Tasked today with confirming and certifying deaths resulting from unnatural or unknown causes, coroners were officially introduced in England in 1194, primarily for the purpose of collecting taxes. But their early records of deaths that occurred in unusual or suspicious circumstances offer an incredible insight into daily life, attitudes and living conditions in the Middle Ages that we would not otherwise be privy to…

Here, Janine Bryant from the University of Birmingham, who has researched medieval coroners’ rolls of three English counties – Warwickshire, London and Bedfordshire – reveals some of the most intriguing causes of death…

1 Animals

Animals were responsible for numerous deaths in the medieval period.At Sherborne, Warwickshire in October 1394, a pig belonging to William Waller bit Robert Baron on the left elbow, causing his immediate death. Similarly, in London in May 1322 a sow wandered into a shop and mortally bit the head of one-month-old Johanna, daughter of Bernard de Irlaunde, who had been left alone in her cradle “at length”.

Cows appear to have been somewhat difficult to manage in the Middle Ages, and caused several deaths, including that of Henry Fremon at Amington, Warwickshire in July 1365. He was leading a calf next to water when it tossed him in and he drowned.

2 Drowning

People of all ages fell into wells, pits, ditches and rivers, and the coroners’ rolls of Warwickshire, London and Bedfordshire all record that drowning was responsible for the largest percentage of accidental deaths.

In August 1389 at Coventry, Johanna, daughter of John Appulton, was drawing water when she fell into the well. The incident was witnessed by a servant who ran to her aid, but while helping her fell in also. This was overheard by a third person who also went to their aid – he too fell in, and all three subsequently drowned.

3 Violence

While there are some regional and gender differences, approximately half of the entries in the medieval coroners’ rolls record violent deaths that occurred both within and outside of the home.

One domestic incident occurred at Houghton Regis, Bedfordshire in August 1276, when John Clarice was lying in bed with his wife, Joan, at the hour of midnight. “Madness took possession of him, and Joan, thinking he was seized by death, took a small scythe and cut his throat. She also took a bill-hook and struck him on the right side of the head so that his brain flowed forth and he immediately died”. Joan fled, seeking sanctuary in the local church, and later abjured the realm [swore an oath to leave the country forever].

Others deaths occurred in more mysterious circumstances: in Alvecote, Warwickshire in April 1366, Matilda, the daughter of John de Sheyle, was crossing some woods when she discovered an unknown teenage boy who had been feloniously killed and was found to have multiple wounds.

The rolls record that deaths frequently arose from disputes, and thus many seem to have been unpremeditated acts. The weapon often appeared to have been whatever was at hand, such as the case of Thomas de Routhe who died at Coventry in May 1355 after he was hit on the head with a stone.

4 Falls

There are many accounts of people who fell to their death, and they did so in a variety of ways: at Coventry in January 1389, Agnes Scryvein stood on a stool to cut down a wall candle. She fell off, landed on the stand for a yarn-winder, and ailed for two hours before eventually dying of her injuries.

At Aston, Warwickshire in October 1387, Richard Dousyng fell when a branch of the tree he had climbed broke. He landed on the ground, breaking his back, and died shortly after.

A London case occurred in January 1325 at around midnight when “John Toly rose naked from his bed and stood at a window 30 feet high to relieve himself towards the High Street. He accidentally fell headlong to the pavement, crushing his neck and other members, and thereupon died about cock-crow”.

5 Fun

The coroners’ rolls show that the Middle Ages weren’t all doom and gloom, and that people did actually have fun – although it occasionally ended in disaster.

At Elstow, Bedfordshire in May 1276, Osbert le Wuayl, “who was drunk and disgustingly over-fed” was returning home. “When he arrived at his house he had the falling sickness, fell upon a stone on the right side of his head, breaking the whole of his head and died by misadventure”. He was discovered the following morning when Agnes Ade of Elstow opened his door.

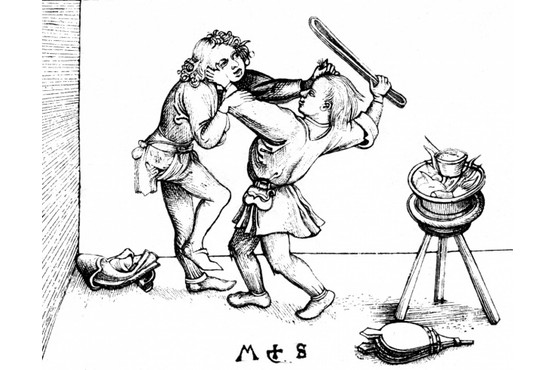

In Bramcote, Warwickshire in August 1366, John Beauchamp and John Cook were wrestling “without any malice or considered ill-will”. In the course of their game John Cook was tossed to the ground and died the following day from the injuries he sustained.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

What is a good death?

How my mother planned hers is a good road map for me.

By Cynthia Miller-Idriss

Years ago, I called my brother to ask whether he would serve as my health proxy, charged with making decisions about my care in the event of some unforeseeable disaster.

“Sure,” he said affably, and then added: “You should be mine, too. I mean, if I lost a leg or something, I wouldn’t want to live. You’d pull the plug, right?”

Unsettled by our widely disparate visions of a good life — and a good death — I quickly hung up and called my sister instead.

But more than a decade later, as we saw our mother succumb to the final stages of an indignant, drawn-out death from Alzheimer’s disease, I find myself returning to my brother’s words. I still find his view of a good life terribly narrow: If I lost a leg, I would certainly want to live. But I have also come to appreciate his utter certainty about what a good life — and a good death — looks like for him.

Most of us avoid thinking about death, which makes a good one harder to come by. Two-thirds of citizens in the United States do not have a living will. Although most Americans say they want to die at home, few make plans to do so, and half will die in hospitals or nursing homes instead — a situation Katy Butler, author of “The Art of Dying Well,” attributes in part to our “culture-wide denial of death.”

Specifying what a good death means is especially important for dementia patients, who will lose the ability to express their own wishes as the disease progresses. In the early stages, patients have time to reflect and clarify what they do and do not want to happen at the end of their lives. But these options dry up quickly in later stages.

This means that most families are left with a terrible series of guesses about both medical interventions and everyday care. Are patients still enjoying eating, or do they just open their mouths as a primitive reflex, as one expert put it, unconnected to the ability to know what to do with food? What kinds of extraordinary resuscitation measures would they want medical staff to undertake?

In the absence of prior directives, such considerations are estimates at best. As I sat beside her one recent morning, my mother repeatedly reached a shaky hand to her head, patting the side of her face. Puzzled, I leaned in.

“Does your head hurt?” I wondered. She moved her palm with painstaking slowness from her head to mine, cradling my cheek. “Are you in pain?” I asked. Her mouth parted, but no words came. My eyes welled. Is this the path to the good death she wanted?

I may never know the answer. But over time, I did learn how to help her have a better one. One afternoon, after she was frightened by the efforts of two nurses in her residential dementia care facility to lift her from a wheelchair, a quiet phrase slipped out of her mouth. “There you go,” she murmured calmly, just as she had for a thousand childhood skinned knees and bee stings. She was consoling herself, I realized, and teaching me how to do it at the same time.

I learned to read micro-expressions, interpreting small facial shifts for fear, anxiety or contentment. I discovered I could calm her breathing with touch: holding her hand or settling my hand on her leg. She would visibly relax if I made the shushing sounds so second-nature from the sleepless nights I’d rocked my own babies.

“It’s okay, love, you’re okay, I’m here, I love you,” I would murmur, patting her shoulder. She would sigh, and close her eyes.

Some of the path to her good death was luck. Michelle, another dementia resident, decided she was my mother’s nurse. She sat beside her constantly, holding her hand and tucking small morsels of coffeecake between her lips. Whenever I arrived, Michelle would spring up, give me a surprisingly fierce hug and offer her informed assessment of how my mother was doing. “I take care of her,” she told me repeatedly, stroking my mother’s cheek.

Other parts of her good death came through privilege. She was the last of a generation of teachers to retire with a significant pension, easing the substantial financial burden of 24-hour care. My father’s own secure retirement enabled him to care for her at home for years, and to spend hours with her every day after she moved into a residential care facility.

But her good death is also a result of planning. Having laid out her wishes with some precision, my mother was part of the minority of Americans with an advanced directive specific to dementia. This means that we knew she wanted comfort feeding, but no feeding tube. A DNR (do not resuscitate) order helped guard against unnecessary pain and suffering — the broken ribs common in elderly resuscitation attempts, for example — in case of a catastrophic event. In the end, her wishes were followed: there were no tubes and no machines.

Some indications suggest more Americans are starting to think about what a good death will look like.

There are initiatives to encourage people to talk about end-of-life care. The Death over Dinner movement suggests groups of friends host dinner parties to process how they feel about death. “How we want to die,” the movement’s website prompts, “represents the most important and costly conversation America isn’t having.” Indeed, advising people on how to die well may be the logical next step for a burgeoning wellness industry that has captivated the attention of a generation trying to live a better, more balanced life.

There is no way to know for certain whether my mother’s death was the good death she wanted. But her willingness to think it through left us with less guesswork than most — and provided a good map for me as I tried to figure it out.

I am not sure I could ask for anything more.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Dead, buried, and growing…

How human composting could be a game-changer for the funeral industry

Recompose, a Seattle-based firm is the first to have developed a system that is able to transform a body into soil in about a month. It has come into focus after the state of Washington signed a bill to legalize human composting on May 22.

Human composting sounds like a strange thing when you first hear about it and it is natural that a person will be having questions as to What is it? How is it possible and if it is viable?

In fact, most of these questions emerged soon after the state of Washington signed a bill to legalize human composting. It allows licensed facilities to offer natural organic reduction, which turns a body, mixed with substances such as wood chips and straw, into about two wheelbarrows’ worth of soil in a span of several weeks.

This brings us to Recompose, a Seattle-based company which promises to build the first urban “organic reduction” funeral home in the country. It announced that it opened its Series A round of financing and has raised $6.75 million from investors for this project.

Recompose, which is a public benefit corporation, developed a system that is able to transform a body into soil in about a month. The corporation raised a seed round of $693,000 in investments last year, which it used to prove how safe the process is via a research pilot, called The Recomposition Science Project, with Washington State University.

The corporation also used the seed money to complete the engineering of its patent-pending system and then advocated for legislation in the state which passed with broad bipartisan support in April this year. The natural organic reduction process, which is the contained and accelerated conversion of human remains into soil, was legalized in Washington state on May 22 for the disposition of human remains.

Recompose is currently preparing to open Recompose|SEATTLE, which will be the first facility in the world where the service will be offered to the public. The service has been touted as an alternative to burial and cremation, which at this time is the most popular form of disposition in the country. With Recompose’s new service being offered, it will avoid the waste and emissions of both methods.

It is also said to sequester carbon emissions which could make it a potential game changer for the funeral industry. A lifecycle assessment that compared death care options had estimated that around 1.4 metric tons of carbon will be saved per person if they choose to go with Recompose’s service. The need of the hour in this day and age is sustainable funerary practices as 10,000 Americans turn 65 on a daily basis.

Katrina Spade, Founder and CEO of Recompose, said: “People want an option that aligns with the way they’ve lived their lives. They care about climate change, and they want to leave a legacy that gives back to the earth.” The numbers also add up with 64% of US citizens showing interest in eco-friendly funeral options in 2015.

Aside from the environmental impact, Recompose has stressed intention and authenticity. It also has the aim of helping families “create meaningful rituals around the death of a loved one”. The company is planning to open and operate composting centers where families can gather and where the bodies will be transformed into soil. With tremendous savings in carbon emissions and land usage, the corporation addresses the increasing demands for green alternatives.

Recompose stated: “If every WA resident chose recomposition as their after-death preference, we would save over a 1/2 million metric tons of CO2 in just 10 years. That’s the equivalent of the energy required to power 54,000 homes for a year.”

Senator Jamie Pederson, who sponsored the bill, said: “What I think is remarkable is that this universal, human experience of death remains almost untouched by technology. In fact, the only two methods for disposition of human remains that are authorized in our statutes have been with us for thousands of years: burying a body or burning a body.”

A broad community of supporters has formed around Recompose and many residents in the state took part in grassroots action to help the bill get passed. Spade said that she was ecstatic about the response from the community. “I heard from one person in her 90’s who called her senators and told them to please hurry on up and vote yes,” she added.

The founder now looks toward a future where every death helps create healthy soil and heal the planet. Spade said: “We asked ourselves how we could use nature — which has totally perfected the life/death cycle — as a model for human death care. Why shouldn’t our deaths give back to the earth and reconnect us with the natural cycles? At the same time, we’re aiming to provide the ritual, to help people have a more direct and conscious experience around this really important event.”

“As hard as it can be, the end of one’s life is a profound moment — for ourselves and for the friends and families we leave behind.” Now that the bill has been passed in Washington State, the Department of Licensing is creating a regulatory structure for the new disposition option pioneered by Recompose.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The impossible case of assisted death for people with dementia

Is it too much to ask people to follow through on previously expressed wishes for assisted death? An expert report suggests it may well be.

When Canada legalized medically assisted death in 2016, the legislation excluded a trio of particularly difficult circumstances, committing to studying them in detail over the following two years. Those reports—on advance requests, mature minors and cases where a mental disorder is the sole diagnosis—were authored by three panels of eminent experts from a variety of disciplines, and in spite of the resolutely neutral and delicate language in the documents, they make for deeply compelling reading.

Of the three complex circumstances, it is advance requests—which would allow someone to set out terms for their medically assisted death, to be acted on at a future point when they no longer have decision-making capacity because of dementia, for example—that have drawn the greatest interest and agitation for change.

The working groups behind the reports were not asked for recommendations, but rather to provide detailed information on how other countries have grappled with these issues, what a modified Canadian law would need to take into account and how fields like ethics, philosophy, health care and sociology might help us puzzle through these issues.

And while they explicitly take no position on what the government should do, a close reading of the evidence the expert panel gathered makes it virtually impossible to imagine that advance requests for Canadians could exist and be acted upon.

That is not because the will isn’t there; many people with dementia or other illnesses that will eventually consume their cognitive capacity profoundly desire some sense of deliverance and control of their ending, for reasons that are easy to understand.

It is not because requiring help with every task of daily living, or being unable to communicate one’s thoughts or conjure up the names of loved ones is not a real form of suffering; for many people, that is just as intolerable as the spectre of a physically painful death.

And putting advance requests into practice doesn’t seem prohibitive because people who want them would be unsure about where to draw their line; indeed, that threshold is glaringly obvious for those to whom it matters most, and robust documentation and communication with health care providers and family members could provide much-needed clarity.

Rather, the reason it seems virtually impossible that Canada could have—and, crucially, use—advance requests is because it is simply too heavy a burden for those tasked with deciding when to follow through on the previously expressed wishes of the person before them, once that person can no longer meaningfully speak up for themselves.

“Evidence from international perspectives suggests there may be marked differences between stated opinion on hypothetical scenarios and actual practice,” the report notes. In other words, while people generally understand why others want advance requests and broadly support their availability, almost no one can bring themselves to act on them.

“It’s to be expected that these will be heavy decisions to be made, and I’m not sure that we would want them to be light, either,” says Jennifer Gibson, chair of the working group that examined advance requests for medical assistance in dying (MAID), and director of the University of Toronto Joint Centre for Bioethics.

Gibson’s group and the two other panels that examined MAID for mature minors and for people with a mental illness were chaired by former Supreme Court Justice Marie Deschamps and convened by the Council of Canadian Academies, a non-profit organization that “supports independent, science-based, authoritative expert assessments to inform public policy development.”

What is striking in reading the report on advance requests is how profound and deeply human it is, and how quickly the debate becomes almost dizzyingly existential—much more so even than the issue of assisted death in general. “There’s this human experience that we’re all sharing. We’re all in that together—that we are mortal, that we will die, that we will lose loved ones in our lifetime,” Gibson says. “That unavoidable vulnerability sort of encapsulates a lot of these policy and clinical and legal discussions that are unfolding.”

The report delves into concepts like the meaning of personal autonomy; how we care for those we love by shouldering the responsibility of making decisions when they no longer can; the concept of suffering and who defines it; how we weigh the interests of the patient against what their doctor and family are asked to handle; and which safeguards might help reassure those gathered at the bedside who have to make a decision.

“We can think about it as burden, but it’s not just about burden—it’s also about care….there is no question that burden is part of what comes with uncertainty. These are excruciating decisions that someone has to make on behalf of someone who is no longer decisionally capable,” says Benjamin Berger, a professor at Osgoode Hall Law School at York University and a member of the working group. “But a way of thinking about the burden is also, ‘Am I doing the right thing?’”

And a deeply conceptual sense of the self is central to the report: if in the present, you decide on and record a series of conditions under which you would no longer want to be alive, and you later become incapacitated, are your present and future selves the same person given how profoundly you’ve changed? If, once you are incapacitated, you appear perfectly content or even outright resistant to the MAID procedure you once requested, which version of you and which set of wishes and desires takes precedence, and why?

“Under what conditions might we expect that somebody would so radically lose those core compass points, if they lost capacity to make certain types of decisions, that they would become an entirely new person?” Gibson asks. “It is an existential question.”

And the report puzzles at length over this: can you really know from your present vantage point what your future self will want, how you might suffer or find joy in whatever your life looks like over the next horizon?

Research demonstrates that we are not very good at estimating what our quality of life would be if we fell ill or had some form of disability. This phenomenon, known as “the disability paradox,” is “pervasive,” the report notes. “The underestimation of quality of life by able-bodied or healthy people, rather than its overestimation by those living with a disability or chronic illness, drives the disability paradox,” the expert panel notes.

But again, in the debate over advance requests, this circles back to a deep concept of self: even if you are completely content once you are incapacitated, how much does that matter if your past, competent self loathed the notion of spending years in a long-term care facility needing help with every daily activity?

“Simply pointing to the idea that autonomy is respected and autonomy is important fails to wholly solve the most difficult issues in this field,” says Berger. “The question everybody is trying to ask is, understanding that autonomy is a core issue, what is the right method of ensuring that we respect autonomy?”

But for all of these sprawling legal, philosophical and ethical conundrums, it is when the report explores the experience of other jurisdictions with more experience practicing MAID or more liberal laws than Canada’s that the true difficulty in putting advance requests into practice for people with dementia becomes obvious.

Just four countries—Belgium, Colombia, Luxembourg and the Netherlands—allow advance requests for euthanasia in some form. However, “nearly all” of the information we have about advance requests in practice comes from the Netherlands, the report notes, because of “lack of implementation experience” in Colombia and Luxembourg, and very little detailed data available from Belgium.

The 2002 Dutch law that formally permitted the practice of euthanasia that had been going on for decades allowed for written advance requests for anyone aged 16 and older, in which they must clearly lay out what they consider unbearable suffering and when they would want euthanasia performed. Those would apply when people could no longer express their wishes and would have “the same status as an oral request made by a person with capacity,” the expert panel reports.

But while the annual reports from RTE, the regional review committees that govern euthanasia in the Netherlands, do not report the number of deaths due to advance requests, they do show that between 2002 and 2017, “all or most” of the patients who received euthanasia due to suffering from dementia were in the early stages of the disease and still had capacity to consent.

A study of 434 Dutch physicians between 2007 and 2008 found that while 110 had treated a patient with dementia who had an advance request, only three doctors had performed euthanasia in such a case (one doctor helped three people to die); all five of those patients too were “deemed competent and able to communicate their wishes.” The paper concluded that because doctors could not communicate with the patients otherwise, “Advance directives for euthanasia are never adhered to in the Netherlands in the case of people with advanced dementia, and their role in advance care planning and end-of-life care of people with advanced dementia is limited.”

Indeed, in 2017, a group of more than 460 Dutch geriatricians, psychiatrists and euthanasia specialists co-signed a public statement committing to never “provide a deadly injection to a person with advanced dementia on the basis of an advance request.”

And while family members of people with dementia support the idea of MAID if their loved one had an advance request, when it comes to acting on that, the majority—63 per cent in one study and 73 per cent in another—asked a doctor not to follow the request and actually provide euthanasia, but instead to simply forego life-sustaining treatment. “Some of the reasons given by relatives were that they were not ready for euthanasia, they did not feel the patient was suffering, and they could not ask for euthanasia when their loved one still had enjoyable moments,” the report explains.

Other Dutch studies show distinct contours in opinions on advance requests in cases of advanced dementia; the general public and family members of people with dementia view it more permissively than nurses and doctors, and doctors are most restrictive of all. “The authors of these studies hypothesized that this could be due to the different responsibilities of each group,” the working group wrote. “Physicians actually have to carry out a patient’s request, and when a patient cannot consent, this act comes with a heavy emotional burden.”

Here in Canada, the federal government has said it has no plans to alter the law to permit advance requests, even in the face of intense interest and pressure around the issue in a particular context a few months ago. In November, Audrey Parker, a vivacious Halifax woman with Stage 4 breast cancer, died by MAID two months earlier than she wanted to, because she feared cancer’s incursion into her brain might render her unable to provide final consent for the procedure if she waited. Parker spent her final months as the highly visible and compelling face of people like her, who are approved for MAID but forced to seek it earlier than they want to—or reduce badly needed pain medications—for fear they will lose the lucidity required to consent.

When it comes to concerns about determining when a patient with an advance request is ready for MAID, how clear their conditions are and whether they may have changed their mind if they can no longer communicate, the report suggest that cases like Parker’s would be the simplest and least controversial in which to permit advance requests. “These issues would likely not arise if a person wrote a request after they were already approved for MAID,” the working group notes. “In this case, they would be able to confirm their current desire for MAID themselves, and may even choose a date for the procedure.”

But when it comes to dementia—the condition which seems to inspire the strongest public desire for advance requests, and for which the disease trajectory is longer and more uncertain—the situation is much more difficult.

It is rarely useful to frame a public policy debate in terms of factions of winners and losers. But with the notion of advance requests for people with dementia, it is difficult to avoid the sense that in order for one group to get what it very understandably wants—a sense of control and escape from an existence that is at least as intolerable to some people as physical suffering—another group must shoulder a different sort of crushing burden—namely, the medical practitioners tasked with actually performing MAID and the family members or substitute decision makers who would have some role in sanctioning the procedure based on their loved one’s recorded wishes.

But Gibson argues that the solution to a heavy burden is not to make it light, but rather to ask what supports and measures would be required to bear it if such a thing were available in Canada. “And some members of the panel were really doubtful that anything would be sufficient to bridge those uncertainties, whereas others on the panel said, ‘I think we’ve got some experience with this, I think we could,’” she says. “There’s not going to be some external adjudicator to tell us we got it right.”

And while there is something distinctly fraught in decisions about MAID, she points out that families all over the country contend every day with life-and-death medical treatment decisions behalf of the people they love.

“It’s part of the ways in which we express love and caring for our loved ones, is we care for them even when they’re unable to care for themselves,” Gibson says. “We ought not to be surprised that these decisions are burdensome. And at the same time, they’re burdensome precisely because of these human connections that we have.”

The immense weight of these choices, then, is the price of admission for the bonds we share, and for the meaning we assign to life itself.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

End of Life Mitzvahs

by Rabbi Ron Isaacs

In recent months, I read a very powerful piece in The New York Times that detailed the last day in the life of President George H. W. Bush. It described how in the last week of the president’s life he had stopped eating and was mostly sleeping.

His longtime friend and colleague, James Baker visited him frequently in his last days, and was there when he passed away. Baker described how, at the end, he held Bush’s hand and rubbed his feet.

The former president died in his home, surrounded by several friends, family members, doctors and a minister. As the end neared, his son George W. Bush, also a former president, who was at his own home in Dallas, Texas, was put on speaker phone to say goodbye.

He told his father that he had been a “wonderful dad” and that he loved him. “I love you too,” Bush told his son. And those were his final words.

Bush’s doctor described how everyone present knelt around the president and placed their hands on him and prayed for him. It was a very graceful and gentle death, accompanied by loved ones who gathered in the intimacy of his home in Houston.

For almost four years now, I have been privileged to visit nursing homes, assisted living facilities and private homes to sing and play music for people in hospice under the title of my role as “Chords of Comfort.” I also make visits as a hospice chaplain.

On some days, my patients are alert and able to converse with me. On others, they lie in bed unable to speak and sometimes sleep.

On such occasions, I sit by their bedside and just keep them company. Sometimes a family member or two is present when I visit.

Several years ago when I arrived to visit a certain patient, I was surprised to find members of her family singing and playing guitar while the patient, who could not speak, moved her head rhythmically back and forth.

One of her youngest grandchildren had flown all the way from San Francisco, Calif. to New Jersey just to sing for her great grandmother. It was obvious that the singing and playing brought great comfort and pleasure to her.

When the family asked me to join in with my guitar, it became clear to me that we all were feeling spiritually uplifted by the beautiful music that we created together.

There is a rabbi who directs a Jewish-end-of-life care/hospice volunteer program. As part of his training program, the rabbi asks the volunteers to reflect on a moment when they were in need of someone to be present for them.

One man related the story of his bicycle accident when a stranger sat silently with him on the curb until the ambulance arrived. Another volunteer described how her grandmother sat knitting in the corner of the hospital’s delivery room throughout her three-day-long labor.

What both of these stories have in common is the power of someone simply being present for another person.

Chaplaincy – spiritual care – is all about accompanying another person while being fully present. It is all about trying to ensure that there will be times during the day when a patient is not left alone and has someone by their side.

Even when someone’s life is transitioning, healing of spirit is possible until the very last breath. It is especially at these times when our very presence can raise their spirits, which not only benefits them, but also us.

Being present and ensuring that no one is left alone is an incredible act of kindness and a supreme act of holiness. In the Jewish faith, it is considered a “mitzvah,” a religious obligation.

I hope that you will consider ways that you can help reduce isolation for those who are alone and provide them with “accompaniment.” Let us continue to find ways to be fully present for members of our own family and for those in the wider community who will benefit from our companionship and just “being there for them.”

Perhaps you may wish to consider committing to one specific act of accompaniment each month that will lift the heart and brighten the spirit of someone else – and probably do the same for us.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Tips for Helping Grieving Children

Doctors today have documented evidence to demonstrate that grieving can, in fact, make children sick. Health issues such as skin problems, cardiovascular disease and even cancer can often track their onset to a painful event translated as grief. Traumatic loss is so abhorrent to the mind that children often have difficulty coping. Children today have […]

Doctors today have documented evidence to demonstrate that grieving can, in fact, make children sick.

Health issues such as skin problems, cardiovascular disease and even cancer can often track their onset to a painful event translated as grief. Traumatic loss is so abhorrent to the mind that children often have difficulty coping.

Children today have numerous opportunities to distract themselves from grieving properly; i.e. video games, computers and television. In my book, The Only Way Out is Through, I share some insight into working through grief. Here are some tips for parents and caregivers to help children deal with grievances in a healthy manner.

Tips for Nurturing Bereaved Children

- Grieving children must get plenty of rest, eat a balanced diet and drink plenty of water. Exercise is also very important; however, remember that fatigue is often a characteristic of both loss and depression.

- Encourage a grieving child to express and vent shock, anger and fear. This will help the child stay connected to life and can re-establish trust in what has become an unsafe world.

- Children should be allowed to participate in the rituals of saying goodbye. This will give them a sense of realty and closure to this unthinkable event.

- Parents or caregivers of grief-stricken children should encourage their child to participate in weekly therapeutic groups with other children who have encountered the same kind of loss.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

A Graceful Exit: Taking Charge at the End of Life

How can we break the silence about what happens when we’re dying?

By

I was standing in my cubicle, a 24-year-old fact-checker envisioning a publishing career of glamor and greatness, suddenly shaking as I read the document my mother had mailed. It detailed her wish that I promise never to keep her or my father alive with artificial respirators, IV-drip nourishment, or anything else she deemed “extreme.”

I was horrified, and slightly angry. My mom was a 54-year-old literature professor who’d spent the 1970s eating whole grains and downing vitamins. She was healthier than anyone I knew. Why get so dramatic now? It seemed ghoulish, not to mention premature. But I scrawled my signature at the bottom of the page and shoved it into an envelope, my mother’s voice in my head, prodding me along.

As with the whole wheat and vitamins, my mother—back in 1990—was onto something long before it became conventional wisdom. But these days, Americans’ approach to aging and death is rapidly evolving, pushed both by the numbers and the grim reality behind them: In 40 years, 19 million Americans will be over 85, all at high risk of losing the ability to care for themselves or dwindling away because of organ failure, dementia, or chronic illness. (The days of a sudden fatal heart attack are fading; by 2008, the death rate from coronary heart disease was down 72 percent from what it was in 1950.)

So while many seniors now live vigorous lives well into their 80s, no one gets a free pass. Eating right and exercising may merely forestall an inevitable and ruinously expensive decline. By 2050, the cost of dementia care alone is projected to total more than $1 trillion.

My mom’s decision to face her end came not from any of these facts, but from the nightmare of watching her own mother’s angry decline in a New York nursing home. “You’re all a bunch of rotten apples,” Grandma growled at visitors, the words erupting from her otherwise mute lips. And there she sat for three years, waiting to die. “Why can’t you just get me some pills so I can go?” she would sometimes wail.

The slide toward death was only slightly less awful for my father’s mother. Grandma Ada would greet me with a dazed smile—though it was impossible to know whether she recognized the person standing in front of her wheelchair—before thrashing with involuntary spasms. An aide would come to restrain her, and then my dad and I would leave.

This cannot be right. This cannot be what we want for our parents—or ourselves.

In denial

Despite our myriad technological advances, the final stages of life in America still exist as a twilight purgatory where too many people simply suffer and wait, having lost all power to have any effect on the world or their place in it. No wonder we’re loathe to confront this. The Patient Self-Determination Act, passed in 1990, guarantees us the right to take some control over our final days by creating advance directives like the one my mother made me sign, yet fewer than 50 percent of patients have done so. This amazes me.

“We have a death taboo in our country,” says Barbara Coombs Lee, whose advocacy group, Compassion & Choices, pushed Washington and Oregon to pass laws allowing doctors to prescribe life-ending medication for the terminally ill. “Americans act as if death is optional. It’s all tied into a romance with technology, against accepting ourselves as mortal.”

For proof of this, consider that among venture capitalists the cutting edge is no longer computers, but life-extending technologies. Peter Thiel, the 45-year-old who started PayPal and was an early investor in Facebook, has thrown in with a $3.5 million bet on the famed anti-aging researcher Aubrey de Grey. And Thiel is no outlier. As of 2010, about 400 companies were working to reverse human aging.

Talking about death

The reason for this chronic avoidance of aging and death is not simply that American culture equals youth culture. It’s that we grow up trained to believe in self-determination—which is precisely what’s lost with our current approach to the process of dying. But what if every time you saw your doctor for a checkup, you’d have to answer a few basic questions about your wishes for the end of life? What if planning for those days became customary—a discussion of personal preferences—instead of paralyzing?

Dr. Peter Saul, a physician in Australia, endeavored to test this approach by interviewing hundreds of dying patients at Newcastle Hospital in Melbourne about the way they’d like to handle their lead-up to death—and how they felt discussing it. He was startled to find that 98 percent said they loved being asked. They appreciated the chance to think out loud on the subject. They thought it should be standard practice.

“Most people don’t want to be dead, but I think most people want to have some control over how their dying process proceeds,” Saul says in his widely viewed TED lecture “Let’s Talk About Dying.”

Nevertheless, when his study was complete, Newcastle went back to business as usual, studiously ignoring the elephant in the room, acting as if these patients would eventually stand up and walk out, whistling. “The cultural issue had reasserted itself,” Saul says drily.

Slow medicine

It’s hardly surprising that medical personnel would drive this reexamination of our final days. Coombs Lee, who spent 25 years as a nurse and physician’s assistant, considers her current advocacy work a form of atonement for the misery she visited on terminal patients in the past—forcing IV tubes into collapsed veins, cracking open ribs for heart resuscitation.

“I had one elderly patient who I resuscitated in the I.C.U., and he was livid,” she says. “He shook his fist at me, ‘Barbara, don’t you ever do that again!’ We made a deal that the next time it happened we would just keep him comfortable and let him go, and that’s what we did.”

It bears pointing out, however, that many doctors dislike discussing the ultimate question—whether patients should be allowed to choose their moment of death by legally obtaining life-ending medication. Several have told me that the debate over this overshadows more important conversations about how to give meaning to what remains of life. In Europe, the term of art is euthanasia—the practice of injecting patients with life-ending drugs—which remains illegal in the United States. But whatever the method, many physicians would prefer to avoid the entire topic.

“I don’t think euthanasia matters,” Saul says. “I think it’s a sideshow.”

While arguments flare around this, Dennis McCullough, a geriatrician in New Hampshire, has noticed a quieter answer taking shape among his own patients. Many are themselves retired doctors and nurses, and they have taken charge of their last days by carefully mulling the realities of aggressive medical intervention. Rather than grasping at every possible procedure to stave off the inevitable, they focus instead on accepting it. In place of scheduling never-ending doctor’s visits, they concentrate on connecting with others.

McCullough has termed their philosophy “slow medicine,” and his book about it, My Mother, Your Mother, is starting to attract attention around the world.

“If you go to a doctor to get a recommendation for having some procedure, that’s probably what’s going to happen. Doctors are driven by revenue,” he said in an interview. “But many of the things that we can do to older people don’t yield the results we’ve promised—medicine can’t fix everything. ‘Slow medicine’ is being more thoughtful about that and staying away from decisions based on fear.”

This attitude is gaining traction. In November, several hundred physicians plan to gather in Italy to discuss slow medicine (a name lifted from the similarly anti-tech slow food movement), and McCullough’s book is being translated into Korean and Japanese.

“What’s the last gift you’re going to give your family? In a sense, it’s knowing how to die,” he says. “Staying alive is not necessarily the goal.”

Death with dignity

I consider my mother-in-law, a practicing Catholic and right-leaning political moderate, a barometer for this slowly shifting national consciousness. She is in her mid-60s and healthy, but has already written directives specifying that Bach be played at her bedside and perfume scent the air, if her health deteriorates to the point where she cannot say so herself.

Personally, I’m relieved. Unlike my 24-year-old self, I now find it comforting to plan these things, rather than living in fear of them. But I would still be mired in denial were it not for former Washington Gov. Booth Gardner, whom I wrote about in 2008 when he was pushing for a Death with Dignity law and I was a newspaper reporter.

Shaking with Parkinson’s disease, he tried to spark conversation about legalizing physician-assisted aid-in-dying while attending a luncheon in downtown Seattle with a small circle of business friends: “I have a real tough time understanding why people like us, who’ve made tough decisions all their lives—buying, selling, hiring—do not have the right to make such a fundamental decision as this,” Gardner said, referencing his wish to take life-ending medication when his illness becomes unbearable, to gather his family and die when he chooses.

The men sipped their soup. They did not approve. They did not even want to discuss it. Yet that stony opposition—which mirrors the position of the Catholic church, groups representing the disabled, and hospice workers dedicated to maintaining “studied neutrality”—has, ironically, begun to nudge talk of death into the open.

Gardner, to my mind, had articulated the central concern: Wherever you come down on end-of-life decisions, the question is one of control—and who is going to have it over our bodies at the last moments.

Thus far, only Washington and Oregon have passed Death with Dignity laws, though a voter initiative is scheduled for the November election in Massachusetts. In Montana, the courts have ruled that physicians who prescribe life-ending medication for the terminally ill are not subject to homicide statutes; in New Mexico, two doctors have filed a suit challenging prohibitions against “assisting suicide.” And in Hawaii, four doctors willing to prescribe life-ending medication have geared up for a similar fight.

Yet after 15 years of legalized aid-in-dying in Oregon, the biggest news is how seldom people actually invoke this right. Since 1997, fewer than 600 terminal patients have swallowed doctor-prescribed drugs hastening their ends, though 935 had prescriptions written. Did 335 people change their minds at the last minute? Decide in their final days to cling to life as long as possible?

If so, that might be the best thing to come out of Compassion & Choices’ campaign: a peace of mind that allows us to soldier on, knowing we can control the manner of our death, even if we never choose to exercise that power.

My own immediate family ranges in age from 3 to 84, and I envision a dinner in the not-too-distant future when we will gather, talk about how to make my parents’ final journey as meaningful as all that has come before, and raise a glass to the next stage. Maybe at Thanksgiving.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!