By Gary Wasserman

My wife’s brother Rich died the last week in February. They were very close. Shortly after he passed, in the emergency room of a hospital in Washington state, his body came home. There it was wrapped in a Stewart tartan blanket (his family name) and placed on a table in a window alcove facing Mount Baker. He remained there for the next three days clad in a favorite red plaid Pendleton shirt, jeans, moccasins and a much-worn woolen cap, On the second day, his wife, Sharon, put binoculars around his neck, a reminder of his many hours watching the snow geese, hawks, trumpeter swans and bald eagles surrounding his beloved farm.

Sharon was connecting to a movement that had arisen in the 1990s for families to take back responsibility from hired professionals for the caring and mourning of loved ones in the privacy of their homes. It turns out to be an old American tradition.

Before the Civil War, funerals were a family affair. With help from their church and community, family members would wash, display the body and dig the grave for their dead. But, as Civil War historian Drew Gilpin Faust writes in her book “This Republic of Suffering,” the huge numbers of young men dying in the war far from home overwhelmed the personal home funeral. Instead, there was embalming, mass-marketed coffins and transporting bodies long distances. President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, followed by the public display of his embalmed body, became a major moment in the national marketing of this new death trade.

By the 20th century, undertakers were elevated to a professional class of funeral directors, bodies were seen as a risk to public health and the false narrative spread that families no longer had the right to care for their own. The practice of dying at home and family caring for the dead remained common only in rural areas.

Like most of us, Rich and Sharon hadn’t planned their funeral. Unlike us, they had talked and read about death, and attended a class on alternatives to standard funerals. These included arrangements for green burials, where bodies in the ground decompose in compostable caskets. Sharon also had talked with a friend who, with the help of a local home funeral group, had kept her husband’s body at home for three days for visits and prayers.

Rich’s death had been unexpected. A retired ophthalmologist, he had recently been diagnosed with prostate cancer and had his first chemotherapy treatment the week before. He developed sepsis, which can happen after chemo, and died the following day. He was 77.

Sepsis is fast-moving and deadly. Here are the symptoms to recognize

At the hospital’s ER, Sharon explained to two chaplains who sat with her that she wanted to bring Rich home. They put her in touch with A Sacred Moment, a local funeral home that is part of a national network reviving and supporting family-managed funerals.

A “very kind” man, as Sharon put it, from the group took the body to the house in a van. He gave Sharon information on keeping it cold with packs of dry ice and instructions to replace them every 12 to 18 hours. Sharon and her daughter washed and clothed the body.

Rich had passed away at 11 a.m. and by 1 p.m. his body was home.

For the next three days family and friends came by to see Rich. Some talked to him; one shared the beat of an ancient drum; some read poems. Sharon thought that many friends wouldn’t have attended a funeral parlor for a restrained viewing in a limited time. Here they could arrive individually or as family, whenever they wanted, stay as long or little as they could, bring photos or food or prayers or babies or guitars.

Our son Daniel arrived in the middle of the night to sit alone with the uncle who helped raise him.

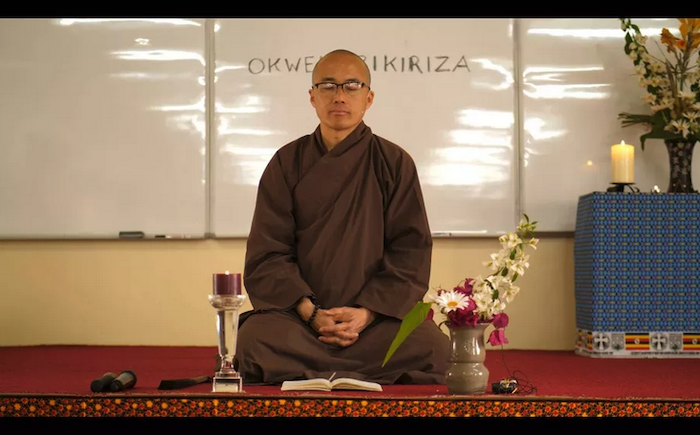

Sharon found it all incredibly comforting. Rich’s men’s support group of 30 years gathered for a morning of stories of kayaking in Alaska and tales of salmon fishing, hiking and climbing in the North Cascades. The second morning the couple’s Buddhist Sangha meditation group chanted, prayed together and held Sharon as they wept.

Many of the visitors seemed shocked that this was possible, that a body could be brought home for people to mourn however they wanted.

For family, it provided a last chance to talk with Rich, to be with him in a place he loved. Sharon remarked that so many people worried that they “never had a chance to say goodbye.” Now they could, and they didn’t have to look back and regret not saying the right thing.

In their own unplanned way, people could grieve.

At times there was a crowd, at others a solitary friend. A family member lit a vaporizer full of essential oils. Others placed flowers on his body. A table nearby had his notes written when he couldn’t talk because of mouth sores from the chemo and a guest book that soon filled with photos and letters and mementos.

Not everyone showed up — there were no solemn strangers in dark suits timing the starched formalities of yet another ceremony. Rich’s death was wrapped in the life that continued around it. Often there were kids playing, dogs wrestling, women cooking.

At 2 p.m. of the third day, the kindly man from A Sacred Moment returned to take the body. As they carried it out, Sharon played on the piano “It Had To Be You,” which she and Rich had often sung together. This time, she sang it with her daughter, Jo.

Washington state does not allow bodies to be buried outside a cemetery, so he was cremated and his ashes were scattered in his garden. A memorial service will be held when the tulips bloom in early spring.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

John, a Purple Heart–decorated World War II vet, had never been sick. Only in recent months had he developed some mild high blood pressure, for which his internist had prescribed chlorthalidone, a weak diuretic. Otherwise, his only medicine over the years was a preventive baby aspirin every day. With some convincing he agreed to be seen, so along with his wife and mine, we drove over to the local ER. The doctor there thought he might have had some kind of stroke, but a head CT didn’t show any abnormality. But then the bloodwork came back and showed, surprisingly, a critically low potassium level of 1.9 mEq/L—one of the lowest I’ve seen. It didn’t seem that the diuretic alone, which can cause less extreme reduction in potassium, could be the culprit. Nevertheless, John was admitted overnight just to get his potassium level restored by intravenous and oral supplement.

John, a Purple Heart–decorated World War II vet, had never been sick. Only in recent months had he developed some mild high blood pressure, for which his internist had prescribed chlorthalidone, a weak diuretic. Otherwise, his only medicine over the years was a preventive baby aspirin every day. With some convincing he agreed to be seen, so along with his wife and mine, we drove over to the local ER. The doctor there thought he might have had some kind of stroke, but a head CT didn’t show any abnormality. But then the bloodwork came back and showed, surprisingly, a critically low potassium level of 1.9 mEq/L—one of the lowest I’ve seen. It didn’t seem that the diuretic alone, which can cause less extreme reduction in potassium, could be the culprit. Nevertheless, John was admitted overnight just to get his potassium level restored by intravenous and oral supplement.