A federal appeals court ruling in favor of Benedictine monks who had been blocked from selling their handmade caskets by Louisiana’s state funeral board “is a victory for the monks as well as for free enterprise and entrepreneurs” in the state, their lawyer said.

“And it puts a nail in the coffin of the casket cartel,” said Darpana Sheth, an attorney with the Arlington, Va.-based Institute for Justice, which represented the monks pro bono in the case.

In a unanimous opinion, the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled Oct. 24 that a five-year battle by the Louisiana State Board of Embalmers and Funeral Directors to stop the Benedictine monks of St. Joseph Abbey in St. Benedict, La., from selling handmade, cypress caskets was either unconstitutional or unauthorized by Louisiana law.

The only question remaining to be determined by the three-judge appeals court panel was a legal technicality, Sheth told the Clarion Herald, newspaper of the New Orleans Archdiocese. The 5th Circuit asked the Louisiana Supreme Court to determine by January if state law authorized the state funeral board to regulate casket sales.

The law requires any business selling caskets in Louisiana to be a licensed funeral home that employs a funeral director and has a casket showroom. The monks twice had gone to the Louisiana Legislature to amend the law, but those bills never got out of committee, so they filed a lawsuit in 2010.

“The court, out of an abundance of caution, wanted to make sure before it rules on constitutional grounds that the state board could even regulate the sale of caskets when that’s all someone (such as the monks) does,” Sheth said. “In its opinion, the 5th Circuit said very strongly they can’t find any reason to uphold the constitutionality of the law. The court rejected all the arguments put forward by the state board in support of constitutionality.”

“It’s a win-win for us, as well as an answer to our prayers,” said Benedictine Abbot Justin Brown. “It also confirms the feelings we’ve had all along that this was the right thing to do. We had a right to sell our caskets, and the courts are upholding that right.”

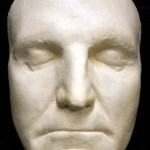

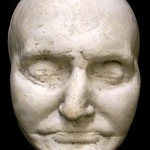

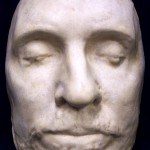

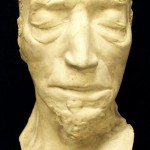

The Benedictines of St. Joseph Abbey have made the caskets for decades to bury their brother monks, but public interest in the caskets began in the early 1990s and has grown over the years.

In 2007, the Benedictines launched St. Joseph Abbey Woodworks, headed by Deacon Mark Coudrain, a master woodworker, to begin making caskets to sell to the public.

The Louisiana State Board of Embalmers and Funeral Directors presented the monks with “a cease and desist” order, which led to the monks’ ultimately unsuccessful efforts to get recourse from the Legislature and their lawsuit.

In 2011, the monks received a favorable ruling from U.S. District Court Judge Stanwood Duval, who struck down the Louisiana law, saying it created an unfair industry monopoly.

The state funeral board appealed to the 5th Circuit, saying the law protected consumers by ensuring that any caskets sold were the right size to fit into Louisiana’s oddly shaped, above-ground crypts.

Deacon Coudrain said he was thrilled that “common sense” had prevailed in the 5th Circuit ruling. The woodworks project turns out about 20 cypress caskets a month, and all the notoriety the casket case has received has helped business.

“It doubled what we thought we would be selling,” Deacon Coudrain told the Clarion Herald. “Right now we’re selling about 20 a month. This is absolutely common sense. Common sense is what drove us to this point to say that this didn’t make any sense and was really an injustice to the monastery.”

The deacon said the support the monks have received across the state has been encouraging.

“Monasteries are not known for suing states, you know?” he said. “We’ve gotten excellent feedback. We’ve had people buy caskets just because they’re so angry that others are trying to stop us. We’ve also gotten a lot of good feedback from funeral directors. A lot of them were very supportive and helped us out.”

Deacon Coudrain said several monks and volunteers were hard at work making the caskets when they got word of the court decision.

“We’re free to pray and to offer prayers of thanksgiving,” Deacon Coudrain said. “We can also pray for those we are making the caskets for. We’re just a bit freer to do that now. That’s what we do when we’re making the caskets — pray for those we are making the caskets for.”

The federal case will be stayed pending an answer from the Louisiana Supreme Court on the question that the 5th Circuit posed. The appeals court set Jan. 22, 2013, as a follow-up deadline.

Complete Article HERE!