A simple conversation could have changed so much…

By Melissa Reader

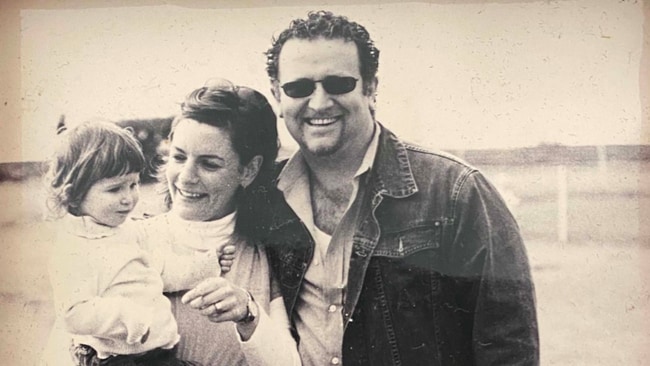

After losing her husband Mauro tragically young, Melissa Reader is personally motivated to help more Australians talk about the end stages of life. Because accepting that death is a part of life is the first step to ensuring the final stages of living are done with dignity, and surrounded by love.

It wasn’t long ago that these topics were shrouded in stigma. And while we have some way to go in making these areas of life safe topics of discussion for everyone, there’s no doubt that over the last 10 years we’ve come a long way.

So it’s still surprising that we have allowed death to remain a taboo subject. Death is as universal as life – we all die. And just like mental health, sex and identity, talking about it openly normalises the experience and helps to make it the best it can be, for everyone involved.

Avoiding the topic

It’s a known fact that ‘what we resist, persists’, so our fears around death and dying heighten and become more difficult to address as time goes on.

The lack of communication at the end of life leads to a lack of preparation; right now in Australia, only 14% of us have a plan in place for how we want to die. The last stage of life and the end of life is never going to be easy – but it can be better, and learning to talk, plan and care for each other when the time comes is key. Or we end up with a big gap between what we hope for, and what happens, which is what happened in our family.

If we had managed to have the important conversations, like how to make the most of the time ahead, we might have made different decisions.

How my family changed forever

We were a very normal, happy, busy family, with three children. Our youngest child, Orlando, was just nine months old when my husband Mauro’s diagnosis came completely out of the blue.

He was 40-years-old. Through the 15 months of his illness, we did our best to navigate life, family needs and the confronting and ever-changing demands of his cancer disease. But we avoided having honest and open end-of-life conversations as a couple, as a family, and with his medical team. We didn’t understand, or maybe we couldn’t accept, that he was terminally ill – that he was dying.

The regret never fades

I still feel so sad about the way Mauro spent the last stage of his life – in and out of the hospital, away from his family, and his home. We didn’t think about how to really make the most of those precious months together. We never accessed palliative care, which would have been so helpful, and we weren’t in any way prepared for his death.

It all flew by in a painful blur and suddenly, I was standing beside him in the ICU, reeling, and finally realising that he was about to die. Realising that we’d missed so many moments for love, connection, memory, and legacy. Realising that Mauro was going to die in a cold, clinical and unfamiliar setting – something he wouldn’t have wanted.

We were left without a husband, and a father, and I was holding many deep regrets about the way the last stage of his life played out.

How to talk about death, better

Honesty and kindness are not mutually exclusive. By having more open and candid conversations, and planning together where everyone is involved is the key to making the experience the best it can be.

Unfortunately, life doesn’t offer us a chance to re-do this scenario. My advice is this: be gentle, be brave, and try to open more conversations with family and friends about what’s most important in the last stage of our lives.

Remember, it’s your compassion, not your vocabulary that matters – there are no perfect words. Rather than getting caught up in trying to find the right things to say, my advice is to instead focus on timing and tone. If you get these things right, the words tend to find their own way. Take your time, use gentle and well-spaced questions and be prepared to revisit conversations over a few sittings.

And if you need support with where to start or how to unravel what comes of these chats, you can always reach out to the Violet Initiative. We’re a national not-for-profit that’s helped thousands of Australian families navigate this life stage.

A personal pledge

I made it my life’s calling to create a safe space where family, friends and colleagues of someone who is in the last stage of life can go for support, so they know that they aren’t alone and that help is available.

So next time you’re catching up with friends and you find yourself discussing your mental health, take a moment to think of some of the end-of-life conversations that might lie ahead, and make a pact to approach these with the same openness and honesty.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!