Natural burial is challenging cemetery design and our increasingly toxic death management practices, while also finding potential for new expressions of thoughtfulness and beauty along the way.

By Foreground

In the 19th century, new cemeteries were designed for more than the dignified internment of departed loved ones. The landscape or garden cemetery provided much needed green open space for increasingly crowded cities. Cemeteries were the first public parks, where people came to picnic, relax and court. The pressure of today’s growing and diversifying populations and expanding cities are, again, challenging cemetery design, as well as burial practices. But as well as century-old concerns regarding space and the potential health risks of living close to overcrowded urban burial grounds, a new raft of threats are emerging. Modern burial practices have evolved to become highly toxic contributors to landscape contamination.

The world is increasingly concerned with environmental degradation, yet funeral practices have been largely overlooked until recently. In the mid-1990s, the National Centre for Groundwater Research and Training at the University of Technology, Sydney, examined nine cemeteries and crematoria around Australia. It found the biggest problem with these facilities was the potential for contamination from infiltrating stormwater carrying toxins from caskets and bodies to the underlying water table. But it took another decade for significant wide-ranging studies to emerge. The UK’s Environment Agency 2004 report into potential groundwater pollutants from cemeteries considers many factors leading to soil and groundwater contamination from human burial, including the organic and inorganic matter of bodies, coffins and other non-body grave contents.

Cemeteries are among the most toxic of modern landscapes in both their immediate and ongoing environmental impacts and intensive use of resources. The 2014 documentary A Will for the Woods outlines the problem of a typical American-style funeral, citing the toxic, resource-intensive materials of caskets that have become common in much of the world. “In the U.S. alone, approximately 33 million board feet of mostly virgin wood, 60,000 tons of steel, 1.6 million tons of reinforced concrete, and five million gallons of toxic embalming fluid are put into the ground every year.” They note further the large tracts of land and high maintenance of constant mowing, watering, and the application of chemicals.

Cremation is mistakenly thought to be more green. It actually releases considerable particulate pollution, CO2 (approximately 50 kilograms per cremation, on average), and toxins such as dioxins, furans, and mercury into the atmosphere.

Then there are a host of more modern elements such as mercury from dental fillings, pacemakers, esophageal tubes and other body implants which leach into groundwater once the body has decayed. Another significant pollutant emerged as people began to be buried with their mobile phones and other electronic devices. The trend was noticed in the United States when batteries started exploding during cremations.

Various environmentally-friendly techniques are being explored to dispose of bodies, including freeze-drying, shattering and dissolving. These offer significant space and land savings with minimal energy use and pollution compared with cremation. They also offer new, as yet unexplored, potentials for interment design and funeral landscaping.

A landscape history of burial grounds

Until a little over a century ago, cemeteries were located in churchyards or nearby. As churches were typically sited on high ground, there were few problems with leaching into groundwater or waterways. Still, overcrowding and the fact that urban graveyards were not always on elevated ground contributed to the potential for corpses to pollute groundwater, especially during epidemics of disease and plague, such as cholera and yellow fever. It wasn’t until Dr John Snow, one of the founding fathers of modern epidemiology, proved the vital connection between groundwater and the spread of disease that it was acknowledged. Snow’s famous map – an original type of infographic – of 13 public wells and clusters of cholera outbreak in London’s Soho in 1854 led to water testing that isolated the responsible bacterium. In 1924, Walter Bell wrote that he believed the lessons had still not been learnt from London’s Great Plague of 1664, when groundwater below “thickly buried” church grave yards contaminated the parish wells.

The mass-migration of rural workers to cities during the industrial revolution in Britain meant that new urban cemeteries were needed. However, so too was recreational open space. Long before Birkenhead Park inspired Frederick Law Olmsted’s Central Park in New York, landscaped cemetery-parks of Europe such as Pere Lachaise Cemetery, which opened in 1804 in Paris, quickly led to similar cemeteries in the United States. The same motivations to provide public parks for healthful recreation encouraged ‘rural’ cemeteries to provide a soothing, meditative natural environment and escape from urban crowding. Mount Auburn Cemetery near Boston, consecrated in 1831, was the first rural, or garden, cemetery in the United States and stills serves its dual role as sacred site and pleasure ground.

Olmsted worked closely at the Sanitary Commission with Montgomery Meigs, quartermaster general of the Union Army during the Civil War. Meigs sought Olmsted’s advice in landscaping cemeteries. Olmsted prophetically warned that the current fashion for elaborate and artificial gardening should be avoided because it would disappear and advised planting a sacred grove for the war dead using indigenous trees.

The pursuit of urban environments inclusive of the civilising influence of nature was a project that attempted to mitigate the pollution – literal and figurative – of the industrial city. A new and civilised urban landscape was proposed, whose open environment would contribute to “making the city more and more attractive as a place of residence”. There is something of this 19th-century ambition in 21st-century efforts to cleanse cities of contaminating influences. Both publicly- and privately-sponsored greening of city spaces can lead to the eviction of those some might consider undesirable.

More than half of all the cemeteries in the UK were constructed between 1851 and 1914, encompassing the initial emergence of multifunctional landscaped garden cemeteries, followed by the move to more efficient lawn cemeteries. It is likely a much larger proportion were established in Australia during that same time and following the same fashions. Melbourne General Cemetery, opened in 1853, was Victoria’s first ‘modern’ cemetery, designed like a large public park covering 43 planted hectares with generous walking paths and scenic views.

Woodland Crematorium and Cemetery in Stockholm, designed by Erik Gunnar Asplund with Sigurd Lewerentz, is among the most famous and beautiful burial grounds in the world. Although the design evolved during the course of the project from 1915 to 1940, the tranquil, rolling landscape, devoid of graves, echoes some of the aspirations of natural burial grounds. MoMA has exhibited the architectural and landscape drawings of Asplund since 1978. The curators note of Woodlands that the designers wished to “communicate the importance of nature, to which all living things ultimately return”. In 1994, the Woodland Cemetery became one of the few works of 20th-century architecture to make UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

Despite recent concerns over the toxicity of modern burial practices, old cemeteries and burials still have potential to contribute to soil and groundwater toxicity. In particular, Civil War graves in the United States contain bodies that were embalmed with various unregulated secret formulas, laced with arsenic. Embalming was a growth industry during the Civil War era, being the best way to preserve bodies to be returned to distant loved ones. Arsenic does not degrade as bodies rot and so is deposited in the soil and eventually groundwater. It is a carcinogen associated with skin, lung, bladder and liver cancers, among other diseases and cognitive deficits in children.

Another emerging concern with older graves is rising groundwater levels and higher tides. As sea levels rise with global warming, this could lead to contaminated leaching in the near future. It is already having effects in vulnerable low-lying communities where cemeteries are among land urgently being protected.

Natural burials can mitigate, and perhaps eliminate, pollution

There are several reasons why natural burials – also termed green burials or green funerals, organic burials, woodland burials and bushland burials – are becoming more popular. However, a consistently strong motivation is to reduce environmental impacts, including direct toxic contamination of existing sites, and the protection of particular landscape ecologies. Natural burial can do this in several ways: digging shallowly without heavy earth-moving equipment, preparing the body without chemical preservatives or disinfectants, using a compostable coffin or shroud or none at all, avoiding burial of any other toxic or non-biodegradable items, having no headstone or high embodied-energy marker, and conducting any services including food, printing, transport, music and more and in a sustainable non-polluting, no- or low-energy way.

Landscape architect and academic Andy Clayden of the University of Sheffield, researches the planning, design and management of cemetery landscapes. He has led a team that co-authored the first book to review the history and past 20-year growth of natural burials: Natural Burial: Landscape, Practice and Experience, published in 2014. In a paper last year his team focused on the significant contributions of natural burial sites to ecosystem services in England. The ecological benefits are mirrored by shifting perceptions as “natural burial is transforming the traditional cemetery, with its focus on an intensively managed lawn aesthetic, towards a more habitat rich and spatially complex landscape with its own distinctive identity.” Coupled with an ethical-aesthetic shift in death management, this approach is opening many areas of potential engagement and exploration for designers across the full spectrum of services.

A number of organisations have emerged to variously support and oversee natural burials. The United Kingdom’s Natural Death Centre is the oldest, established in 1991 and offering support, advice and extensive links to information for the public. The Green Burial Council in North America, founded in 2005, offers certification as well as education and advocacy. Also established in 2005 is Canada’s Natural Burial Association, serving both the public and burial operators. In 2014 a diverse group of professionals in Australia founded the Natural Death Advocacy Network (NDAN) with a wide remit to advocate, as well as encourage discussion and conduct and disseminate research.

One important aspect of natural burials is the covering a body receives. A co-founder of NDAN and passionate advocate for natural burial, Dr Pia Interlandi, has researched the effects of clothing and textiles on decomposition. Her PhD involved rigorous immersion in the rituals associated with preparing the body for interment. Garments from this investigation have been exhibited at the London Science Museum and London Print Studio. In 2012, she started her current practice, Garments for the Grave, where she now designs custom-made biodegradable burial garments with client family participation.

Australian natural burial sites

Bushland or natural burial is possible in portions of many cemeteries throughout Australia, although there has been little attention given to their complex landscape design. Two years ago Burnie City Council looked to offer a dedicated natural burial site in Tasmania, acknowledging the rising interest in natural burials while, capitalising on the state’s clean, green image and natural scenery. Kemps Creek Cemetery, which includes the Sydney Natural Burial Park, claims to offer Sydney’s first eco-burial area. A different and popular service is being offered in the south-west of Victoria. Upright Burials opened in 2010 as Australia’s first vertical burial ground. As well as taking up much less space than conventional burial, the Kurweeton Road Cemetery adheres to many further environmentally-friendly processes such as an absence of any grave-markers. The exact location is GPS recorded and provided to family and friends. Queensland funeral directors advise of two ‘green’ burial sites within cemeteries both operated by local councils: one as part of the memorial gardens at Lismore in northern NSW and another, which is the state’s only registered green burial site, within Alberton Cemetery on the Gold Coast.

An award-winning master plan for Acacia Remembrance Sanctuary within Itaoui Woodland Park was the first of its type planned in Australia. Developed by landscape architects McGregor Coxall working with Chrofi, the project encompassed 10 hectares of degraded, yet protected bush ecology west of Sydney. The design philosophy looked to establish a model that would not only protect, but reinstate the flora and fauna of the site. It has considered ongoing maintenance as part of full environmental considerations, including having all energy requirements generated on site, on-site water treatment and reuse, and limited slashing of the indigenous grasslands to create pathways instead of introducing exotic grasses and regular mowing practices.

Aspect Studios were responsible for the design of 11 hectares of native gardens at Bunurong Memorial Park, which opened in 2016. Much like early garden cemeteries, the realised proposal caters for the wider community’s need for open space, accommodating weddings, funerals and fitness groups, as well as picnicking and play. Bunurong also includes a new natural burial area, Murrun Naroon.

Reconsidered design approaches for cemetery landscapes, both expanding and new, are clearly an important area of innovation that will curb land contamination. However, new building opportunities can also reset expectations. Harmer Architecture’s Atrium of Holy Angels Mausoleum in Fawkner Memorial Park north of Melbourne was a rare chance to interpret a very old form. The nature of mausolea help contain any contaminants by isolating bodies and congregating remains, which takes up less space and resources.

Despite the thorough, successful translocation of 19th-century British garden cemeteries, followed by equal enthusiasm for the shift to 20th-century lawn cemeteries, Australian researchers warned in 2011 that: “If the concept of green burials is to have any degree of success in Australia, burial operators, land managers and planning authorities cannot simply transplant the practices employed in North America or Europe into the Australian context.”

Perhaps a similar translation of considered species, ecology and aesthetics is needed, as was slowly adapted when Australian landscape gardeners and designers such as Edna Walling looked to the British ‘wild garden’ of William Robinson. The wilderness of Britain is not the wilderness of New South Wales or Victoria or the many smaller patches of ecologies that Walling became familiar with while documenting roadside vegetation and that changed her approach to landscape design.

If the natural burial movement is to achieve its fullest potential to enhance environments, rather than just refrain from harming them, designers should aim to serve both new sensitivities around death and memorialisation, as well as new sensitivities toward our threatened environments.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Czechs clean thousands of human bones in ossuary renovation

Restoration experts in the Czech Republic have been set an unusual task – to dismantle four towering pyramids made up of centuries-old bones from more than 40,000 human bodies, clean them up and then reconstruct them as before.

The restoration project, expected to last two years, is aimed at preserving the bones, the chief attraction at the Sedlec ossuary church, a site on the outskirts of the mediaeval mining town of Kutna Hora in the central Czech Republic.

The project also aims to restore and strengthen the church building which houses the bones and skulls.

The site, which draws half a million visitors every year, not only features the four large pyramids of bones – it also boasts a chandelier, a coat of arms and various other decorations made from every bone in the human body.

“Many people find it weird today and come to see this as some dark spectacle, a house of horrors,” said Radka Krejci, in charge of operations at the local parish.

“But we do not want it to be perceived like that, it is a place of reverence, a burial place.”

The bones came from a cemetery adjacent to a monastery founded by the Cistercian order in 1142.

The burial ground was enlarged during a plague epidemic in the 14th century. In 1318, about 30,000 people were buried here and more joined them in the 15th century during religious wars between Roman Catholics and the Hussites.

A lack of space prompted the decision to exhume the bones and place them in a depositary, one of a number of such sites around Europe, during the 16th century. Legend says that a half-blind monk built most of the bone structures.

The present appearance of the bone structures dates from 1870 and is the work of Czech wood-carver Frantisek Rint, who added the various decorations to the original pyramids.

The renovation is necessary due to the aging of both the bones and the ossuary.

“The bones will be cleansed of surface dirt and then soaked in lime solution. This is a natural method of preservation which was also used during the creation of these pyramids,” said conservation expert Tomas Kral.

To make sure the structures are rebuilt in the original format, the restoration team has hired a firm, Nase Historie, to produce computer models of the bone pyramids using photos and videomapping.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

At the end of her life, my mother started seeing ghosts, and it freaked me out

By Steven Petrow

Last summer, six months before my mother died, I walked into her bedroom, and she greeted me with tinny hello and a big smile. She then resumed a conversation with her mother – who had died in 1973.

“Where are you?” Mom asked, as though Grandma, a onetime Fifth Avenue milliner, was on one of her many European hat-buying junkets. As I stood there dumbstruck, Mom continued chatting – in a young girl’s voice, no less – for several more minutes. Was this a reaction to medication, a sign of advancing dementia? Or was she preparing to “transition” to wherever she was going next?

Regardless, Mom was freaking me out – as well as my brother, sister and father.

As it turned out, my mother’s chat with a ghost was a signal that the end was inching closer. Those who work with terminally ill people, such as social workers and hospice caregivers, call these episodes or visions a manifestation of what is called Nearing Death Awareness.

“They are very common among dying patients in hospice situations,” Rebecca Valla, a psychiatrist in Winston-Salem, N.C., who specializes in treating terminally ill patients, wrote in an email. “Those who are dying and seem to be in and out of this world and the ‘next’ one often find their deceased loved ones present, and they communicate with them. In many cases, the predeceased loved ones seem (to the dying person) to be aiding them in their ‘transition’ to the next world.”

While family members are often clueless about this phenomenon, at least at the outset, a small 2014 study of hospice patients concluded that “most participants” reported such visions and that as these people “approached death, comforting dreams/visions of the deceased became more prevalent.”

Jim May, a licensed clinical social worker in Durham, North Carolina, said that family members – and patients themselves – are frequently surprised by these deathbed visitors, often asking him to help them understand what is happening. “I really try to encourage people, whether it’s a near-death experience or a hallucination, to just go with the flow,” May explained after I told him about my mom’s visitations. “Whatever they are experiencing is real to them.”

Valla agreed, telling me what not to do: “Minimize, dismiss or, worse, pathologize these accounts, which is harmful and can be traumatic” to the dying person. In fact, May said, “most patients find the conversations to be comforting.”

That certainly appeared to be the case with my mother, who had happy exchanges with several good friends, who, like my grandmother, were no longer living.

In a moving 2015 TED talk, Christopher Kerr, the chief medical officer at the Center for Hospice and Palliative Care in Buffalo, showed a clip of one his terminally ill patients discussing her deathbed visions, which included her saying, “My mom and dad, my uncle, everybody I knew that was dead was there (by my side). I remember seeing every piece of their face.” She was lucid and present.

Since Mom had already been diagnosed with advanced dementia, I originally thought her talks were a sign of worsening illness. In fact, current research posits that a combination of physiological, pharmacological and psychological explanations may be at play. That’s exactly what May’s hands-on experience of more than 14 years revealed to him, too.

May acknowledged that it’s understandably “hard to have empirical evidence” for such episodes in patients, but that it’s important for family members and health professionals to figure out how to respond

Last fall, another visit to Mom raised the stakes. As before, she greeted me by name and spoke coherently for several minutes before she turned to the bookcase near her bed and began cooing to an imagined baby. I watched in astonishment as Mom gitchi-gitchi-goo-ed to an apparition she referred to as “her” baby.

“My baby is very sick,” she repeated, clearly deeply concerned about this apparition. “She’s very thirsty. She’s hungry. She’s crying. Can’t you do anything for her?”

I didn’t know what to do. Neither did my siblings or Dad. I had long stopped “correcting” Mom. A year earlier, Mom had regaled me with the story that my niece Anna had made a delicious dinner the night before and was at that very moment out doing errands. In fact, Anna was away at college; also, I’ve never seen her cook, and she doesn’t even have a driver’s license. But why contradict Mom’s vision of a perfect granddaughter?

Social worker May, when asked about these sorts of imaginings, put it this way: “Don’t argue, because an argument is not what they need.” I decided to go along with the “baby” story and told Mom I was going to take the baby to the kitchen to bottle-feed her, which alleviated the crisis.

As the fall days grew shorter, Mom’s “baby” was a continuing presence at my visits, with my mother becoming increasingly distressed. I would settle things down by giving the imagined infant an imaginary bottle, or cradle her in my arms and leave the room for a while, saying I was taking her to the doctor. At one point I asked gently, “Mom, do you think the baby is you?” She didn’t miss a beat. “Yes,” she replied. “The baby is hurting.”

In fact, the largest study to date on deathbed visions reported on numerous cases when the “arrival of … a visitor appeared to arouse anxiety and intensify death fear.”

But what to do? I hated that Mom’s level of distress was skyrocketing in what turned out to be her final weeks. I simply held Mom’s hands a bit tighter and tried to distract her as best I could with family and political news. Oh, and I cooked, which she loved my doing.

One evening I made a simple dinner: spaghetti with a store-bought marinara sauce and a bright green leafy salad. Mom had pretty much stopped eating by this point, which is common as the end draws near, but she made a show of trying her best with this repast for the two of us, plus my father. It was heartbreaking to watch her try to spear the pasta, but she managed several hearty mouthfuls, saving room for a scoop of Sealtest vanilla ice cream.

After dinner, I helped her back to bed, where she exclaimed: “How did you know?” “How did I know what?” I asked. “That was exactly how I wanted my funeral to be. You invited all my favorite people, and the food was just what I would have ordered.”

She was beaming. Six weeks later, she passed – and pasta and salad were on the menu at her service.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The Language of Grief

Why and when one should read “The Year of Magical Thinking.”

by Katie Shi

Joan Didion’s “The Year of Magical Thinking” is a thorough, painfully poignant exploration of grief. Didion constructs this memoir with the same clarity and precision she employed in the journalistic works that brought her to fame in the 1960s and 70s. She guides the reader through her year of “magical thinking” after the death of her husband, John Gregory Dunne. While the tone of her narration is objective, she indicates her route through the spiritual and fantastical by means of the vortex in her memories that always leads her back to her living husband and healthy child.

Didion picks apart the concepts of grief, mourning and death without skimming over any explanations. She describes the history of funerals, how modern society perceives sorrow as something shameful and prolonged grief as a form of self-pity. She goes through the literature of grief and relays Emily Post’s etiquette advice in times of bereavement. She learns the medical terms that doctors use regarding her daughter Quintana’s condition, which worsens after her husband’s death. And throughout that year, Didion returns repeatedly to the night Dunne slumps over at dinner, a movement so sudden that Didion initially registers it as a joke. “Life changes fast. Life changes in the instant,” she writes. “You sit down to dinner and life as you know it ends.”

Didion’s perspective is certainly privileged — one can sense it from the places she’s been and the people she knows — but as much as that might estrange the reader, she doesn’t emphasize those specific details. If her closest friends happen to be celebrities, or if her memories take place in glitzy cities, Didion only mentions these facts and moments for context before focusing on the topic at hand: her personal experience with grief, and mourning, and the warning signs she wishes she had heeded before her husband’s heart attack on Dec. 30, 2003. In the book, Didion practices the anthropological version of “magical thinking” — she doesn’t deviate from her usual life routine, and she preserves her husband’s belongings (and therefore his presence) in the house. She’s unwilling to donate Dunne’s shoes, for example, because if she did then he wouldn’t be able to wear them if he returned. There is always this irrational but pervasive hope that if she performs the correct actions enough times, then Dunne’s death could be reversed.

As Didion studies everything she can find that’s been written about grief — not just novels, poetry and rituals, but also medical papers, psych studies and etiquette handbooks — she teaches the readers what she discovers from this process. Gerard Manley Hopkin’s poetry, which Dunne had referenced several times after his brother had committed suicide, returns to Didion as a talisman: “I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day.” She describes, with her trademark clinical style, how grief repeatedly and relentlessly strikes. “Grief is different. Grief has no distance,” she writes. “Grief comes in waves, paroxysms, sudden apprehensions that weaken the knees and blind the eyes and obliterate the dailiness of life. Virtually everyone who has ever experienced grief mentions this phenomenon of ‘waves.’” She cites Eric Lindemann, chief of psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital in the 1940s, who had defined the phenomenon as “‘sensations of somatic distress occurring in waves lasting from twenty minutes to an hour at a time, a feeling of tightness in the throat, choking with shortness of breath … and an empty feeling in the abdomen, lack of muscular power, and an intensive subjective distress described as tension or mental pain.’” This is a sensation that I, when grief-stricken, have been all too familiar with, yet I was still shocked to see how accurately described the emotions are on paper.

Didion has another famous essay, “On Keeping a Notebook,” in which she details her personal writing habits. For her, keeping a notebook has always been about preserving memories, both real and invented. “Keepers of private notebooks are a different breed altogether,” she declares, “lonely and resistant rearrangers of things, anxious malcontents, children afflicted apparently at birth with some presentiment of loss.” The sheer amount of documentation present in “The Year of Magical Thinking” is incredible. She and Dunne had recorded everything in writing — planners, notebooks, marginalia, kitchen books, Microsoft Word documents, a box with memorable quotes from a three-year-old Quintana. Didion combs through these records of their shared life in an attempt, almost, to resurrect Dunne through text. This gives “The Year of Magical Thinking” the intimacy of published diaries that personal essays, in their formality, seem to lack.

“The Year of Magical Thinking” is a wonderful read, objectively, but it becomes a necessary one for those who have experienced devastating loss themselves. Didion voices precisely what it feels like to lose what was once most important to the reader. When I suffered a great deal of personal loss, I experienced the same kind of magical thinking as Didion’s. At the time I kept wondering, what do I do with my life when there’s now a giant hole made freshly in the center of it, exposing my most vulnerable self to the rest of the world? How do I navigate the incident just before the loss occurred; how do I stop myself from returning to it over and over again? Didion didn’t give me answers, but she gave me her rapport, which turned out to be what I needed. This book gives the most to those who are in the process of grieving, offering not closure (“I realize as I write this that I do not want to finish this account,” Didion says) but an exploration of an experience the bereaved alone feel.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

How we can truly support those facing death or grieving over loss

By Dr. Nick Busing

Living well and dying well are what we all hope for. As we face dying and death, we need all the support we can get. It comes from many places, but we all know about the challenges associated with crowded emergency departments, the wait for hospital beds, the inadequate number of community placements, the stress on home care, the shortage of personal support workers … the list goes on.

Most Canadians (75 per cent in recent surveys) want to die at home, but most cannot. Most palliative care today is still provided in the hospital. The reasons are complex and include the lack of adequate home care palliative services and the limited support available to families and caregivers as they struggle to support a loved one at home. Conversations about dying and death are often left too late, when families and friends are in a state of panic, and are unsure what to do, and therefore turn to the local hospital to help them out.

In my more than 40 years as a family doctor, I learned so much from my patients and their families. When I provided end-of-life care in the home, I often noted the critical role of the family and friends in providing support and care to the dying person. Those families who spoke to the dying person well before the last days to understand the values, wishes and beliefs that were important, coped better, as I am sure the patient did as well. This reinforced for me that dying, death, care-giving and loss are social problems with medical aspects and not medical problems with social aspects.

We need to mobilize our communities (person by person, street by street, neighbourhood by neighbourhood) to become better able to support each other as we age. Compassionate Ottawa, a grassroots organization, only two years old, lives by the following vision: A compassionate Ottawa supports and empowers individuals, their families and their communities throughout life for dying and grieving well.Compassionate Ottawa was started by volunteers, and is sustained by volunteers, all of whom want to help our community normalize discussions about dying, death and grieving so that we can reach out to each other to provide support when needed.

The compassionate city movement was started in the United Kingdom and advocates for the role of the community in providing support and care. The long-term goal for us is to achieve a new model of care for those dealing with dying, death and grieving. Compassionate Ottawa is working with schools, workplaces and faith organizations to educate them about planning for dying and death so that they foster resiliency at the individual level. We are conducting advance care planning (ACP) workshops with many community groups. Our compassionate city strives to be one that recognizes that caring for each other should not be left to the health and social services but is the responsibility of all of us.

Amongst its initiatives, Compassionate Ottawa is proud to bring the HELP project (Healthy End of Life Project) to Canada from its origins in Australia. This three-year research project, with funding from the Mach-Gaensslen Foundation of Canada and led by researchers at Carleton University, will work with two faith groups and two community health centres in Ottawa to develop the skills and confidence to offer, ask for and accept help near the end of life. We will identify the challenges and successes we encounter and hope to have lessons that will be of use not only in Ottawa but also in communities across Canada.

We cannot continue to look only to the government’s health and social services to support our friends and relatives as they near the end of their lives. A push for more resiliency in the community would be a great benefit to all of us. And downstream it would mean fewer visits to the emergency rooms, fewer admissions to hospital, less demand for experts, less costly care and, hopefully, a more satisfied and stronger population.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Love at the end of life

By Maryse Zeidler

Meaghan Jackson has a surprising amount of insight into death and love for a 36-year-old.

“Working here, it’s changed me,” Jackson said from a wood-panelled room at the North Shore Hospice, where she has worked as a music therapist for four years.

“It’s completely changed the trajectory of my life.”

Jackson guides the residents at the hospice through their final days. She helps them write songs for their loved ones, and plays music for them as they take their last breaths.

Jackson has worked in “death and dying” since she was 22. She says her experiences prompted her to have children early in life, and focus on the present, no matter how difficult.

“I practice the art of being present when that present isn’t pleasant,” she said.

Health practitioners like Jackson say their experiences working with dying patients offer insights into love, relationships and how to focus on what matters.

Each of the four practitioners interviewed for this story — a doctor, a social worker, a nurse and a music therapist — say dying patients tend to focus their energy and attention on the people they love.

Dr. Pippa Hawley, a palliative care doctor at the B.C. Cancer Centre, says she has seen couples and families reconcile after decades apart. She’s also seen several of her dying patients get married in the palliative care unit, sometimes in their beds.

Hawley says dying patients don’t have time to take loved ones for granted.

“All of that stuff that we bother with on a day-to-day basis just fades into irrelevancy,” she says.

Dying patients face many challenges with their partners, even when they prioritize love.

Melanie McDonald, a social worker who also works in palliative care at the B.C. Cancer Centre, says every couple she helps deals with death differently.

Couples who thrive during difficult moments are often those who can balance sadness with joy and love, she says.

Nurse Jane Webley, who leads Vancouver Coastal Health’s palliative care unit, says the strongest couples are best at honestly communicating their needs, feelings and end-of-life plans.

Webley says patients who find it too difficult to discuss those matters are often the same ones who push loved ones away and face death alone.

“I think that’s a protection mechanism,” she said. “I would say 90 per cent of the time, it’s fear — and that fear is brought about by lack of communication.”

Dr. Hawley says some of her patients are never able to communicate their feelings and needs. Often, she says, that’s been a long-standing issue for them.

“People tend to die as they have lived,” she said.

Talking about death and end-of-life plans is often easier for older couples who are often more in touch with mortality. But Webley says it’s never too soon to have those difficult conversations.

Another challenge couples face when one is dying is learning to give or receive help, health practitioners say.

Social worker McDonald says people who aren’t used to being caregivers, typically men, often struggle when they’re suddenly thrust into that position. But most people learn to take on that role, she says.

Dr. Hawley says patients can face problems as they lose their independence. But she says it’s important for people to let their partners care for them.

“Don’t feel like you’re a burden,” she said. “It’s actually a wonderful gift to be allowed to care for somebody, to show them that you love them.”

All four of the health care practitioners say love at the end of life can take many shapes.

“Love looks differently in different situations,” says social worker McDonald. “Love shows up in the end of life in friendship and in families and pets and faith traditions and all sorts of different ways.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

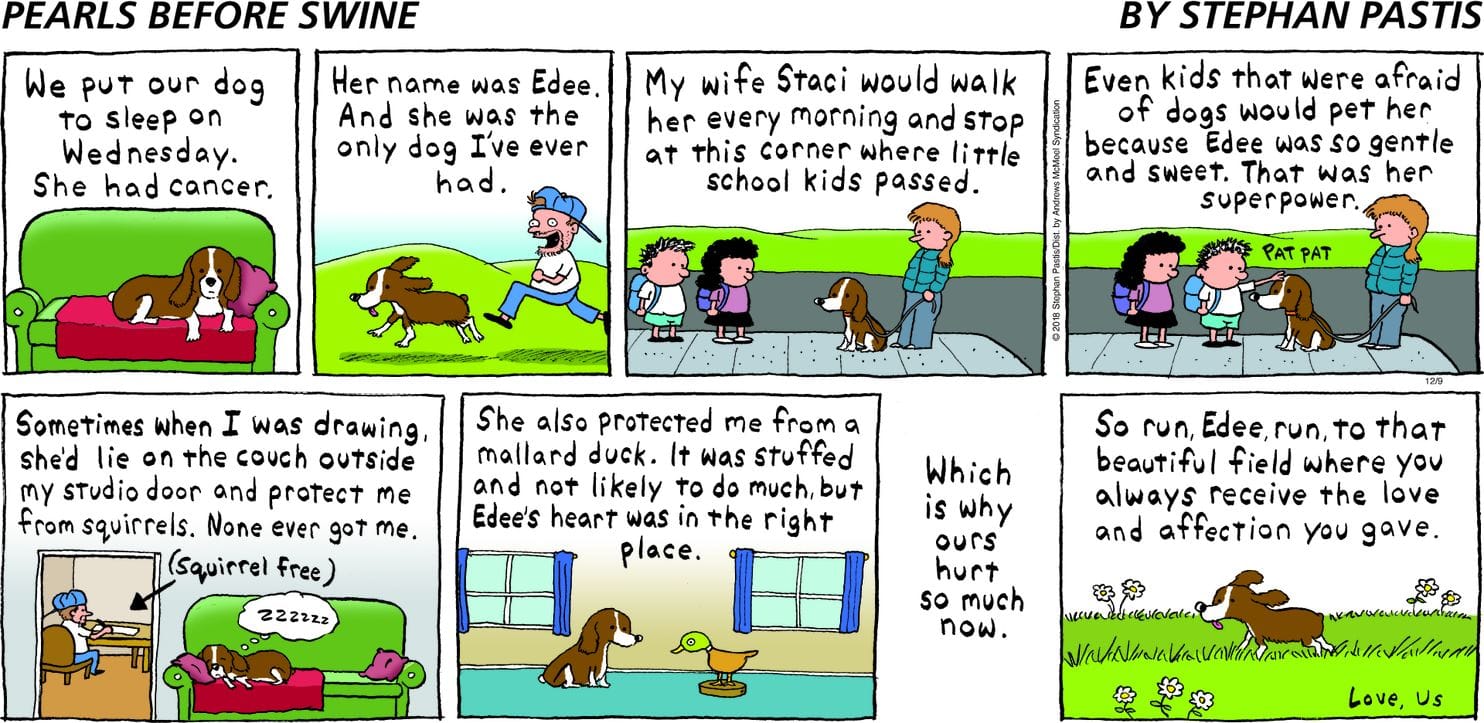

A cartoonist drew a touching tribute to his dying dog.

His readers gave him an outpouring of sympathy.

Stephan Pastis ducked into an Arizona coffeehouse last September and began to grieve. He sketched and cried as he wrote the words, “We put our dog to sleep on Wednesday.” The plot twist was, about 800 miles away, Pastis’s dog was still alive, though her time drew near.

Edee, a loving and gentle springer spaniel, was the only dog Pastis had ever had. Now here he was, a cartoonist who uses drawing as a coping technique, on a personal trip far from his Northern California home, unable to comfort Edee and say goodbye to her one last time before she was put down.

The resulting art was not the sort of sentiment that readers usually expect from Pastis, a former lawyer. As the creator of the popular comic “Pearls Before Swine,” he entertains millions of fans by often trafficking in darker and snarkier human emotions, as channeled through a gallery of animal characters, including the self-serving Rat and the wide-eyed innocent Pig.

Although some comic-strip creators draw upon events from their personal lives for inspiration, most cartoonists don’t share their experiences directly through their work, free of fictive elements or filtering techniques. But on that emotional day in Phoenix — where Pastis was visiting his father, who has Alzheimer’s disease — the cartoonist decided to get as directly personal as an artist can get. “I’ve always run to my creativity to cope with life,” Pastis says.

So he wrote that Edee had cancer. He wrote that she was so sweet that “even kids that were afraid of dogs would pet her.” He wrote that she would “protect” him from squirrels and a stuffed mallard duck while he worked in his Santa Rosa studio. And he wrote of the “hurt” in the hearts of his family, including his wife, their 21-year-old son and 17-year-old daughter.

The punchline-free purity of that comic strip, published in December, struck a chord. Hundreds of readers contacted Pastis. And this week, his syndicate, Kansas City-based Andrews McMeel, announced that the Edee strip was its most buzzed-about comic of 2018, with nearly 500 comments and almost 1,200 “likes.”

That speaks, his syndicate says, to the power of going personal.

“It connects the readers to the comic at a whole different level,” says John Glynn, president and editorial director of Andrews McMeel Syndication. “It can, however, be jarring if the audience isn’t used to it.

“Stephan has done it well and regularly enough over the years,” Glynn continues, “that his readers know that they see a version of the cartoonist that you don’t see in most comics.”

A recurring character in “Pearls Before Swine” is an avatar of Pastis, comedically depicted as a beer-bellied, stubble-faced, overambitious and pun-happy hack whose work is insulted by the very characters he has created. But on occasion, Pastis the avatar will share an honest, true-life slice of himself.

When those genuine ideas come, Pastis says, he typically tries to draw them, even if he ultimately doesn’t publish them — because he doesn’t want to gum up the creative flow.

“When I sit down to write,” he says, “what’s there is there. When something tragic has happened” — from the death of a relative, say, to the enormity of a terrorist act — “the ideas seem to have a narrow spigot, and what’s there is something you have to get out — you have to write it.”

Last September, though, Pastis was feeling especially emotional. He had just come from being on set for a Disney film adaptation of his kids’ book series, “Timmy Failure.” Now here he was in Phoenix, where his father did not recognize him, and then his wife called to say that Edee would need to be put to sleep within hours to minimize the pet’s suffering — much sooner than they had expected.

“I was all by myself out there,” he says.

The cartoonist walked to the Lux Central cafe, pulled his ball cap down low and got lost in his art, listening to such mournful music as “To Build a Home” by the Cinematic Orchestra. He was trying to communicate through pictures both his love for his pet — he never had a dog as a boy and had come to fear dogs after once being bitten — and the degree to which Edee had become a part of the family over six years.

Edee was due to be put down at 11 a.m. Pastis finished drawing and headed to the Phoenix Art Museum — where he gazed at Frida Kahlo’s 1938 painting, “The Suicide of Dorothy Hale” — before calling his wife to hear how Edee’s final moments went.

Pastis had touched many readers in 2003, when he created a heart-wrenching comic after watching a news report about a bus attack in Jerusalem that killed six children. And the cartoonist got especially personal in 2012 when a poignant “Pearls” strip eulogized his father-in-law.

For Edee, Pastis let that creative spigot again flow.

“Sometimes when you write from the heart, in a moment like that, it has a way of distilling the essence of what is in you in a very straight, direct way,” Pastis says. “What comes out is sometimes pretty meaningful.”

When the strip ran Dec. 9, the immediate response was strong and uncommonly large, the cartoonist says. Many of the readers who contacted him had recently lost their pets.

Wrote one commenter on the syndicate’s GoComics.com site: “Your comic is really hard to read. I can tell because my eyes are starting to sweat.” Some readers offered thanks and condolences and spoke of a pet’s afterlife across “the Rainbow Bridge.” Another commenter said: “Sometimes the best comics are the sad ones.”

A comic strip like that, Pastis says, “provides a sort of release of emotion — it becomes this thing they can connect to.”

And comics have the ability, he continues, “to comment on your life in a way that helps you and the people around you.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!