The LifeCourse program educates patients on how to write a medical directive, how to care for themselves, and even how to make the best of their remaining time — and has achieved striking results in the way people use medical care in their final months.

By Glenn Howatt

Bob DeMarce made a living as a funeral director, but he didn’t think much about his own mortality until he developed cancer. He soon learned it took more than being sick to prepare him for death.

DeMarce became one of hundreds of Minnesotans enrolled in a research program that prepares patients and families for the end of life. Conducted by Allina Health, the LifeCourse program educates patients on how to write a medical directive, how to care for themselves, and even how to make the best of their remaining time — and has achieved striking results in the way people use medical care in their final months.

DeMarce already had plenty of doctors, care coordinators and rehab specialists to attend to his medical needs. LifeCourse gave him a “care guide” — a nonmedical counselor — who met with him and his family to help them set goals and provide support.

“Most people would hesitate to talk about this sort of thing,” said the 75-year-old DeMarce, who has had two bouts of lung cancer in addition to colon cancer. “With the different scares I had with cancer … We did want to get things straightened out.”

One goal of the program is to increase the number of patients with advance care directives, which research has shown can reduce the amount of unnecessary and often unwanted care at the end of life.

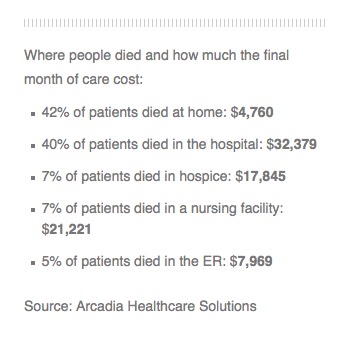

And the results were dramatic: Patients in the LifeCourse intervention group had fewer hospital inpatient days, fewer emergency room visits and less intensive care, compared with a control group that was tracked but did not work with care guides. About 85 percent completed a living will, compared with 30 percent in the control group.

But the program also aims to improve the quality of life at a time when chronically ill patients and their families often feel overwhelmed.

“The model we chose was one that would be very personal,” said Dr. Eric Anderson, a palliative care physician at Allina’s United Hospital and one of the LifeCourse leaders. “There is an intimate connection between talking about what matters most and having effective advanced directives.”

In some ways, the program turns the patient’s focus away from the end of life to the life that can be lived.

“People want to have meaning in their lives, that is more important than anything else,” said Anderson.

“The lived experience for these patients and for their families is simply better. In a number of ways they feel more holistically supported, less anxious and they are using services in a more rational and effective way.”

Minneapolis-based Allina is so encouraged by the program that it plans to develop it beyond the research phase and make it available to patients at eight Allina clinics by the end of this year. It is also talking with other organizations that might adopt the LifeCourse model.

“We’ve got such a large number of people who will be over the age of 65 who will face serious illness,” said Heather Britt, Allina’s director of applied research, who also worked on the project. “Systems like ours have to figure out what to do differently.”

Setting a course

LifeCourse began in 2012, targeting patients with heart failure, advanced cancers and dementia using Allina’s electronic medical record.

“We figured out who was sick enough with those diagnoses, and that took a fair amount of tweaking,” Anderson said.

Eventually, 450 patients were enrolled in the intervention group and about an equal number in a control group.

Care guides meet with patients and their families monthly.

“I am helping them identify what their goals would be and what resources that they might need,” said Judi Blomberg, an Allina care guide since 2013. A lawyer by training, Blomberg was drawn to a health care job because she wanted to help people dealing with crises and trauma.

“Feeling overwhelmed is something that happens when we hit those crisis points,” said Blomberg. “One of my jobs is to help people anticipate what is to come.”

Using a set of questionnaires and assessment tools, care guides help patients set a course to achieve what matters to them.

For some patients, it could be medical goals such as staying out of the nursing home, controlling blood sugar, walking without a cane or losing weight. But many patients also set goals outside the medical realm: doing volunteer work, spending more time with relatives or putting together photo albums.

Toes in the ocean

Bob DeMarce and his wife, Marilyn, who were among Blomberg’s first clients, decided their initial goal was to develop a living will.

“One thing that we were bringing to them was a framework where they can talk about difficult things together that had been hard for them to talk with each other about,” Blomberg said.

“It felt very natural,” said Marilyn DeMarce. “They made it not hard to sit down and have a conversation.”

“She kept us on point and made sure we got it done,” said Bob DeMarce, who does not want any extraordinary measures to prolong his life.

In addition to completing a living will, the DeMarces resumed traveling, a favorite pastime, last November with a trip to Palm Springs, Calif., including a side trip so Bob could stand in the ocean.

“That was big on my bucket list,” he said.

Although Bob DeMarce is now cancer-free, he did fall and break his femur about two years ago. The DeMarces were able to rely on their care guide for help.

“It really provides extra support. When you are in crisis you need as much help as you can [get],” said Marilyn DeMarce. “When you are living with this type of illness you know that at any moment your life could just change.”

“The interest they have shown in my health for whatever reason has been beneficial to me,” Bob DeMarce said. “It prepares you to live with being sick but it also helps you to get ready to die.”

Complete Article HERE!