and those who know you best. Second, consider whether they’re up to the task.

Surprising to some, a partner, adult child, or parent may not be the best proxy for you. The task is too painful or daunting for some loved ones.

Your decision-maker will have to make tough decisions in the heat of a traumatic moment involving paramedics or hospital staff. They’ll have access to your medical records and will be the communicator between your doctor and loved ones. Deciphering medical language and asking questions requires someone bold to advocate for you. Who do you want to decide “when to pull the plug?”

It’s also wise to pick a second proxy in case your primary health agent is unavailable.

If you can’t think of the right person right away, you must complete the second part of your advance directives – your living will – and talk with your doctor. This document outlines what kind of medical care you want in certain circumstances that bring you near death. It’s different from the more common will that directs financial and asset decisions after you die.

If you don’t have a personal advocate, the living will champions your wishes.

If you have no one you trust and no close relative, a court may appoint a surrogate decision-maker for you.

With this powerful living will in hand, you are three times more likely to have your wishes followed, says emergency doctor Elizabeth Clayborne in her moving TEDx video.

Isn’t my spouse automatically my proxy?

In most states, yes, including domestic partners. If you don’t have a partner, most states will default to your next closest relative, adult children first and parents second.

Even if you are married or close to your children or parents, are they the best decision-maker for you? The decisions can be too heavy for some people to bear. Instead of choosing a close loved one as your healthy proxy, you could require the proxy to consult with that loved one before making a decision.

How to talk with your proxy

Talking with your medical decision-maker empowers them to make the best decisions for you.

First, discuss the role. Be sure they understand what it means to be your proxy. Allow them to say no if they need to. Take time to answer their questions.

If they agree, start talking about the details like:

- Your medical history

- Medications

- Allergies

- Medical treatments you don’t want

- Life-saving treatments you want and when

- The life-saving treatment you don’t want and when

- Where do you want to die

- Who do you want to visit you

- Who you don’t want to visit you

- Who you do and don’t want to be updated about your medical situation

- Spiritual or religious wishes

Write down as many of these details as you can for your decision-maker. A living will is the best way to document your wishes. It could be helpful to give your proxy The Conversation Project’s booklet about how to be a health proxy.

Make it legal and spread the word

You don’t need a lawyer to complete health proxy documents. Most states do require two witnesses to watch you sign the form. They may also require a notary to notarize the signed form. Each state has different advance directive forms. You can find the right form on trustworthy sites for free.

Once the form is complete, give copies to your health proxy, your loved ones, and your doctors.

Don’t lock the form away in your safe or safety deposit box. Be sure it’s easy to find for anyone in your home.

You’ll want to give copies to loved ones who are not your health proxy, too, so they clearly understand the plan. As for those you don’t want to be involved in your care, tell them, too. They need to know who will be speaking for you.

These can be taxing discussions. Be sure to talk to a counselor, a friend, or a spiritual advisor if needed.

Your health proxy isn’t set in stone.

You can change your healthy proxy at any time. You can also update your living will at any time. Keep the thinking and talking going and update your documents and your health proxy accordingly. Big life changes like having a child, getting married, or facing a serious diagnosis can all affect your end-of-life choices.

Now that you know what a health proxy is and are thinking about your-end-of life wishes, why not take the final steps and complete the paperwork? Just be sure to finish. Don’t let the power of medical decisions slip out of your hands.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Dia de los Muertos (Day Of The Dead) 2022

More than 500 years ago, when the Spanish Conquistadors landed in what is now Mexico, they encountered natives practicing a ritual that seemed to mock death.

It was a ritual the indigenous people had been practicing at least 3,000 years. A ritual the Spaniards would try unsuccessfully to eradicate.

A ritual known today as Dia de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead.

The ritual is celebrated in Mexico and certain parts of the United States. Although the ritual has since been merged with Catholic theology, it still maintains the basic principles of the Aztec ritual, such as the use of skulls.

Today, people don wooden skull masks called calacas and dance in honor of their deceased relatives. The wooden skulls are also placed on altars that are dedicated to the dead. Sugar skulls, made with the names of the dead person on the forehead, are eaten by a relative or friend, according to Mary J. Adrade, who has written three books on the ritual.

The Aztecs and other Meso-American civilizations kept skulls as trophies and displayed them during the ritual. The skulls were used to symbolize death and rebirth.

The skulls were used to honor the dead, whom the Aztecs and other Meso-American civilizations believed came back to visit during the monthlong ritual.

Unlike the Spaniards, who viewed death as the end of life, the natives viewed it as the continuation of life. Instead of fearing death, they embraced it. To them, life was a dream and only in death did they become truly awake.

“The pre-Hispanic people honored duality as being dynamic,” said Christina Gonzalez, senior lecturer on Hispanic issues at Arizona State University. “They didn’t separate death from pain, wealth from poverty like they did in Western cultures.”

However, the Spaniards considered the ritual to be sacrilegious. They perceived the indigenous people to be barbaric and pagan.

In their attempts to convert them to Catholicism, the Spaniards tried to kill the ritual.

But like the old Aztec spirits, the ritual refused to die.

To make the ritual more Christian, the Spaniards moved it so it coincided with All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day (Nov. 1 and 2), which is when it is celebrated today.

Previously it fell on the ninth month of the Aztec Solar Calendar, approximately the beginning of August, and was celebrated for the entire month. Festivities were presided over by the goddess Mictecacihuatl. The goddess, known as “Lady of the Dead,” was believed to have died at birth, Andrade said.

Today, Day of the Dead is celebrated in Mexico and in certain parts of the United States and Central America.

“It’s celebrated different depending on where you go,” Gonzalez said.

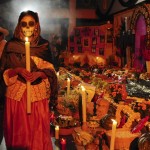

In rural Mexico, people visit the cemetery where their loved ones are buried. They decorate gravesites with marigold flowers and candles. They bring toys for dead children and bottles of tequila to adults. They sit on picnic blankets next to gravesites and eat the favorite food of their loved ones.

In Guadalupe, the ritual is celebrated much like it is in rural Mexico.

“Here the people spend the day in the cemetery,” said Esther Cota, the parish secretary at the Our Lady of Guadalupe Church. “The graves are decorated real pretty by the people.”

For more information visit HERE!

Celebrating the Day of the Dead with my students helped me overcome my fear of death

- My Spanish classroom is covered in flowers and glitter as we prepare to celebrate the dead.

- While death is often a taboo topic in the US, in Mexico the dead are widely celebrated.

- Celebrating the Day of the Dead, or Día de los Muertos, has taught me not to fear my own death.

The third time I wound up in the emergency room struggling to breathe, I started to consider my mortality.

When I was a child, asthma landed me in an oxygen tent for a week. As an adult, when even my rescue inhaler and nebulizers couldn’t help my lungs, I unconsciously started writing my own obituary.

I tried not to think about death. But it always lingered, in a spooky, dark corner of my mind.

Americans largely don’t talk about death, as if mentioning it would summon the Grim Reaper. In a survey conducted in April by Chapman University, 29% of respondents indicated they were afraid or very afraid of dying. A 2013 article in Psychology Today described death as the US’s “leading source of uneasiness, discomfort, and apprehension.”

My Spanish class showed me how to celebrate

There’s no better time of year to witness our culture’s fear of death than during Halloween, when we adorn our yards with skeletons, mummies, and zombies.

In my Spanish classroom, however, we observe differently.

This time of year, my classroom floor is covered in glitter and brightly colored feathers. My students are putting the finishing touches on their sugar skulls for Día de Muertos, which falls on November 1 and 2. In Mexico and around the world, people remember loved ones who have passed on with altars, marigolds, photos, offerings, and celebrations.

As a Spanish teacher, I started introducing my students to Day of the Dead about five years ago. We learn about how the Day of the Dead is celebrated in Mexico and make skeleton puppets, sugar skulls, or altars. I ask my students to think of a loved one who has died and draw an altar for them. We sit in a circle and talk about which artifacts we would place on an altar to conjure our loved ones for a night of fiesta.

Mexican tradition holds that the dead would be offended by grieving and sadness so the festivities should be joyful and full of laughter.

The Mexican poet Octavio Paz once said: “To the people of New York, London, and Paris, ‘death’ is a word that is never pronounced because it burns the lips. The Mexican, however, frequents it, jokes about it, caresses it, sleeps with it, and celebrates it. It is one of his favorite toys and most steadfast love.”

COVID-19 made me reconsider things

Then COVID-19 came. Knowing that a respiratory disease could put me at greater risk of illness or even death, I considered the possibility that I could die tomorrow.

Death no longer felt like a spooky shadow that needed to be avoided. It had always been there, always would be. But that shadow was now adorned with flowers and color and photos of loved ones.

Psychologists talk about naming, confronting, and reframing our fears to help us overcome phobias. By allowing the brain to get used to a feared object or situation, we can adjust how we respond.

Carlos Olmedo, the director of the Dolores Olmedo Museum, explains it this way: “For Mexicans, death was part of life. For us, it was like going from day to night so we didn’t feel something we were losing; it was just a step more.”

Celebrating Día de los Muertos with my students and children has helped me reframe how I view death and dying. It no longer feels like something separate from life but as something that’s connected, just as the day and night are connected — no longer a loss, but another step.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Death is a part of life that kids need to understand, no matter how hard it is

Why is it taboo to talk about dying? And how can we talk to our kids about it?

by Amy Bell

Death is a fact of life. But it’s one that many people would love to avoid talking about at all costs.

Maybe it’s superstition: somehow, if we don’t speak of it, it won’t affect us. But death is inescapable.

So how do we prepare our kids to confront loss?

‘We are a death-denying society’

Christa Ovenell is working hard to change the dialogue and attitudes around death.

She’s an end-of-life educator and created the Vancouver-based organization Death’s Apprentice as a way to help people and families openly prepare for death and accept it as a natural progression of life. But it’s a hard switch to flip in a society that holds youth and vitality in such high regard.

“Think about, for example, in Mexico, where we would have a weeklong celebration for the Day of the Dead, that we would actually go and make our dead a part of our life,” says Ovenell.

“We don’t do that here. Because we are a death-denying society. And that’s what makes it so hard.”

Use straightforward language

The death of a loved one can be incredibly difficult, but for kids it can be especially confusing.

You could throw on an endless loop of Disney movies where someone’s mother always seems to be dying, or you could simply talk about death — and how it’s a completely natural part of life — before big emotions become attached to it.

Ovenell wants death to be normalized and openly discussed from an early age, just as we’ve become more open to talking about sexual health and addiction, for example.

A good start is using straightforward language, “the way we do in other tough or difficult conversations,” she says.

“Real words like, ‘someone died,’ or, ‘the cat died.’ Just normalizing it, making it just part of what kids hear, instead of funny things like, ‘Grandpa is resting,’ or, ‘so-and-so has passed.'”

Openness toward death needs to extend to all ways in which life can end. There are no “good” or “noble” ways people die. Whether from suicide or an overdose, everyone’s life has meaning and should be mourned when it ends.

Memories last

Once someone a child knows dies, it can be difficult for a parent to help them process their feelings while grieving themselves. Grief is not a linear process and it raises many emotions.

Local mom Megan Cindric says the recent and sudden loss of her father has deeply affected her and her twin daughters, Fiona and Lily. Cindric wants to make sure her daughters know however they choose to remember their grandfather is valid, and that she’s just as affected by the loss.

“I am still sad every single day, and so I think it’s completely normal that Fiona is sad every day,” says Cindric.

“When she does get sad I tell her that I understand because I’m sad every day, too. And this is very normal because we loved Grandpa and we still love Grandpa.”

Cindric found both her girls understood their grandfather’s passing once she explained that he was more than just his body, and that would never change.

“I told them … when his body just couldn’t live any more, I could tell that he was different. I could tell that all of the things that made him Grandpa — his energy and his love and his spirit — I could tell that it was gone.

“I could tell that his body had stopped but all of his ‘Grandpa-ness’ had gone somewhere else,” she says.

Religion can bring many people comfort when it comes to confronting the afterlife, but some find solace elsewhere.

Cindric says she was recently in the garden her father had lovingly tended for years when a little green frog came and sat on the colander she was holding. When she told her girls about it, Cindric says they all agreed on one thing: “Fiona said, ‘I think that was Grandpa,’ and I said, ‘I kind of thought it was him, too.'”

There are two things in life we all experience without fail: being born and dying. While one event is celebrated, the other we spend our lives trying to outrun.

But like many topics that have made us uncomfortable in the past, if we push through that discomfort and openly discuss them with our kids, we take their fearful power away.

No matter who we’ve lost, their lives have affected us for the better — and death can’t ever lessen that.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The 5 Best Self-Help Books To Read During The Grieving Process

By Brie Schmidt

Grieving the loss of a loved one tops the list of the most stressful life events, according to Verywell Mind. Grief can feel like sadness, anger, confusion, shock, guilt, and emptiness — or even multiple emotions, all experienced at once. And though time may not completely heal all wounds related to loss, grief can be processed and managed over time with the help of therapy, a trusted support network, and gentle self-care days.

Another source of comfort can be found in self-help books about loss. Bereavement resource website Grief and Sympathy explains that reading books about grief and death can expose us to stories of other people’s losses, helping us to feel less alone. Additionally, some books are written by mental health experts who offer research-backed advice and useful coping strategies.

If you’ve recently experienced the death of a loved one, turn to these five self-help books to help walk you through the grieving process.

How To Go On Living When Someone You Love Dies

Therese A. Rando, a clinical psychologist who specializes in trauma and grief, wrote “How to Go on Living When Someone You Love Dies” in 1991, and the book has remained a go-to for those in mourning ever since. “How to Go on Living When Someone You Love Dies” acts as a comprehensive guide to grief, offering both emotional and practical guidance, from how to cope with loss during the holidays to how to plan a funeral.

This book is an all-in-one starter if you’re unsure how to pick up the pieces following death. And in the months and years following, too, its gentle advice continues to prove useful on those days when grief reappears.

It’s Ok That You’re Not Ok

“It’s OK That You’re Not OK” may be just as helpful for the bereaved as it is for their friends and loved ones who aren’t sure how to respond. The book, written by Megan Devine after she tragically lost her partner (per The New York Times), treats grief as a natural response to death, not as a feeling to be minimized.

“It’s OK That You’re Not OK” offers essays, practical life advice, and research to normalize every step of the grieving process. For those looking to make space for their feelings, in a society where those feelings aren’t always understood, this book is indispensable.

The Other Side of Sadness

If you want a scientific understanding of the grieving process, look to “the most renowned grief researcher in the United States,” according to The Atlantic, George Bonanno. His book, “The Other Side of Sadness,” offers digestible research along with the story of Bonanno’s own loss of his father, to help make sense of grief’s complex emotions.

“The Other Side of Sadness” offers a much-needed reminder that there’s not one “right” way to experience loss. In particular, this book is ideal for those who grieve quietly or with a sense of relief or happiness, emotions that aren’t often discussed in grief self-help books.

Goodbye, Friend: Healing Wisdom for Anyone Who Has Ever Lost a Pet

The loss of a pet can be just as devastating as the loss of a human family member. Yet the grief that can follow the loss of a furry friend isn’t often discussed or validated in society, and many loved ones may not know what to say when someone’s pet dies. The bond shared with a pet is a special one and can require a different approach than the stories and research often shared in self-help books on grief.

That’s where “Goodbye, Friend” comes in. The book, written by Gary Kowalski, honors the connection humans share with their animal friends with chapters on processing death, talking to children about pet loss, and giving pets a loving goodbye.

Bearing the Unbearable: Love, Loss, and the Heartbreaking Path of Grief

“Bearing the Unbearable” understands that grief can be an all-encompassing experience, one where you may not feel ready or able to sit down and focus on long book chapters. That might be why this book contains short, easy-to-read sections, making it an approachable companion during life’s hardest times.

Author Joanne Cacciatore is an expert in grief, having counseled people experiencing traumatic loss, as well as navigating the loss of her daughter and other beloved family members. “Bearing the Unbearable” puts the grieving process into relatable words through personal accounts that are just as tear-jerking as they are comforting.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

It’s time we talk honestly about grief in the workplace

— As we continue re-writing the rules of work, it’s time to address one of the biggest taboos in life and work: death.

By Lars Schmidt

I’ve been living with grief most of my life.

I lost my mother to a long battle with multiple sclerosis in my early 20s. I lost my father to cancer in my early 30s. I lost my brother, the last remaining member of my immediate family, to addiction in my late 30s.

My experience isn’t unique. We’ve all lost loved ones. We all carry the scars of grief, heartbreak, and loss. And yet, despite the fact that death is a part of life, we rarely discuss it candidly. That lack of openness creates a stigma that isolates those grieving in their greatest time of need.

This is especially true when it comes to work—a place where we spend so much of our lives. In these settings, we’re expected to compartmentalize our feelings and carry on.

As more companies embrace mental health as a fourth pillar of employee benefits, it’s time they factor in grief in all its forms into their programs. Grief-specific training for managers. Rethinking bereavement policies. Support systems for employees. Flexible leave programs beyond the traditional bereavement period. Normalizing (and even encouraging) conversations on grief at work.

Death, loss, and grief are universal conditions. While our journeys through grief are individual, the experience is collective. It’s time we recognize that reality and bring more empathy to how we support grieving employees.

Carrying the Weight of the World

Despite the fact that many workplaces maintain an outdated perspective toward grieving, the pandemic has brought death and suffering to the forefront of our consciousness. According to the World Health Organization, we’ve lost 6.54 million lives to COVID-19 over the past two-plus years, including over one million lives lost in the United States alone, making COVID the third-leading cause of death in 2021, according to the CDC.

COVID grief is not limited to death. Research from the Brookings Institute shows Long COVID may be keeping four million people out of work in the United States alone. The loss of lifestyle and agency creates its own type of grief and mental health struggles—a risk that may be exacerbated in cases where psychological stress existed before infection, according to researchers at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The pandemic–fueled increase in mental health struggles is a global phenomenon. Earlier this year, the WHO cited a 25% increase in anxiety and depression worldwide. “The information we have now about the impact of COVID-19 on the world’s mental health is just the tip of the iceberg,” said Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General in a scientific brief published earlier this year. “This is a wake-up call to all countries to pay more attention to mental health and do a better job of supporting their populations’ mental health.”

The stress and burdens society carries show up in life, including work. It’s time employers rethink how they meet this moment.

It’s easy to get lost in the numbers above as just data, but we can’t forget what they represent. Mothers. Fathers. Neighbors. Colleagues. Mentors. Friends.

The human toll of the pandemic and the mental health struggles that have been building over the past several years will continue to have a profound impact on our society and our workplaces for years to come. The time for companies to adapt to this reality is now.

The Toll of Unresolved Grief

The journey through grief is nonlinear. For some, grief is an acute pain followed by a full recovery. For others, grief is an endless sea with waves that ebb and flow for eternity.

Living with grief in the latter scenario can create a range of mental health challenges, as McKinsey explored in their study, “The hidden perils of unresolved grief.”

The study found that unresolved grief costs companies billions of dollars annually in lost productivity and performance. It found that unresolved grief is a pervasive, overlooked leadership derailer that affects perhaps one-third of senior executives at one time or another.

Living with grief means you often don’t have control over when these emotions manifest. The mental health struggles of navigating this pain are very real. Grief triggers can be known: birthdays, anniversaries, songs. They can also come from seemingly nowhere and send you down a spiral of emotions.

I vividly remember a work offsite at a former employer where we were asked by a facilitator to point to where we were from on a map. It was two years after I lost my father and I was still processing that pain.

When it was my turn to point, I couldn’t. The seemingly benign exercise of pointing to your hometown on a map made me think of what I no longer had there: the deep voice and warm embrace of my father that was gone forever. I broke down in front of my entire team, and had to step away from the exercise.

Living (and Working) With Grief

Grief and recovering are personal, individual journeys, yet most employers view them as one-size-fits-all. Bereavement plans are typically three to seven days in the United States. Rigid applications of the guidelines are not nearly enough to account for the post-grief emotional haze that can last weeks or more.

Kyle Cupp, manager of content services strategy at Mineral, tragically lost his son Jonathan and shared his experience in a USA Today piece. “To my colleagues, I probably appear to be holding up reasonably well,” he wrote. “I’m able at times to smile, laugh, and joke. That isn’t to say my grief isn’t evident to the members of my team, however blurred it may be over the computer screen. … You can’t keep grief out of the workplace. It will be shared. The alternative is to make a place for it.”

When you make place for grief in the workplace, you give grieving employees space to deal with their emotions as they come. You remove the need for a forced-compartmentalization veneer of normalcy and allow employees to navigate their grief at their own pace. Employers who recognize that the grieving process comes in waves and make that support clear to employees (and their managers) will benefit long-term from the empathy and care they show grieving employees.

Lisa Lee lost her father in 2019. She shared her experience processing her grief in a Medium story, Grief and Work. In it, she shares how being able to speak openly about her father provided comfort in the days and weeks after his death.

“Coming back to work, I noticed that talking to and being around colleagues who have met Mr. Lee or are at least familiar with my family made me feel less lonely. I’m sure it’s because their simple presence in my life confirmed that he was real—it was a temporary med to the shock of having him there one day and not the next. I knew that as hard as it would be to talk about him, ‘giving in’ to my thoughts by addressing them in a managed way actually helped me to get through each day.”

How can employees meet this moment and adjust their approaches toward grief?

New platforms like Betterleave are being created as a workplace benefit to help employees navigate everything that comes from bereavement to estate planning. These resources are helpful support for grievers, but we need to go broader and deeper to create a workplace that can help the healing process.

That includes grief counseling that extends beyond the grievers, more support for managers helping their employees as they navigate loss, and normalizing these conversations from the top on down.

Death, grief, and loss are universal. The taboo-driven isolation that accompanies our inability to discuss it doesn’t have to be.

If you’re experiencing grief, I know how isolating it can feel. Please know you’re not alone.

I recently covered the topic of living with grief in my podcast. The post below includes a range of resources, books, podcasts, and stories to support those of you grappling with grief. You can find it here.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!