Delivering cremated remains to the stratosphere joins a growing list of new ways to memorialize the dead.

By Marina Koren

[M]ark Harris says funeral directors talk about it all the time. More and more people are growing tired of traditional funeral services and opting for something a little more creative. “It’s getting more difficult to offer the cookie-cutter send-off,” explains Harris, the author of Grave Matters, which examines how people have started to think, er, outside the box about death.

And so, Harris wasn’t surprised to hear that a new British company is offering to send cremated remains to the stratosphere. High-altitude latex balloons will float to 100,000 feet above the surface of the Earth, where the curvature of the planet appears against the darkness of space, and then release the ashes into the cold, creating a glittering display. “Scatter your loved one’s ashes in space,” Ascension Flights says on its website. “We are all made of stardust.” The stratosphere is not technically space, but for their purposes, it’s close enough.

Ascension Flights, run by funeral directors and a near-space launch firm, will soon offer its high-altitude funerals, with the cheapest package starting at £795, or about $1,040. For more money, customers can choose the launch site and have the scattering photographed and filmed

The near-space funeral is, at first glance, a contrast to “green” burials, which return remains to the soil in biodegradable coffins or urns. In this way, the deceased can meet “the green reaper,” as a Guardian article in 2014 colorfully put it, and contribute to the physical processes of the Earth. Blasting ashes into the stratosphere sure sounds like the opposite of that, but Ascension Flights promises some kind of return to the planet. “As the particles eventually return to Earth, precipitation will form around them, creating raindrops and snowflakes,” its website explains. “Small amounts of nutritious chemicals will stimulate plant growth wherever it lands.”

Harris, who favors going the natural route, said this promise seems considerably less certain than that of green burials, where at least “I wouldn’t have to worry about having my loved one’s ashes raining down from space on some random location like a landfill or a Superfund site or a nuclear power plant,” he said.

Both kinds of memorials are part of the same growing trend in end-of-life affairs, Harris said. People are becoming increasingly interested in how their physical remains, and the remains of their loved ones, will be handled. They want something more personal and more personalized.

These days, people can forgo metal caskets and be buried in bamboo or recycled cardboard instead, or have their remains wrapped in banana leaf, cotton, or wool. A company called Eternal Reefs will fashion an environmentally friendly artificial reef out of cremains—cremated remains—and drop it into the ocean for nearby marine life to populate. Cremains can be pressed into diamonds, incorporated into paint, and ejected as fireworks. The variety of options for the dead reflects the consumer culture of the living, says Phil Olson, a Virginia Tech professor who studies funeral practices, like the home-burial movement. “There are at least seven kinds of Coke, 500 kinds of cigarettes—options, options, options,” Olson said. Consumers want just as many choices in death as in life.

The option to send a loved one’s ashes to actual space has existed for several years already, for a steeper price than Ascension Flights charges. Since 1997, the company Celestis has flown missions into space delivering the cremains of dozens of people, including Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry. The payload is launched inside a capsule to more than 300,000 feet, beyond the boundary of space, and eventually falls back to Earth.

While the concept of commemorating life’s final frontier in the final frontier may seem incredibly high-tech, the emotion behind it is no different than run-of-the-mill funerals on Earth. Funeral services can be, in the end, more for the benefit of those who are left behind than those who’ve passed away. They are about processing grief, and grief is personal. For some, the thought of sending their loved one’s ashes into the stratosphere is, simply, very fitting, and it’s difficult to pin down the exact reasons why.

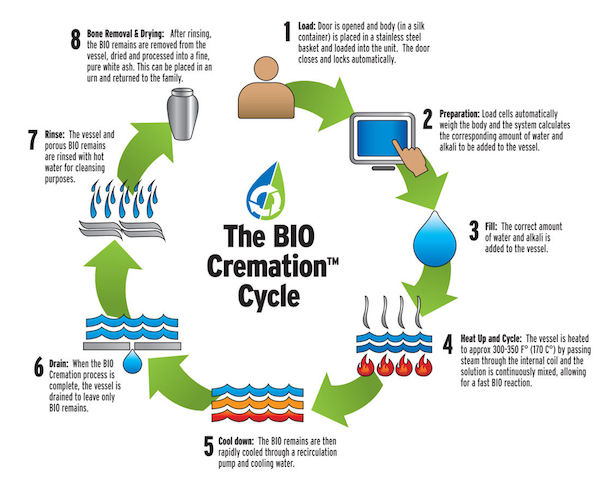

Olson points to alkaline hydrolysis as an example of the funeral industry misunderstanding its customers. Providers of alkaline hydrolysis, which reduces bodies to skeletons in a liquid solution, believed the appeal of the process came from its eco-friendliness. They later found that the primary reason people gave for choosing hydrolysis was that they perceived it to be gentler than cremation. “For some reason, people see being dissolved in caustic alkaline as being gentler than being incinerated,” Olson said.

Perhaps having more options to memorialize the dead may ease the grieving process in some way, he said, even if it’s not clear exactly how.

“We can speculate all we want for people’s motivations for doing this, but we could be dead wrong,” Olson said of the high-altitude memorial and, when I laughed in response, quickly realized his choice of words. “Sorry, pardon the pun. I didn’t even notice that.”