When you die, do you want to be buried? Cremated?

How about being cryogenically frozen and then vibrated into tiny pieces? If you want to spend the hereafter in Kansas, you may eventually get the chance if legal and regulatory issues are resolved.

A new option called promession, the creation of a Swedish biologist, holds the potential to make burial more environmentally-friendly, its proponents say. A body effectively reduced to small particles and buried would turn to soil in a matter of months.

And while promession has yet to be tried on human remains—only pigs have so far had the privilege—the company pursuing the idea regards Kansas as fertile ground for the new method. So much so that the firm, Promessa, has one of its handful of U.S. representatives based in Overland Park. And a state lawmaker may introduce a bill in 2020 to clear the way.

In promession, the body is frozen using liquid nitrogen, then vibrated into particles. Water is removed from the particles, which are then freeze-dried. The remains are buried in a degradable coffin.

But in a legal opinion released just before Thanksgiving, Kansas Attorney General Derek Schmidt found that promession doesn’t meet the definition of cremation under Kansas law and regulation.

In cremation, the body is reduced to bone fragments and flesh is typically burned up by fire. In promession, both flesh and bone are reduced to particles. That difference is why the process does not legally count as cremation, according to Schmidt.

The decision was a surprise to Promessa representative Rachel Caldwell.

“We thought this would be no hang-ups whatsoever,” Caldwell said.

Interest has been growing in so-called green burials that minimize the environmental impact. A 2017 survey of more than 1,000 American adults 40 and older by the National Funeral Directors Association found 54 percent were interested in “green memorialization options” that could include biodegradable caskets and formaldehyde-free embalming.

“Newer, greener methods of burial, like promession, may help conserve resources and less pollution into the air or ground,” Zack Pistora, legislative director of the Kansas Sierra Club, said. “Why not rest in peace with peace of mind?”

Schmidt cautioned that a decision on whether promession is permissible under other state laws falls to the Kansas Board of Mortuary Arts. The board’s executive secretary didn’t respond to a request for comment Friday.

Caldwell said Kansas is the first state where she has sought a formal legal opinion because of what she views as the state’s relatively lax cremation laws. For example, Kansas doesn’t require fire to be used in cremation. That’s a helpful distinction because promession freezes bodies instead of burning them.

Caldwell asked her state representative, Overland Park Democrat Dave Benson, to seek the attorney general’s opinion. Benson said Friday he wasn’t surprised by Schmidt’s conclusions because in his experience attorneys general are hesitant to provide new interpretations of law.

Benson suggested he may draft a bill to authorize promession because of interest in alternatives to traditional burial or cremation. And because he’s taken “a little bit of a libertarian” view.

“If that’s what you want, hey, where’s the government’s interest in telling you not to?” Benson said.

Promession has gained attention over the past decade, often when news outlets mention it as an alternative to traditional burial or cremation, said its creator, Swedish biologist Susanne Wiigh-Mäsak.

Caldwell said she’s optimistic it could be used on a human body in the United States within five years. Promessa hears from people all over the world who want to undergo the procedure when they die, she said.

Still, it’s likely to take a long time to turn promession into a reality.

Jonathan Shorman covers Kansas politics and the Legislature for The Wichita Eagle and The Kansas City Star. He’s been covering politics for six years, first in Missouri and now in Kansas. He holds a journalism degree from the University of Kansas.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

‘Transhumanist’ eternal life?

No thanks, I’d rather learn not to fear death.

Herodotus, in the 5th century B.C., recorded an account of a race of people in northern Africa who, according to local lore, never seemed to age. Their secret, he wrote, was a fountain of youth in which they would bathe, emerging with “their flesh all glossy and sleek.” Legend has it that two millennia later, Spanish explorers searched for a similar restorative fountain off the coast of Florida.

We are still searching for the fountain of youth today. Instead of a fountain, however, it is a medical breakthrough, and instead of youth, we seek “transhumanism,” the secret to solving the problem of death by transcending ordinary physical and mental limitations. Many people believe this is possible. Observing a doubling of the average life span over the past century or so through science, people ask why another doubling is not possible. And if it is, whether there might be some “escape velocity” that could definitively end the aging of our cells while we also cure deadly diseases

Lest you think this concept is limited to snake-oil salesmen and science-fiction writers, the idea that aging is not inevitable is now in the mainstream of modern medical research at major institutions around the world. The journal Nature dubbed research from the University of California at Los Angeles a “hint that the body’s ‘biological age’ can be reversed.” According to reporting by Scientific American on research at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies: “Aging Is Reversible — at Least in Human Cells and Live Mice.”

The promise to end old age is exciting and mind-boggling, of course. But it raises a question: Why would we want to defeat old age and its lethal result? After all, as writer Susan Ertz wryly observed in her 1943 novel “Anger in the Sky,” “Millions long for immortality who don’t know what to do with themselves on a rainy Sunday afternoon.

Your boring Sundays notwithstanding, perhaps you think it’s obvious that getting old and dying are bad. “The idea of death, the fear of it, haunts the human animal like nothing else,” anthropologist Ernest Becker wrote in his 1973 book, “The Denial of Death.” Why else would we willingly put up with a medical system that seemingly will spend any sum to keep us alive for a few extra days or weeks?

It is strange that the most ordinary fact of life — its ending — would provoke such terror. Some chalk it up to what Cambridge University philosopher Stephen Cave calls the “mortality paradox” in his excellent 2012 book, “Immortality: The Quest to Live Forever and How It Drives Civilization.” While death is inevitable, it also seems impossible insofar as we cannot conceive of not existing. This creates an unresolvable, unbearable cognitive dissonance. Some have tried to resolve it with logic, such as the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus’ observation that “death, the most terrifying of ills, is nothing to us, since so long as we exist, death is not with us; but when death comes, then we do not exist.”

Transhumanism responds, “Whatever, let’s just avoid that whole second scenario.”

Another argument for transhumanism is less philosophical and more humanitarian. We think avoidable deaths are a tragedy, don’t we? Well, if most of the 27 million annual worldwide deaths of people age 70 and over could be somehow avoided, wouldn’t that put them in the category of “tragedy”? Shouldn’t we fight like crazy to avoid them?

While the transhumanism movement is making progress, it isn’t without its skeptics. Some don’t think it will ever work the way we want it to, because it asks science to turn back a natural process of aging that has an uncountable number of manifestations. Critics of anti-aging research envision any number of dystopian futures, in which we defeat many of the causes of death before very old age, leaving only the most ghastly and intractable — but not directly lethal — maladies.

Imagine making it possible to cure or treat most communicable diseases and many conditions and cancers that were once a death sentence, but leaving the worst sort of dementias to ravage our brains and torment our loved ones. Wait, we don’t just have to imagine that, do we? As Cave puts it, we are “not so much living longer as dying slower.” Will transhumanism inadvertently bring us more of this?

No one can say conclusively where the transhumanist movement will go, or whether it will ultimately change the conception of living and dying in the coming decades. One way or another, however, I think we could productively use a parallel movement to transhumanism: one that seeks to transcend our limited understanding and acceptance of death, and the fact that without the reality of life’s absence, we cannot understand life in the first place. We might call this movement “transmortalism.”

Of course, a huge amount of work to understand death has gone on over the millennia and starts with the straightforward observation that confronting the reality of death is the best way to strip it of its terror. An example is maranasati, the Buddhist practice of meditating on the prospect of one’s own corpse in various states of decomposition. “This body, too,” the monks recite, “such is its nature, such is its future, such its unavoidable fate.”

Frightening? Far from it. Such exposure provokes what psychologists call “desensitization,” in which repeated contact makes something previously frightening or foreign seem quite ordinary. Think of the fear of death like a simple phobia. If you are afraid of heights, the solution might be, little by little, to look over the edge. As the 16th-century French essayist Michel de Montaigne wrote of death, “Let us disarm him of his novelty and strangeness, let us converse and be familiar with him, and have nothing so frequent in our thoughts as death.”

Perhaps while we wait for the promises of transhumanism, we should hedge our bets with a bit of transmortalism, which has the side benefit of costing us no money. Who knows? Maybe the solution to the problem of death comes not by pushing it further away but, ironically, by bringing it much closer.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Coping With Complicated Grief

After loss, it’s a different path to ‘the new normal’ for those with depression

“Thank you for the intervention. Friends and family came to be with me. I agreed to be admitted to hospital. Am waiting for a bed. I had a horrible breakdown. I am sorry for worrying you.”

This was my message posted on Facebook to friends on October 19, 2014. It was over a year since my husband, Bob, passed away. Every day since he died on June 8, 2013 was like walking through thick, muddy water with a constant fog clouding my head.

I was a willing participant in the loss and grief cycle from day one. I had no interest in the future. The past was painful, the present bleak. Every day I woke up crying, for days, weeks, months, and soon a year passed. Depression is part of the initial journey. Many people feel like they can’t survive without their loved one. The agony is enormous, but the pain starts to diminish with time.

It is natural to experience intense grief after someone close dies, but complicated grief is different.

My story was different. The depression was pervasive and continued, even escalated. I journaled the experience, intermittently, in a blog. Posting my thoughts gave me temporary relief. Then I’d go down the rabbit hole again. What I didn’t realize was that I was experiencing something more than a normal grief journey. Though not diagnosed, researching my symptoms led me to what’s known as Complicated Grief.

The Intensity of Complicated Grief

According to The Center for Complicated Grief (CG) “[it] is a form of grief that takes hold of a person’s mind and won’t let go. It is natural to experience intense grief after someone close dies, but complicated grief is different. Troubling thoughts, dysfunctional behaviors or problems regulating emotions get a foothold and stall adaptation. Complicated grief is the condition that occurs when this happens.

“People with complicated grief don’t know what’s wrong. They assume that their lives have been irreparably damaged by their loss and cannot imagine how they can ever feel better. Grief dominates their thoughts and feelings with no respite in sight.”

According to the Mayo Clinic, CG can be determined “when the intensity of grief has not decreased in the months after your loved one’s death. Some mental health professionals diagnose CG when the grieving continues to be intense, persistent and debilitating beyond 12 months … Getting the correct diagnosis is essential for appropriate treatment, so a comprehensive medical and psychological exam is often done.”

The Diagnosis That Probably Saved My Life

I had seen several therapists. They tried to help, under the assumption that I was grieving as any woman would after the death of her husband. What I didn’t tell them was that my sadness had escalated to suicide ideation.

On the evening of Saturday October 18, 2014, I posted on Facebook: “Please take care of my cats.” My cry for help wasn’t a mystery to friends who were following my downward spiral. Phone calls went out from people in several cities to friends who lived near me who came to my house, then later family. Despite my uncharacteristic reaction screaming at everyone who entered the door and yelling at them to leave, I eventually calmed down and agreed to be taken to the hospital.

I was put in a room with no windows and a security guard. Some family members came in. The doctor followed and told me the medication I’d been taking for many years to control my clinical depression wasn’t working. When that happens, ironically, it can make you more depressed.

That diagnosis rocked me to the core and probably saved my life. Every day had been torture. And now I had someone who was telling me they could help me and life could actually get better.

I agreed to be admitted to hospital and new medication was prescribed by a hospital psychiatrist. I stayed there just over a week, eventually getting day passes, then a weekend pass. After my release, I was closely monitored to ensure my medication was doing what it should have done. I started seeking other ways to help me out of the dark pit and took part in several Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) programs, or what I refer to as retraining the brain to focus on the positive.

Live in the Moment

Today, I lead what those newly grieving are told is “the new normal life” because, when our loved ones die, life as we knew it is inevitably changed forever and will never go back to what we thought was our normal life. As Buddhist monk and peace activist, Nhat Hanh, said, “It is not impermanence that makes us suffer. What makes us suffer is wanting things to be permanent when they are not.”

The new life can be good if we come to terms with our losses; remember them with loving kindness; embrace our family, friends, and new people who come into our lives and accept that nothing is ever permanent in life. The biggest lesson I learned is to truly live in the moment and enjoy each precious day as a gift.

If you, or someone you know, has been suffering with extreme grief symptoms for over a year it might be time to seek help.

Coping with Grief and Loss

While grieving a loss is an inevitable part of life, there are ways to help cope with the pain, come to terms with your grief and eventually, find a way to pick up the pieces and move on with your life. Here are some suggestions from Help Guide:

1. Acknowledge your pain.

2. Accept that grief can trigger many different and unexpected emotions.

3. Understand that your grieving process will be unique to you.

4. Seek out face-to-face support from people who care about you.

5. Support yourself emotionally by taking care of yourself physically.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Depression symptoms increase over last year of life

By Lisa Rapaport

Many people experience worsening depression symptoms over their final year of life, and a U.S. study suggests that women, younger adults and poor people may be especially vulnerable.

For the study, researchers examined data on 3,274 adults who participated in the nationwide Health and Retirement Study and died within one year of the assessment. All of the participants had completed mental health questionnaires and provided information on any medical issues they had as well as demographic factors like income and education levels.

Rates of depressive symptoms increased over the last year of life, particularly within the final months, the study found. By the last month of life, 59% of the participants had enough symptoms to screen positive for a diagnosis of depression, although they were not formally evaluated and diagnosed by clinicians.

“Patients with depression have worse survival outcomes than non-depressed patients, making depression a critical issue to screen for and manage in the context of serious illness,” Elissa Kozlov of the Rutgers University Institute for Health, Health Policy, and Aging Research in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and colleagues write in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.

And, “psychological symptoms, such as depression, have a negative impact on patients’ quality of life as they near the end of life,” Kozlov and colleagues write.

Researchers had asked participants whether they experienced eight things over the previous week: depression, sadness, restless sleep, unhappiness, feeling like everything takes effort, lack of motivation and loneliness. People with at least three symptoms might screen positive for depression, the study team writes.

Across the entire Health and Retirement Study population, including people who didn’t die within a year of their most recent assessments, about 23% of participants have at least three of these symptoms, the researchers also note.

In the current analysis, depression scores remained relatively stable from 12 to four months prior to death, then steadily increased. With four months to live, 42% of participants had at least three symptoms of depression, and with one month remaining, 59% did.

One year before death, women had higher depression symptom scores, with almost three symptoms on average compared to about two for men. With one month to live, both men and women had three or more symptoms and there was no longer a meaningful difference between the sexes.

Differences in depression scores based on age and income were also more pronounced one year before death, and became less pronounced closer to death, the study found.

However, the youngest and poorest participants had the highest depression scores at all points in time.

As death approached, nonwhite participants also had increasingly high depression scores.

And, one month before death, people without a high school education had the highest depression scores of all, averaging almost five symptoms.

The study wasn’t designed to prove whether or how terminal illness might impact mental health, or the reverse.

Even so, the results underscore the importance of screening for mental health problems and treating conditions like depression in the final months of life, the researchers conclude.

“Given the range of options to treat depression, unaddressed depressive symptoms in the last year of life must be a focus of both quality measurement and improvement,” the study authors write. “While depressive symptoms at the end of life are common, they are treatable and must be proactively addressed to reduce distress and ensure that everyone has the opportunity to experience a ‘good death,’ free of depressive symptoms.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The Ethical Will

Life Is About More Than Your Possessions

Have you considered how to pass on your non-material assets?

When people find out Debby Mycroft helps people write ethical wills, she always gets a predictable response: The Lament.

“They say, ‘Oh, I wish I had a letter from my dad or grandmother or great aunt,’ whoever that person was. I have not come across a single person who has not wanted a letter from that special person,” says Mycroft, founder of Memories Worth Telling.

Unlike legal wills, ethical wills — also known as legacy letters — are not written by lawyers, but by you. They can include life lessons, values, blessings and hopes for the future, apologies to those you fear you may have hurt or gratitude to those you think you have not thanked enough. Traditionally, they were letters written by parents to children, to be read after death.

People who do not have children address them to friends or groups. One of Mycroft’s clients was placed in child protective services when she was quite young because her parents were addicts. “She had a rough upbringing. She intentionally decided not to have children herself. But she wanted to write an ethical will to other foster kids to let them know [they] can survive this,” Mycroft explains.

Why Write an Ethical Will?

Think that your life isn’t important enough to warrant an ethical will? Mycroft disagrees, saying, “You don’t have to be a war hero or a Nobel Peace Prize winner for your story to have value. When people accept awards at the Olympics, they thank the people who had an impact on their life, like Mom or Dad, who was always there to take them to training.”

But there’s an even more important reason you might want to consider a legacy letter. According to Barry K. Baines, author of Ethical Wills: Putting Your Values on Paper, such documents can bring enormous peace of mind.

Baines recalls one dying patient who was bereft because he felt there would be no trace of him when he left. “The first wave would wash away his footprints. That sense of hopelessness and loss was overwhelming,” says Baines. The man rated his suffering at 10 out of 10; after he wrote his ethical will, his suffering reduced to zero.

Don’t wait until you are on your deathbed to do this, Baines warns. As soon as you articulate your values, suddenly you start to live your life more intentionally. Especially if you share it.

“Live your life as you wish to be remembered,” Baines advises. Plus, he adds, legacy letters can help with making amends, addressing regrets and healing relationships.

Ethical Will: Telling Your Own Story

If you don’t feel capable of writing your legacy letter yourself, you can use an online template, take a workshop, read a book about it or work with a professional writer.

But don’t judge your skills harshly. Baines finds that whether people are educated or not or if their letters are simple or complex, they always have a certain elegance because of the truth they contain. “When the families get one, they just glow,” Baines says, adding, “This is a unique gift that only you can give.”

When you write your letter, don’t just say, “My core values are consideration, gratitude, kindness, simplicity,” advises Mycroft. Tell a story about how you’ve lived these values.

In her own legacy letter, Mycroft told her kids about a temp job she had as a teen. She appeared nicely dressed in a skirt, blouse and heels. When she walked in, the employers gave her a funny look and asked, “Why do you think you are here?”

She explained the agency had sent her out for secretarial work. Then her employers handed her a hard hat and steel-toed shoes. “That’s when I look at them quizzically.”

Turns out they were a plastic-bag manufacturer and she was supposed to sort through damaged goods to salvage the ones that could be sold.

“I was so angry that that agency had sent me out on that job. It was hot and humid in Virginia. I was fuming,” Mycroft says. “When I got home, my parents started grilling me. They said, ‘Did you agree on this job?’” And Mycroft confirmed that she did.

They asked what the contract said. Mycroft replied that the contract was pretty clear. Did she sign the contract, her parents wanted to know?

“Yes, but,” she says she told them. “And my parents said, ‘You signed it; you’re committed to it.’”

Mycroft stuck with the job as promised. “That was my first lesson in integrity, perseverance and diligence,” she recalls. She did what she said she would do. As a postscript, she got fantastic jobs from the agency over the rest of the summer. They knew they could count on her.

What Goes Into the Legacy Letter and What Stays Out

Ethical wills are often likened to letters from the heart, so perhaps the best advice is to literally write a love letter.

Love letters don’t recriminate. They don’t judge. They don’t scold. A love letter is there to show how much someone matters to you.

Criticisms and judgments should be left out, advises Mycroft. It’s okay to include regrets and family secrets, even if they hurt. If worded properly, these could bring the family to a place of acceptance and understanding.

She notes, “Sometimes when those things are hidden for so long it causes a lot of resentment — as in] why didn’t they tell me I was adopted? I wish I had known.”

“Definitely avoid manipulation,” Mycroft advises. “Legacy letters are beautiful expressions of love and encouragement, telling other people what is so fantastic about them. I do not think they should be hands reaching up from the grave slapping you or saying, ‘I told you so.’”

Think about how your letter might be received. Baines worked with a woman who had a very hard life. “Every part of her ethical will was blame and guilt-tripping,” he recalls. While some people can turn around a bad experience and use it is an example of what not to do, this woman could not.

“It almost seemed like she was purposely trying to hurt people,” Baines says. But eventually she realized that and gave up, sparing her family the hurt she would cause them.

Get a Second Opinion

Baines believes writers should show their legacy letter to a trusted friend before passing it on, to avoid inadvertent errors. Your reader might say, “You mentioned your two children, but you only write about one and not the other.” That could be extremely hurtful.

Baines also urges people to share the letters while they’re living. It might be painful, but there’s still potentially an opportunity to mend wounds. After you die, there’s no recourse at all.

What About Videos or Selfie Videos?

Some people make videos or selfies of their ethical wills, but keep in mind that technologies can become outmoded.

Mycroft gave both her children the letter and a video of her reading the letter so they not only have her words, but can also hear her voice.

“I’ve heard of people saving voicemails of people who have passed on,” she says. “Can you imagine saving a voicemail and all it says is ‘Susie, are you there? Can you pick up? Hello?’ If you’re willing to save that message just to hear their voice, how much more powerful would it be to hear your voice reading that letter?”

The Time Is Now

The time to write your spiritual legacy is now. Mycroft provides a case in point about her mother, who knew the family lore and lineage.

“I gave her one of these fill-in-the-blank family history books because I wanted to make sure it was preserved,” says Mycroft. “Five years later, when she had passed away and I went to clean out her office, I found the book. It was completely empty.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

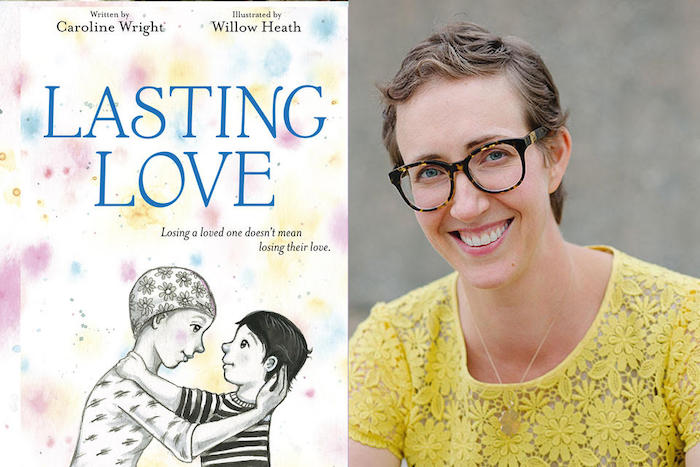

This Seattle writer wants to change how we talk to kids about death

Facing her own terminal diagnosis, a cookbook author pivots to recipes for coping with grief.

by Tom Keogh

Seattle-based cookbook author Caroline Wright can teach you how to make a salad for four with grilled escarole, peaches, prosciutto, mozzarella and basil oil.

She can show you how a sandwich of grilled manchego cheese and sausage on peasant bread is made in the style of a master chef from Catalonia. For dessert, she’ll tempt you with a wicked coconut-caramel cake with malted chocolate frosting.

But when the leftovers are wrapped and put away, Wright can also impart some hard-won wisdom: how to talk to kids about death.

Wright, who studied cuisine at a renowned cooking school in Burgundy, France, always wanted to write as much as develop her skills in a well-appointed kitchen. At age 23, she became a food editor at Martha Stewart Living, and later brought her crisp, engaging voice to her cookbooks, Twenty-Dollar, Twenty-Minute Meals, Cake Magic! and Catalan Food: Culture and Flavors from the Mediterranean (co-authored with Daniel Olivella).

She hasn’t stopped writing about food. But in 2017 she was diagnosed with a glioblastoma, an aggressive, rapidly growing brain tumor, similar to the one that killed Sen. John McCain. With the possibility of death looming large, Wright turned her prose toward facing her own mortality — and starting the conversation with her kids.

Luminous and voluble in person, Wright is a self-described, inveterate doer. When not writing or cooking, she’s pursuing photography or quilting or knitting. She can’t stop making things happen, whether it’s tinkering with recipes for her next cookbook, or organizing a panel discussion at Town Hall (Saturday, Nov. 9) on children and grief. The event will explore how we talk to kids about death, a topic with no simple bearings.

Wright has written two recent books on the theme of child bereavement, inspired by her and her husband Garth’s agonizing challenge of communicating with their young sons about Wright’s still-uncertain prognosis.

The Caring Bridge Project (which came out in February) is a collection of Wright’s online journal entries from her year of chemotherapy and radiation treatment. It’s part of Wright’s written legacy to her boys, Henry, 7, and Theodore, 4. But she intended it, too, for a broader readership: families facing similar experiences with children’s anxiety and despair over loss.

This past summer she published Lasting Love, a picture book for reading aloud to bereaved kids. The heartbreaking but emotionally affirming story, with comforting illustrations by Willow Heath, is about a dying mother returning home from the hospital with a formidable friend: a mighty, furry creature who will always remain by her child’s side, as both an avatar of her powerful love, and as a faithful companion who never judges grief in any form.

Halfway through the tale, the mother passes.

“The child would know,” says Wright of her decision to include the mother’s death. “So stepping around that seemed silly. I wanted the kid to be part of spreading her ashes.”

For Wright, there was no option but honesty. She knew her kids would watch her change, physically, during treatment, and they would find her less available. Keeping them in the dark — especially the older boy, Henry — would have been unfair. “The thing kids can’t rebound from is broken trust,” she says. “There’s no resolution for that.”

When she and Garth first talked with Henry about her cancer, and how she and her doctors were doing everything they could, but she might die anyway, there were tears. But Henry devised a helpful analogy:

“Mommy’s brain is a garden, and there’s a weed in it.”

“Henry and I have had amazing conversations, poetic and hard,” Wright says. “If I die, I want both boys to have a relationship with their memories of me. If I lied to them, it would sully that relationship.”

Thirty-two months after Wright was told she’d likely have 12 to 18 months to live, she is miraculously cancer-free, but vulnerable to a swift reemergence of the glioblastoma. If you take cancer out of the picture, she actually became healthier while fighting the disease, radically changing her diet, dropping 40 pounds and growing lean and strong through yoga, energy work and exercise.

Wright says the boys now occasionally bring up her cancer at random times. When Theodore recently saw her short hair wet and matted after a shower, he grew weepy, recalling her treatment-related baldness, and associating it with being away from him.

The profundity of loss, and the despondency of a child left without the constancy of a loved one’s care, makes Lasting Love a benevolent bridge between a parent and son or daughter going through these troubles.

“The theme of Lasting Love is, literally, love lasting forever,” Wright says. “That’s what we were telling Henry. That was the only piece of hope that we could give him: Mommy’s fighting very hard. And even if mommy dies, the connection you have with her is never going to go away. And there are many loving people surrounding you.”

Wright’s Town Hall event is part of her outreach mission to regional families and to nonprofits concerned with children and bereavement. Among them is Safe Crossings, which supports grieving kids of all ages, at little or no cost. Amy Thompson, program coordinator, will join the panel, along with therapists from other organizations.

Thompson says the field of grief counseling for early childhood through adolescence is growing because of a rise in traumatic losses: gun-related murders, opioid-overdose deaths and suicides. Grieving kids are often isolated, subject to bullying, and told to “get over it” by clueless adults.

“The message from society to grieving young people is ‘move on,’ ” Thompson says. “But if you’re intensely grieving for months or even years after a death, there’s nothing wrong with you. Loss changes over time. As children grow and reach new developmental milestones, they can better process the permanency of death, and we see them regrieve.”

The attention Wright and Lasting Love are receiving in therapy circles and in the media is helping to normalize grief in children — in everyone, really. When she learned she had beaten seemingly impossible odds and, while not out of the woods, is without cancer, Wright celebrated with her family by making a favorite cake, although with a few adjustments: it was sugar-free, gluten-free and covered in carob frosting instead of her once-beloved chocolate.

“I live with great respect for this thing that may happen to me again,” Wright says of the glioblastoma cells that might still be lurking in her brain. “But I don’t live in fear of it. There is nothing to be gained by that. I might die and I might not.”

But the bond between parent and child will last beyond death, she says. “Kids are resilient. With support, they will have full lives.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Grounding Ourselves

On rethinking our views of green space and funeral options as we plan for the final disposition of our bodies.

By Regina Sandler-Phillips

In 2008, Vietnamese Zen master and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh wrote “The Bells of Mindfulness” about the need for collective awakening to protect the earth. One decade later, master composter David Buckel connected the self-immolation of Buddhist monastics to his own self-immolation for action against climate change. Tragically, Buckel’s self-described “early death by fossil fuel” caught public attention in a way that his long-term, nationwide contributions to community composting could not. Our most sustainable practices — those that quietly prevent the depletion of vital natural resources — are rarely headline-grabbing.

Natural burial, like community composting, involves acceptance that the organic remains of the living are neither trash nor personal commodities. They belong to the earth. Yet, even though human bodies have been continuously returned to the earth for millennia, the idea that our world will be overrun by cemeteries remains entrenched in popular consciousness.

The experience of the United Kingdom — a tiny island nation that has long promoted cremation to save space — teaches otherwise. “For most environmentalists, it’s actually better to fade away than burn out,” concluded UK ethics journalist Leo Hickman back in 2005. “Our lives … already result in enough gratuitous combusting of fossil fuels. Much better, in death, to compost down as nature intended.” (Read more about the energy inputs, emissions, and toxic impacts of cremation in part one of this series.)

While it may seem alien to conventional expectations, the reuse of graves is a sustainable, long-established practice in Europe and elsewhere. In the historic City of London Cemetery, 1,500 out of 780,000 graves have been reused to date — a practice legalized for the municipality in 2007. As reported in The Guardian, graves chosen for reuse must be at least 75 years old, and notices must be posted for six months at the grave and in advertisements. If anyone connected with the grave raises an objection, the grave will not be reused. Gary Burks, who first came to live at the cemetery as the young child of a gardener and is now its superintendent, reports that very few objections have been registered.

In most cases, the original decomposed remains are lowered by deepening the grave, allowing for a new burial above. The original headstone inscription is preserved, but reversed to allow for a new inscription on the other side of the headstone. Burks believes that, with continued sensitive application of these procedures, the beautifully landscaped grounds will be able to accommodate interments indefinitely.

Most predictions of disappearing space focus on cemeteries within major urban centers. But just as city dwellers regularly leave these centers in search of more spacious real estate, the majority of burial plots — especially in the US — remain available outside of city limits. Like Hickman in the UK, American environmental planning professor Christopher Coutts has concluded that the most sustainable form of body disposition is burial without embalming in a simple biodegradable covering, followed by reuse of graves after bodies have decomposed back to the earth.

Another common variation of grave reuse involves a deeper excavation of graves at the outset, so that two or three family members can be buried one on top of the other(s) in the same plot. “Multiple-depth” burial practices are recognized in the United States, and ritually acceptable in Christianity, Judaism, and Islam.

While the utilitarian, lawn-style suburban cemeteries of the mid-twentieth century may not represent today’s ideal landscaping aesthetics, they still preserve basic green space against a range of more fossil-fuel-intensive onslaughts. The Green Burial Council recognizes this with three levels of North American cemetery standards.

“Hybrid” burial grounds are cemeteries or cemetery sections that simply forego the use of concrete vaults or other outer containers to reinforce the ground. Such vaults are never required by state law in the US, but rather by the regulations of individual cemeteries. Except in areas where the earth is particularly shifting and unstable (as in cities built below sea level), most Jewish and Muslim burial grounds would qualify as “hybrid” — since these traditions have long upheld a simple, natural return to the earth.

“Natural” burial grounds, besides foregoing vaults and outer containers, do not allow for burial of any bodies embalmed with toxic chemicals, or of any containers not made of biodegradable materials. Again, this is consistent with traditional Jewish and Muslim practices.

“Conservation” burial grounds are natural burial grounds legally committed to long-term stewardship for land conservation and preservation of natural habitat. There are very few designated conservation burial grounds at this time — and significantly fewer people can be buried in conservation burial grounds than in conventional cemeteries, which are zoned for many more graves.

Beyond the technicalities of “green” certification, there are always sustainability tradeoffs between each organic, inorganic, emotional, social, and economic consideration in the human ecosystem of funeral arrangements. For example, the greenhouse gas emissions of long-distance transport to a certified natural burial ground must be weighed against the availability of graves in more local cemeteries that support natural burial practices.

As the Funeral Consumers Alliance points out, “You can make any burial greener by eliminating embalming, and using a shroud or a biodegradable casket. Omit the vault if the cemetery will allow it. Otherwise, ask to use a concrete grave box with an open bottom, have holes drilled in the bottom of the vault, or invert the vault without its cover, so the body can return to the earth.”

Of course, the least privileged are not afforded this full range of choices. A cemetery of layered graves for the indigent and unclaimed is known as a potter’s field, referring back to the New Testament. Potters Fields Park in London is quite cheerful about its origins. In New York City, several now-upscale parks served as potter’s fields long before Hart Island — the largest mass burial ground in the United States — was opened for that purpose. More than one million dead, most of them lost to family and forgotten by history, have been buried on Hart Island in layered trenches by prison inmates since 1869.

Following decades-long efforts of family and community activists, supported by organizations like the Hart Island Project and the New York Civil Liberties Union, relatives of those buried on the island have won limited visitation rights in recent years. Those who “affirm a close personal relationship” can visit their corresponding burial area up to twice a month, while access for the general public remains restricted to a public viewing gazebo once a month. This past spring, the New York City Council moved formally toward transferring the jurisdiction of this municipal cemetery from the Department of Corrections to the Parks Department.

A few years earlier, the New York State legislature outlawed the use — without consent — of presumably unclaimed bodies for medical research or funeral embalmer training prior to Hart Island burial. Meanwhile, Hart Island continues to challenge us with a tangled thicket of ethical dilemmas, from cadaver shortages through prison reform to land use deliberations.

We may offer tips for “how to avoid the fate of a common grave,” but the unspoken truth is that we are all fated to return to a common earth. The most integrated solutions to the dilemmas of Hart Island actually point toward the most equitable and sustainable consumer choices for all of us at death: layered burials in simple, biodegradable containers; preservation of urban green spaces and history; public transportation access; and community education and counseling for informed funeral decision-making — including fully consensual arrangements for needed anatomical gifts.

Archaeological discoveries remind us that layered civilizations inevitably result in layered burials. Our first priority should be helping to insure that our own civilization will not be prematurely buried (or drowned) in the upheavals of climate change — and that there will be equal access, regardless of income, to whatever sustainable burial options exist locally.

In a poignant twist, one of the family members most active in the struggle to open Hart Island as a public space made arrangements for her own burial there. Rosalee Grable, whose mother was buried on the island in 2014, died two years later at the age of 65. “I am getting quite eager for my little spot on Hart Island,” Grable reflected shortly before her death. She knew that under then-current city regulations she would need to forego a funeral attended by family and friends, that her burial would not be confirmed until 30 days afterward, and that local friends would have difficulty visiting unaccompanied by her long-distance family members.

Even so, Rosalee Grable leveraged her power of choice in solidarity with so many whose lack of choice brought them to the same place. By deliberately choosing “the fate of a common grave,” she left a legacy that challenges all of us to plan the final dispositions of our own bodies in affirmation of our common humanity — and our common earth.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!