Mexico isn’t the only country which sets a date with the dead.

Around the world, different countries, cultures, and religions have unique relationships with their dead. And yet, there are plenty of festivals of the dead—which take place over the course of days, or even months—that share spookily similar rituals. Think: offering food, cleaning tombstones, and thanking deceased loved ones for their care and guidance. Don’t let shared origin stories diminish the importance and significance of each one though—they’re all as fascinating as the last.

Hungry Ghost Festival

WHERE: China

China’s Hungry Ghost Festival—which has the best name I think I’ve ever heard—is actually a Hungry Ghost Month. In fact, only the final day of the month, when the boundary between life and death is most blurred, is known as the Hungry Ghost Festival, and Chinese Taoists and Buddhists mark the solemn occasion by burning a lot of paper. Not only do they burn paper offerings—which signify the things living relatives wish to send to their deceased loved ones in the afterlife—they also release paper lanterns to help guide the spirits home.

Obon Festival

WHERE: Japan

The Obon (or just Bon) Festival is another Buddhist affair, and the Japanese equivalent of China’s Hungry Ghost celebrations (both take place on the fifteenth day of the seventh lunar month). However, the Japanese version is now usually celebrated on a fixed rather than fluctuating date, around mid-August. Depending where you are in Japan, you might see dances (like the Bon Odori), the release of floating lanterns, or bonfires marking the occasion, although visiting graveyards is a common countrywide ritual.

Chuseok

WHERE: North and South Korea

Unlike China and Japan, the Koreas honor their ancestors in the eighth lunar calendar month (roughly September/ October), in a celebration which also combines dance, food and general revelry over three days. The food, especially rice cakes called songpyeon, plays an important role, principally because thanks are also given to the deceased for their role in providing a good harvest. However, like other days of the dead around the world, graves are also cleaned and dances are also danced.

Samhain

WHERE: Celtic Peoples

Before Halloween (or All Hallows Eve) there was Samhain (or All Hallows), a Celtic tradition that admittedly has much in common with our present-day October 31 rituals. Take our fancy dress tendencies and giving of sweets for example. The day before Samhain, people thought that their ancestors returned from the afterlife to essentially press a giant reset button on the land and leave it empty just in time for winter. As a result, the night before (a.k.a. Halloween), they’d wear masks to blend in and leave food out for the returning souls. Sounds familiar, right?

Fiesta de las Ñatitas

WHERE: Bolivia

La Paz, Bolivia welcomes an unusual day of the dead ritual each November, as the Aymara people head to the central cemetery with their deceased loved ones’ skulls in tow. Displayed in boxes, and often adorned with flowers, the skulls are also given offerings (think: food and drink) in thanks for having watched out for their relatives from the realm of the dead over the course of the past year.

Gai Jatra

WHERE: Nepal

To catch a glimpse of the Nepalese Festival of the Cows (otherwise known as Gai Jatra), head to Kathmandu in August or September, where the eight-day affair is principally celebrated. Confused as to what a Festival of the Cows has to do with celebrating the dead? Cows are thought to help guide the deceased into the afterlife, so families with a recently departed loved one will guide a cow (or a boy dressed as a cow) through the streets to both honor and aid their deceased.

Qingming (a.k.a. Ancestors’ Day)

WHERE: China

Cleaning the tombs of the deceased forms a large part of China’s Ancestors’ or Tomb Sweeping Day, although consuming dumplings and flying kites are also important. Similarly, offering goods of value in the afterlife—such as tea and joss sticks—is also practiced on Qingming. It’s said that this memorial to the dead, which takes place in roughly mid-April, was established as a way to limit the previously overly-extravagant and all-too-regular ceremonies held in memory of the deceased.

Pchum Ben

WHERE: Cambodia

Pchum Ben, a 15-day-long ritual when the veil between living and dead realms is considered to be at its flimsiest, is celebrated countrywide in Cambodia. While the first 14 days, known as Kan Ben, are about remembrance, the fifteenth day—or, Pchum Ben Day—is when Cambodians gather en masse to celebrate. And, as with other festivals of the dead, food is offered to the souls of the departed, who it’s thought return to earth to both connect with their loved ones and atone for past sins.

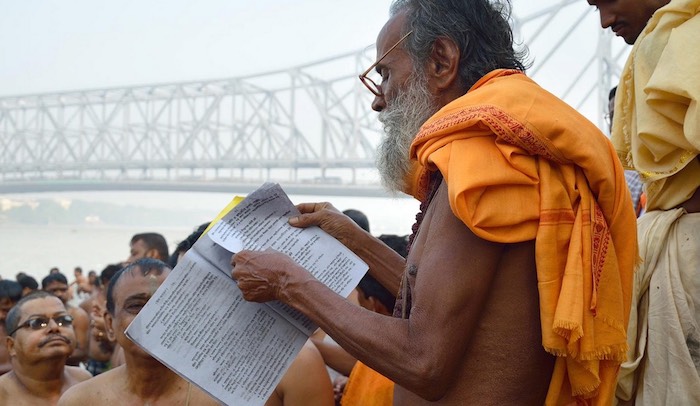

Pitru Paksha

WHERE: Hindus around the world

Undefined by geographical bounds, Pitru Paksha is a Hindu festival which, like that of the Cambodian Pchum Ben, centers on praying and providing food for the deceased. However, Pitru Paksha lasts for 16, rather than 15 days, and those who take part apparently shouldn’t undertake new projects, remove hair, or eat garlic for the duration.

Radonitsa

WHERE: Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine

Radonitsa, the Russian Orthodox Church’s second-Tuesday-of-Easter memorial for the departed, stemmed out of a Slavic tradition which involved visiting graveyards and feasting with the dead. Nowadays, the rituals remain remarkably intact, as this joyful remembrance involves leaving Easter eggs on the tombstones of the deceased before dining beside them, as well as sometimes gifting presents to your in-laws.

Totensonntag

WHERE: Germany

For German Protestants, Totensonntag (a.k.a. Sunday of the Dead) is considered a day of remembrance, on which those who honor the occasion will typically pay a visit to the graves of their deceased loved ones. However, unlike some of the festivals of the dead mentioned so far, Totensonntag is a far more somber affair. In fact, it’s sometimes known as “Silent Day” and it’s actually forbidden to dance and play music in public in some parts.

Tiwah

WHERE: Indonesia

The beliefs of the Dayak Ngaju people of Central Kalimantan, Indonesia state that after death and the departure of a person’s soul, their body’s spirit remains on earth. In order to liberate that spirit and ensure they ascend to the highest level of heaven, it’s necessary to conduct a tiwah. Held anywhere from some months to years after a loved one is buried, the tiwah involves the exhumation and purification of bones and can be a prolonged event in which multiple families participate.

Thursday of the Dead

WHERE: The Levant

In the Levant—a historical geographic region which includes many modern day, Eastern Mediterranean countries—Thursday of the Dead (sometimes known as Thursday of Secrets, Eggs or Sweetness) brings together Christian and Muslim traditions to honor the souls of the deceased around the Easter period. Typically celebrated in the morning, sweets and breads are traditionally doled out to children and those in need.

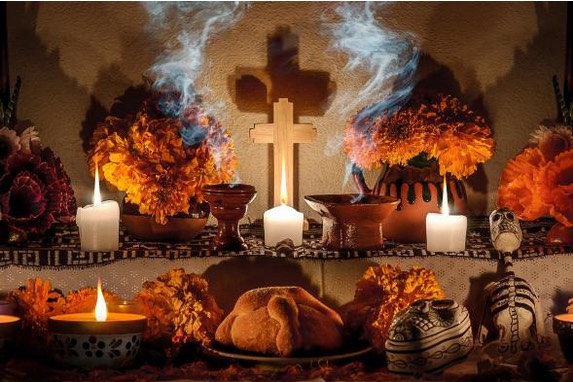

Día de Muertos

WHERE: Mexico and wider Latin America

You can’t talk about global festivals of the dead without throwing in at least a few references to Mexico and wider Latin America’s Día de Muertos festivities. On November 1 (Día de los Angelitos) and 2 (Día de Muertos), people from across Mexico pay homage to and celebrate the lives of their deceased loved ones by building altars and displaying sugar skulls, amongst other things. In Guatemala, giant kites are flown, while in Ecuador, the Kichwa people memorialize their deceased loved ones by visiting, cleaning, and eating at their gravesides.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!