— Chaplains give terminal COVID patients a chance to say goodbye

By Will Peebles

Two days after a parade-less St. Patrick’s Day in Savannah last year, Mayor Van Johnson declared a local state of emergency because of COVID-19. The next day, March 20, the Georgia Department of Public Health reported the first two cases of COVID-19 in Chatham County. In the year since, Chatham County has lost more than 350 people to the virus. This article is one in a series that examines how individuals have dealt with a year-long crisis and have helped pull the community through the pandemic.

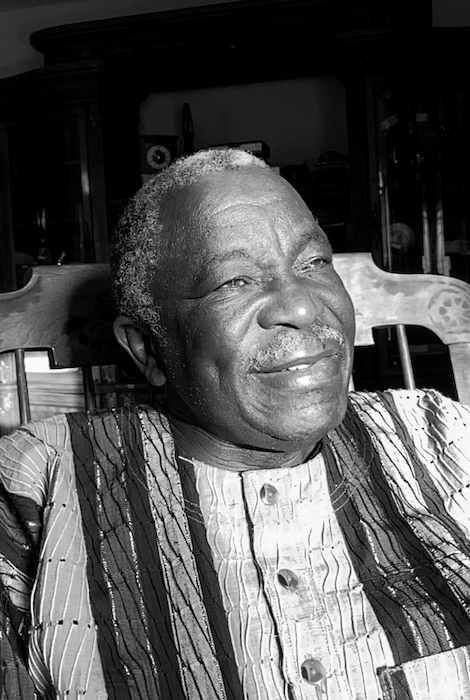

Rachel Greiner remembers when the reality of COVID-19 truly hit home for her.

In June, Greiner, the director of Memorial Health University Medical Center’s Pastoral Care team, found herself making arrangements for a mother and daughter, both sick in the hospital with COVID.

The daughter, the more serious case, was on the hospital’s COVID intensive care unitfloor.

She was dying.

Her mother was on the floor above her, reserved for patients sick enough to be in the hospital, but not yet sick enough to require ICU care.

Greiner and her staff of chaplains worked to get the mother into her daughter’s room. They were together until her final breath, a powerful, truly human moment — a final goodbye.

“And it was, of course, a sacred time, very beautiful that the hospital worked in order to get this woman down to be with her daughter,” Greiner said. “And while that was happening, my phone was ringing, and it must have rang six times.”

While Greiner was making sure a mother could be there with her dying daughter, her own children’s daycare was calling. She stepped out, in full personal protective equipment, to return the missed calls.

The daycare told her one of the teachers contracted COVID, and was calling to tell Greiner her children had been exposed.

“Now, that’s so commonplace I would roll my eyes if they called me and told me that today, but at that juncture, literally standing at the deathbed of someone with COVID-19, hearing that my children had been exposed to it — that was probably the moment that I was like okay, this is really real now,” Greiner said.

As a chaplain, Greiner deals with heart-wrenching situations on a daily basis. And for the last year, there has been no shortage of difficult work.

It’s a misunderstood profession, Greiner said. She and her team provide spiritual care to patients in the hospital, but it isn’t a single religion — in fact, it’s not inherently religious at all.

“We call it a ministry of presence. Sure, a lot of the things that we do are religious in nature. People want to pray. And they ask, and of course, we say yes,” Greiner said. “But we don’t come in the room demanding that you bow your heads and pray with us.”

If a person is in the ICU at Memorial Health, they’re going to see a chaplain at least once during their stay. But COVID, as it so often does, complicates things.

Early on in the pandemic, Memorial turned an entire medical ICU into an ICU specifically for COVID patients. Nurses were sending their children to live with grandparents to avoid possible spread.

Chaplains are in charge of facilitating patient visits. Sometimes those visits are virtual — they hold an iPad with family members on video chat. Not long ago, Greiner did a call with 48 people as they said goodbye to a family matriarch.

But it’s not the same.

“There’s no substituting what it would be for these patients to hold the hands of their spouses or their children. But in their stead, I will hold their hands and hold the iPad over them so that their loved ones can say goodbye,” Greiner said. “And my hope is that as they are transitioning from this place to the next, that that’s what they’re hearing: the love pouring out of their family’s voices coming through the iPad to them.”

For in-person visits in the COVID ICU, adults get one visitor. For kids, it’s two.

But when they’re moved to end-of-life care, that number is expanded to five.

That’s a tough restriction for some families. Only two people can go to be with their dying loved one for 30 minutes at a time.

“Let’s say it’s a spouse, they’ve been married 50 years, they have six kids. Well, they only have four more spots left, so they have to pick their four favorite children. And then of those four, only one of them can stay with dad while mom dies,” Greiner said. “I understand the reasoning behind it. But it is no less difficult to explain over and over again, and to empathize and say how sorry you are that you can’t get everybody in.”

It can be exhausting, but Greiner’s job doesn’t stop there. Her pastoral team members aren’t the only ones putting in emotional work day after day: the nurses, doctors and staff at Memorial are in the thick of the pandemic, as well.

Greiner said while her job is patient-oriented by nature, a lot of her work involves caring for her coworkers, as well. She coordinates with Memorial’s Nurse Manager Amber Schieber to host Muffins, Moments and More, a get-together at the hospital where the staff leans on each other for support, talking through situations that affected them, Schieber said.

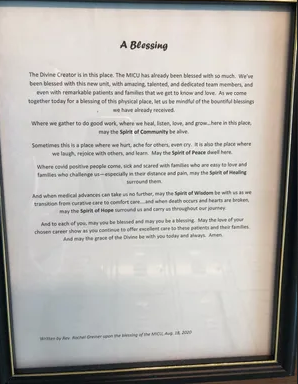

In the breakroom is a prayer, written by Greiner, framed by Schieber.

“Rachel has really been a rock for us during this pandemic. She’s so wonderful. She’s been there for our patients and the families and the staff,” Schieber said. ”If COVID has taught us anything, it’s to really lean on your family and your support system. And Rachel has absolutely been that for us.”

“I tell everyone, it is so important to establish a counselor of some sort, especially when you work in health care,” Greiner said. “You can’t care for other people if you’re not caring for yourself.”

For Greiner, self-care is paramount. It can take the form of a monthly check-in with a therapist or a pep talk from her family. Sometimes, it’s as simple as getting out of the house to go to her happy place: the beach.

“I have a family that supports me, my husband knows if I say it’s time to go to the beach, then it’s time to go to the beach,” Greiner said.

The emotional toll of her job is enormous, and it has been especially so for the last year. But day-in and day-out, she facilitates these sacred end-of-life rituals — these final goodbyes — for those most touched by the tragedy of COVID.

“It is difficult, but it’s also very humbling. I think that the ground we stand on at that point is very sacred, and it’s an honor to stand on it with these people and to help bridge the gap from wherever their families are to that room where they can’t be,” Greiner said. “To hold their hands and stroke their faces and tell them it’s going to be okay as they leave, it is an honor.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!