Insights into the little-studied realm of last words.

By Michael Erard

Mort Felix liked to say that his name, when read as two Latin words, meant “happy death.” When he was sick with the flu, he used to jokingly remind his wife, Susan, that he wanted Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” played at his deathbed. But when his life’s end arrived at the age of 77, he lay in his study in his Berkeley, California, home, his body besieged by cancer and his consciousness cradled in morphine, uninterested in music and refusing food as he dwindled away over three weeks in 2012. “Enough,” he told Susan. “Thank you, and I love you, and enough.” When she came downstairs the next morning, she found Felix dead.

During those three weeks, Felix had talked. He was a clinical psychologist who had also spent a lifetime writing poetry, and though his end-of-life speech often didn’t make sense, it seemed to draw from his attention to language. “There’s so much so in sorrow,” he said at one point. “Let me down from here,” he said at another. “I’ve lost my modality.” To the surprise of his family members, the lifelong atheist also began hallucinating angels and complaining about the crowded room—even though no one was there.

Felix’s 53-year-old daughter, Lisa Smartt, kept track of his utterances, writing them down as she sat at his bedside in those final days. Smartt majored in linguistics at UC Berkeley in the 1980s and built a career teaching adults to read and write. Transcribing Felix’s ramblings was a sort of coping mechanism for her, she says. Something of a poet herself (as a child, she sold poems, three for a penny, like other children sold lemonade), she appreciated his unmoored syntax and surreal imagery. Smartt also wondered whether her notes had any scientific value, and eventually she wrote a book, Words on the Threshold, published in early 2017, about the linguistic patterns in 2,000 utterances from 181 dying people, including her father.

Despite the limitations of this book, it’s unique—it’s the only published work I could find when I tried to satisfy my curiosity about how people really talk when they die. I knew about collections of “last words,” eloquent and enunciated, but these can’t literally show the linguistic abilities of the dying. It turns out that vanishingly few have ever examined these actual linguistic patterns, and to find any sort of rigor, one has to go back to 1921, to the work of the American anthropologist Arthur MacDonald.

To assess people’s “mental condition just before death,” MacDonald mined last-word anthologies, the only linguistic corpus then available, dividing people into 10 occupational categories (statesmen, philosophers, poets, etc.) and coding their last words as sarcastic, jocose, contented, and so forth. MacDonald found that military men had the “relatively highest number of requests, directions, or admonitions,” while philosophers (who included mathematicians and educators) had the most “questions, answers, and exclamations.” The religious and royalty used the most words to express contentment or discontentment, while the artists and scientists used the fewest.

MacDonald’s work “seems to be the only attempt to evaluate last words by quantifying them, and the results are curious,” wrote the German scholar Karl Guthke in his book Last Words, on Western culture’s long fascination with them. Mainly, MacDonald’s work shows that we need better data about verbal and nonverbal abilities at the end of life. One point that Guthke makes repeatedly is that last words, as anthologized in multiple languages since the 17th century, are artifacts of an era’s concerns and fascinations about death, not “historical facts of documentary status.” They can tell us little about a dying person’s actual ability to communicate.

Some contemporary approaches move beyond the oratorical monologues of yore and focus on emotions and relationships. Books such as Final Gifts, published in 1992 by the hospice nurses Maggie Callanan and Patricia Kelley, and Final Conversations, published in 2007 by Maureen Keeley, a Texas State University communications-studies scholar, and Julie Yingling, professor emerita at Humboldt State University, aim to sharpen the skills of the living for having important, meaningful conversations with the dying. Previous centuries’ focus on last words has ceded space to the contemporary focus on last conversations and even nonverbal interactions. “As the person gets weaker and sleepier, communication with others often becomes more subtle,” Callanan and Kelley write. “Even when people are too weak to speak, or have lost consciousness, they can hear; hearing is the last sense to fade.”

I spoke to Maureen Keeley shortly after the death of George H. W. Bush, whose last words (“I love you, too,” he reportedly told his son, George W. Bush) were widely reported in the media, but she said they should properly be seen in the context of a conversation (“I love you,” the son had said first) as well as all the prior conversations with family members leading up to that point.

At the end of life, Keeley says, the majority of interactions will be nonverbal as the body shuts down and the person lacks the physical strength, and often even the lung capacity, for long utterances. “People will whisper, and they’ll be brief, single words—that’s all they have energy for,” Keeley said. Medications limit communication. So does dry mouth and lack of dentures. She also noted that family members often take advantage of a patient’s comatose state to speak their piece, when the dying person cannot interrupt or object.

Many people die in such silence, particularly if they have advanced dementia or Alzheimer’s that robbed them of language years earlier. For those who do speak, it seems their vernacular is often banal. From a doctor I heard that people often say, “Oh fuck, oh fuck.” Often it’s the names of wives, husbands, children. “A nurse from the hospice told me that the last words of dying men often resembled each other,” wrote Hajo Schumacher in a September essay in Der Spiegel. “Almost everyone is calling for ‘Mommy’ or ‘Mama’ with the last breath.”

It’s still the interactions that fascinate me, partly because their subtle interpersonal textures are lost when they’re written down. A linguist friend of mine, sitting with his dying grandmother, spoke her name. Her eyes opened, she looked at him, and died. What that plain description omits is how he paused when he described the sequence to me, and how his eyes quivered.

But there are no descriptions of the basics of last words or last interactions in the scientific literature. The most linguistic detail exists about delirium, which involves a loss of consciousness, the inability to find words, restlessness, and a withdrawal from social interaction. Delirium strikes people of all ages after surgery and is also common at the end of life, a frequent sign of dehydration and over-sedation. Delirium is so frequent then, wrote the New Zealand psychiatrist Sandy McLeod, that “it may even be regarded as exceptional for patients to remain mentally clear throughout the final stages of malignant illness.” About half of people who recover from postoperative delirium recall the disorienting, fearful experience. In a Swedish study, one patient recalled that “I certainly was somewhat tired after the operation and everything … and I did not know where I was. I thought it became like misty, in some way … the outlines were sort of fuzzy.” How many people are in a similar state as they approach death? We can only guess.

We have a rich picture of the beginnings of language, thanks to decades of scientific research with children, infants, and even babies in the womb. But if you wanted to know how language ends in the dying, there’s next to nothing to look up, only firsthand knowledge gained painfully.

After her father died, Lisa Smartt was left with endless questions about what she had heard him say, and she approached graduate schools, proposing to study last words academically. After being rebuffed, she began interviewing family members and medical staff on her own. That led her to collaborate with Raymond Moody Jr., the Virginia-born psychiatrist best known for his work on “near-death experiences” in a 1975 best-selling book, Life After Life. He has long been interested in what he calls “peri-mortal nonsense” and helped Smartt with the work that became Words on the Threshold, based on her father’s utterances as well as ones she’d collected via a website she called the Final Words Project.

One common pattern she noted was that when her father, Felix, used pronouns such as it and this, they didn’t clearly refer to anything. One time he said, “I want to pull these down to earth somehow … I really don’t know … no more earth binding.” What did these refer to? His sense of his body in space seemed to be shifting. “I got to go down there. I have to go down,” he said, even though there was nothing below him.

He also repeated words and phrases, often ones that made no sense. “The green dimension! The green dimension!” (Repetition is common in the speech of people with dementia and also those who are delirious.) Smartt found that repetitions often expressed themes such as gratitude and resistance to death. But there were also unexpected motifs, such as circles, numbers, and motion. “I’ve got to get off, get off! Off of this life,” Felix had said.

Smartt says she’s been most surprised by narratives in people’s speech that seem to unfold, piecemeal, over days. Early on, one man talked about a train stuck at a station, then days later referred to the repaired train, and then weeks later to how the train was moving northward.

“If you just walk through the room and you heard your loved one talk about ‘Oh, there’s a boxing champion standing by my bed,’ that just sounds like some kind of hallucination,” Smartt says. “But if you see over time that that person has been talking about the boxing champion and having him wearing that, or doing this, you think, Wow, there’s this narrative going on.” She imagines that tracking these story lines could be clinically useful, particularly as the stories moved toward resolution, which might reflect a person’s sense of the impending end.

In Final Gifts, the hospice nurses Callanan and Kelley note that “the dying often use the metaphor of travel to alert those around them that it is time for them to die.” They quote a 17-year-old, dying of cancer, distraught because she can’t find the map. “If I could find the map, I could go home! Where’s the map? I want to go home!” Smartt noted such journey metaphors as well, though she writes that dying people seem to get more metaphorical in general. (However, people with dementia and Alzheimer’s have difficulty understanding figurative language, and anthropologists who study dying in other cultures told me that journey metaphors aren’t prevalent everywhere.)

Even basic descriptions of language at the end of life would not only advance linguistic understanding but also provide a host of benefits to those who work with the dying, and to the dying themselves. Experts told me that a more detailed road map of changes could help counter people’s fear of death and provide them with some sense of control. It could also offer insight into how to communicate better with the dying. Differences in cultural metaphors could be included in training for hospice nurses who may not share the same cultural frame as their patients.

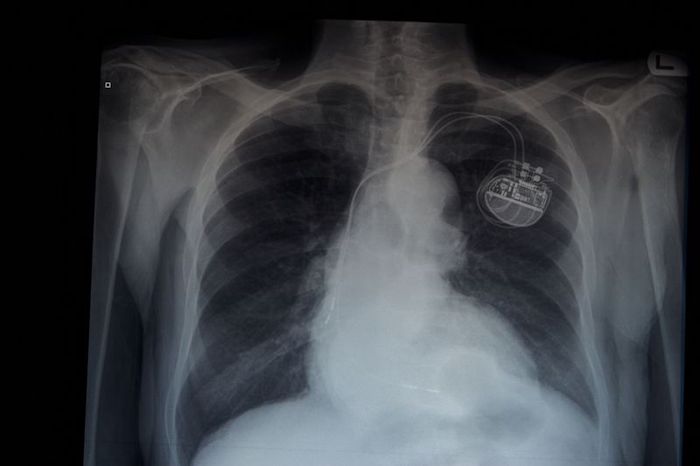

End-of-life communication will only become more relevant as life lengthens and deaths happen more frequently in institutions. Most people in developed countries won’t die as quickly and abruptly as their ancestors did. Thanks to medical advances and preventive care, a majority of people will likely die from either some sort of cancer, some sort of organ disease (foremost being cardiovascular disease), or simply advanced age. Those deaths will often be long and slow, and will likely take place in hospitals, hospices, or nursing homes overseen by teams of medical experts. And people can participate in decisions about their care only while they are able to communicate. More knowledge about how language ends and how the dying communicate would give patients more agency for a longer period of time.

But studying language and interaction at the end of life remains a challenge, because of cultural taboos about death and ethical concerns about having scientists at a dying person’s bedside. Experts also pointed out to me that each death is unique, which presents a variability that science has difficulty grappling with.

And in the health-care realm, the priorities are defined by doctors. “I think that work that is more squarely focused on describing communication patterns and behaviors is much harder to get funded because agencies like NCI prioritize research that directly reduces suffering from cancer, such as interventions to improve palliative-care communication,” says Wen-ying Sylvia Chou, a program director in the Behavioral Research Program at the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health, who oversees funding on patient-doctor communication at the end of life.

Despite the faults of Smartt’s book (it doesn’t control for things such as medication, for one thing, and it’s colored by an interest in the afterlife), it takes a big step toward building a corpus of data and looking for patterns. This is the same first step that child-language studies took in its early days. That field didn’t take off until natural historians of the 19th century, most notably Charles Darwin, began writing down things their children said and did. (In 1877, Darwin published a biographical sketch about his son, William, noting his first word: mum.) Such “diary studies,” as they were called, eventually led to a more systematic approach, and early child-language research has itself moved away from solely studying first words.

“Famous last words” are the cornerstone of a romantic vision of death—one that falsely promises a final burst of lucidity and meaning before a person passes. “The process of dying is still very profound, but it’s a very different kind of profoundness,” says Bob Parker, the chief compliance officer of the home health agency Intrepid USA. “Last words—it doesn’t happen like the movies. That’s not how patients die.” We are beginning to understand that final interactions, if they happen at all, will look and sound very different.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!