Do we ‘do’ death best?

Collection features 75 perspectives on death in Ireland and whets appetite for further study

By Bridget English

[T]he Irish wake is nearly as celebrated and stereotypical an Irish export as Guinness, leprechauns or shamrock. Its reputation as a raucous, drunken party that celebrates the life of the deceased is now regarded internationally as a desirable way to mark the end of one’s life, even for those who claim little or no Irish heritage.

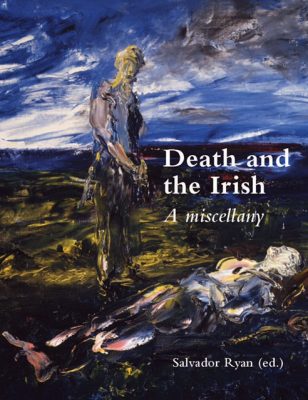

It is conceivable, then, given the famous link between Ireland and death, that the Irish “do death well”. Where does this association come from? Do the Irish really “do” death better than anyone else? These are some of the questions behind a new collection of essays, Death and the Irish: A miscellany, edited by Salvador Ryan, a professor of ecclesiastical history at St Patrick’s College Maynooth.

The collection is part of a recent surge of academic interest in death and dying, as is evidenced by the publication of edited collections such as Grave Matters, Death and Dying in Dublin, 1500 to the Present (2016), edited by Lisa Marie Griffith and Ciarán Wallace, and Death and Dying in Ireland, Britain and Europe: Historical Perspectives (2013), edited by James Kelly and Mary Ann Lyons, both of which explore these themes from a historical perspective.

>Subtitled “a miscellany”, Death and the Irish is different from these publications because it features a medley of 75 perspectives on death and the Irish from historians, hospice workers, geographers, sociologists, anthropologists, theologians, priests, librarians, musicologists, and funeral directors, to name a few. It also covers a vast time span, taking readers from the fifth century to the present day.

Entertainment

The brevity of the essays (around three to four pages, including footnotes) and their pithiness, though a departure from the extended discussions commonly found in academic anthologies, is true to the form of the miscellany, which was originally intended for the entertainment of contemporary audiences.

Death and the Irish will interest readers looking for interesting tidbits of information on death and provides ample fuel for those searching for inspiration for further research.

Some tantalising morsels from the miscellany include: the tale of a young woman buried with her horse sometime between 381 and 536 AD; the variety of terms for death in the Irish language; social media’s role in keeping memories of the dead alive; an analysis of Stuart-era funerary monuments and what they reveal about women’s role in society; the 18th-century Dublin practice of laying executed corpses at the prosecutor’s door; a quirky account of the discovery of James McNally’s death by elephant in Glasnevin cemetery’s burial registers; and the story of a young cabin boy’s death by cannibalism.

Given the number of entries included in the volume, it is not possible to provide a detailed account of each, but a few entries are worth mentioning. Clodagh Tait’s Graveyard folklore and Jenny Butler’s The ritual and social use of tobacco in the context of the wake are particularly thought-provoking accounts of folk practices and the material cultures surrounding death. Tait’s gruesome description of the pieces of human remains that were collected for charms and the dead man’s hand that “could be used to make churning butter less onerous” provides readers with images that they are unlikely to soon forget.

One downside of Death and the Irish is that the experience of reading such short essays can be frustrating for anyone (particularly students) coming to the collection looking for an extended discussion of death practices in a particular era. Organising the entries by time period or by theme (burial, folklore, historical figures or events, etc) might make for more streamlined reading, but to do so would also destroy one of the collection’s main strengths, which is to bring disparate approaches together, taking interdisciplinarity to an extreme, provoking new ideas through a multilayered view of death in Ireland.

Under-represented

Despite the inclusiveness of Ryan’s miscellany, certain disciplines, such as history and theology, seem to dominate, while others are absent or under-represented. Philosophers have certainly shaped the ways that modern secular society conceives of death, yet there are no entries on the relationship between Ireland and philosophy.

Irish film, literature and drama feature some of the most insightful and humorous portrayals of death and dying in western culture, yet there are only three entries on literature, and these are limited to poetry (Irish language poetry, bardic poetry and 18th-century elegies).

These are minor criticisms and on the whole, Death and the Irish: A miscellany is commendable for its inclusion of marginalised groups such as Travellers, and for the links made between Irish practices and Jewish and Muslim beliefs. The Irish may not necessarily “do” death better than anyone else, but as this volume makes clear, the history and rituals surrounding death offer a rich and complex area of study, one that has much to tell us about Irish attitudes towards mortality and treatment of the dead.

Complete Article HERE!