— Reframing life in terms of death reveals some of the biggest philosophical problems with how we think about living systems.

By Adam Frank

Definitions of life are notoriously hard to pin down. Is a fire alive? It has a kind of metabolism, and in a sense it reproduces by spreading. Is a crystal alive? It certainly grows. What about a virus, which can reproduce and mutate, but only if it can find a living cell to use as a host?

Scientific definitions of life tend to focus on things like reproduction, metabolism, heredity, and evolution. But there is another, more basic property of life that has profound consequences for its study, and which I want to explore today: the capacity to die. While this may seem obvious, reframing life in terms of death reveals some of the biggest philosophical and scientific problems with the way we think about living systems.

You are more than your DNA

Focusing on the biomolecular mechanisms of life has yielded remarkable insights into what happens inside cells. However, this emphasis over the last 70 years on molecules such as deoxyribonucleic acid has produced a kind of myopia that can lead researchers to blind themselves to a critical insight. Life is not just molecules. It cannot be reduced to the interactions of a set of molecular actors. Instead, life is really about organization. This is why, alongside the emphasis on biochemistry, there has always been a focus on life as an organism. An organism is a whole that is also wholly invested in its interactions with the environment. Biomolecules would never take on the activities they play in the cell were it not for the higher levels of organization the cell makes possible.

And this is where death comes in.

Biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela developed the concept of autopoiesis in the 1970s and 1980s to describe the essential character of life as an organism. Autopoiesis means “self-producing.” The term, which Maturana and Varela coined, refers to a kind of strange loop that occurs in living systems whereby the processes and products needed for an organism to survive must be created by the processes and products needed for the organism to survive. The classic example is the cell membrane, whose presence is required to create the very compounds that maintain it.

Over the next year I will be writing more about autopoiesis, as it forms part of a new research program on life and information funded by the Templeton Institute. The key point for today is to understand that one thing Maturana and Varela wanted to focus on with autopoiesis was its intrinsic capacity to end. To be an autopoietic system is to constantly face death.

To be alive is always to live in a “precarious condition,” as Varela called it. You, me, a butterfly, a single-celled organism — all life must constantly be at work to produce and maintain itself. Life can never take a rest from the internal activities it must carry out to do that. And this self-production and self-maintenance must work on a remarkable array of scales. At the molecular level, the ribosomes that drive life’s nano-machinery must never halt. At the cellular level, the membrane can never stop its work of monitoring and adjusting the flux of compounds into the cell. At the system level in more complex life, the various components of a plant or animal must always be synchronized and synchronizing.

Or else, what?

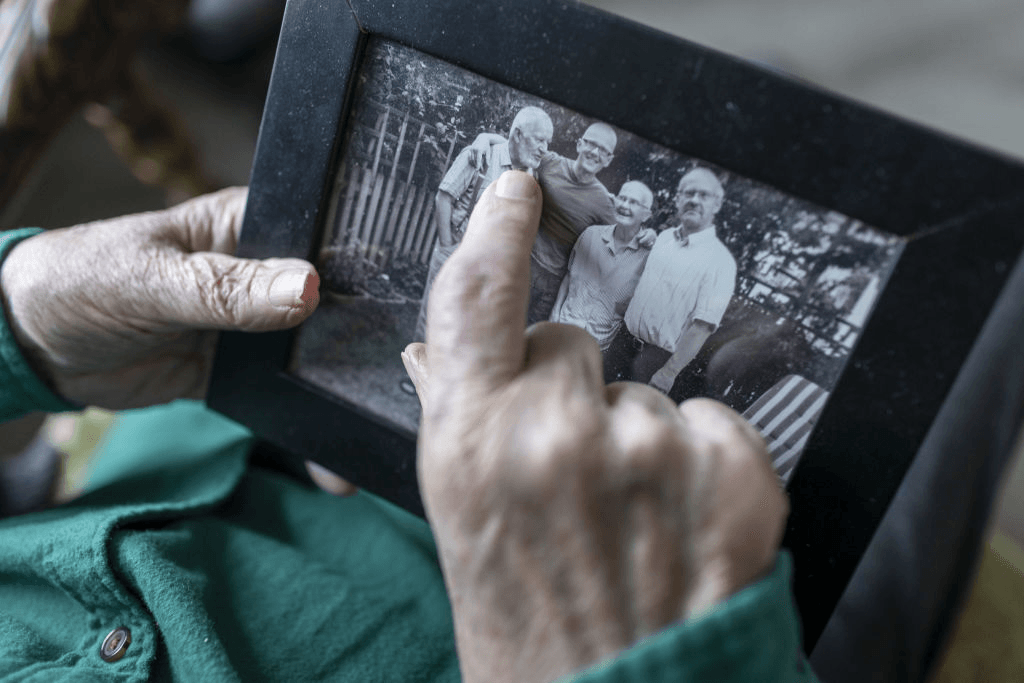

We know the answer to that question, for it drives so much of our higher animal psychology: or else, we die. The organism is always and forever bound to its state of precariousness, and eventually that precariousness must win. It always wins. To be alive is to be able to die.

Life is not a blender

This emphasis on death as the definition of life serves many roles and will be useful for many purposes. On a purely scientific level, it can help us understand which features of organisms and their organization to focus on. This is important for the Templeton project I am beginning, because it sharpens our focus on how information can serve to keep an organism viable, i.e. self-maintaining.

On a philosophical level, the focus on death reveals a key problem with reductionist descriptions of life that rely on what is called the machine metaphor. For reductionists, life is nothing but a set of molecular mechanisms. We are therefore nothing but biochemical machines. This is a fundamental mistake, because while a machine can be switched off, there can be no “off” button for life. Even seeds that remain dormant for years are not “off” like my blender is off when I am not using it. Life is not a machine.

Finally, understanding life as what can die has a personal or even spiritual valence. It gives the lie to the strange transhumanist, techno-religious fantasy about conquering death. While I am all for extending my life if I can, I would never think to avoid its end. Instead, what I long for is the fullest experience I can muster out of this strange trip. Then when death does come, I will greet it like the old friend it has always been.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!