[F]orget long-faced funeral celebrants and bodies in their Sunday best – the ‘death positive movement’ is shaking up the way we die.

My grandma was 93 years and nine days when she died in April. She’d had a long and good life but her final years were severely compromised. By the end, she could neither walk nor feed herself, she could barely hear and most of the time she did not know who we were. Her world had shrunk to the size of her room. Then it shrunk some more, to the size of her bed. Was she happy? I don’t know. But I can’t imagine that this was the ending that she had in mind.

Dying used to be a typically brief process. Up until our most recent history, if you survived childhood illness, childbirth, plagues and famine, you generally got sick and then you died – often just days or weeks later. In the absence of today’s scans, tests, and life-prolonging drugs, by the time a person was really feeling poorly, their disease was advanced and they succumbed quickly. People died at home, families cared for the body, death was common.

Thanks to advances in modern science and economic growth, we are living longer than ever. In New Zealand, a female born in 1906 could expect to live till 66. Fast forward 100 years and a baby girl born in 2016 gained another 27 years, with a life expectancy of nearly 93. Now, for the majority of us the end comes after a long medical struggle (cancer and cardiovascular disease are our two biggest causes of death) or the combined debilities of very old age.

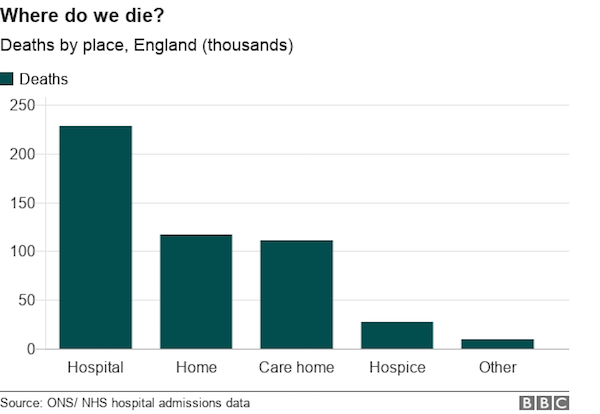

With a long life can come a long death, and over time we have unwittingly turned aging and dying into a medical experience. Our final stages have become largely obscured – even to ourselves – as we delegate death to the ‘professionals’. Today, it’s not uncommon for a recently deceased person to be collected from hospital or a rest home, taken to a funeral parlour where they are embalmed, washed, dressed and covered in make-up and kept there until the service, which might be conducted by a funeral celebrant who has never met the person they are speaking about.

The entire process is outsourced, sanitised and distant. As a result, we have become increasingly unfamiliar with death and consequently more frightened of it – particularly in Pākehā culture.

But a quiet revolution is taking place, according to many in the death industry. They’re calling it the ‘death positive movement’, and adherents say it’s about encouraging people to speak openly and frankly about death and dying, pursuing a “good death”, and pushing for more diversity in end of life care options.

Tea, cake and death talk

American mortician Caitlin Doughty, self-described “funeral industry rabble-rouser” and the person responsible for the phrase “death positive”, has found herself the face of the movement. In 2011 she founded the LA-based The Order of the Good Death, which describes itself as a group of funeral industry professionals, academics, and artists exploring ways to prepare a death phobic culture for their inevitable mortality.

A smell-of-death researcher, an end-of-life activist, a conservation burial pioneer and a grave garment designer are among some of The Order’s members. Doughty also runs Undertaking LA, a progressive funeral service whose emphasis is on placing the dying person and their family back in control of the dying process, including educating families on how to care for the dead at home.

She’s published a couple of books – a bestselling memoir Smoke Gets in Your Eyes: And Other Lessons from the Crematory, and From Here to Eternity: Traveling the World to Find the Good Death – while continuing to host her wildly popular ‘Ask a Mortician‘ YouTube series. Much of her time is now taken up with travelling the world speaking about the history of death culture and rituals, and working to address the death anxiety of modern secular culture.

Closer to home, Graham Southwell runs a monthly Death Café in the Waitakere suburb of Titirangi. Billed as an evening to drink tea, eat cake and talk death, Southwell says the aim is to raise awareness and get people to talk about death and dying. “It is like the last taboo. There is a great lack of understanding, a lack of knowledge, but also a huge fear around it. So when people can hear about good deaths, and some of the experiences people have had, I think it can be really helpful.”

The first Death Café (which is a not-for-profit social franchise, meaning anyone who signs up to the Death Cafe guide and principles, can host one) was held in London in 2011. They’re now popping up all over the world; currently there are 65 Death Cafés listed for New Zealand. Southwell, who has trained as a psychotherapist, has been running the Titirangi Death Café, together with celebrant Kerry-Ann Stanton, for the last three years.

He says their job is to act as facilitators and guide the group’s conversation in whichever direction they wish to go. Topics might include the meaning of life, grief, near death experiences and advanced care directives (a document detailing actions you want to be taken for your health if you are no longer able to make decisions because of illness or incapacity). “The idea is that if we start talking about death and dying it helps people to live more consciously, because it just puts everything in perspective.”

When asked whether he thinks New Zealanders are any good at dealing with death, Southwell, who is from the UK, mentions the tangi, the traditional Māori ceremony to mourn the dead. Usually held over three days, the body lies on a marae while people come to pay their respects. It is an occasion full of ritual and emotion, of oratory, song and storytelling. “They seem to have a very good way of dealing with death, that is rich and about celebrating someone’s life and I like that.”

DIY coffins

Every Wednesday morning on Rotorua’s north side of town, a crew of senior citizens gather together to catch up, connect, and construct their own coffins. They’ve been meeting like this since 2010, when former palliative care nurse Katie Williams launched the inaugural Kiwi Coffin Club in her garage, with no tools, no volunteers and no clue how to build a coffin. But after roping in some handy local men who helped with the carpentry, the club took off. Now there are around 200 members at clubs throughout the country.

If coffin construction isn’t your thing, for $350 you can purchase a ready-made one and go to town decorating it. But if you’re thinking of purple sparkles, or pictures of Elvis, or turning your coffin into a racing car with wheels fixed to the side, then I’m sorry to say someone’s beaten you to it. Of course, it’s not just the coffins people come for; it’s also for the safe and supportive space where death and loss can be discussed. The Rotorua club, who describe themselves as “Makers of Fine, Affordable Underground Furniture” also construct baby coffins for their local hospital and memory boxes, which they donate for free.

Death midwives

Death doula, deathwalker, death midwife, end-of-life midwife, soul midwife, companion to the dying. These are all names for the same role; someone who supports the dying and the grieving. And while it’s hardly a new concept – for thousands of years people have done this for one another – there is now an industry springing up to meet the demands of our increasingly secular and death-anxious population.

While death doulas can make a living from their work in the UK and the USA, here in New Zealand, those who are drawn to the role seem to be doing it on a volunteer basis. Strictly a non-medical role, a death doula might help to create a death plan, advocate on a person’s behalf, and provide spiritual, psychological and social support. They may also provide logistical support; helping with services, planning home funerals and guiding mourners in their rights and responsibilities in caring for someone who has died.

Carol Wales, who prefers to describe herself as a companion to the dying, has supported a number of people in their final weeks of life through her work as a volunteer at Auckland’s Amitabha Buddhist Hospice. Her role can be varied. She will visit the person in their home, take them out if they’re feeling up to it and offer massage and aromatherapy. “Some people want to talk about their life and what it means to them. That it does mean something. There might be issues with family members, siblings arguing about money, possessions. It can be very difficult for the person who’s dying to be in their process, because it is a process. Families can be protective, they can be in denial. One of the skills, I believe, is navigating all of that. Being on the periphery when you need to be, and being close to the person when you need to be. It’s like a dance.”

‘Nobody’s got out alive yet’

It’s a beautiful, still Wednesday morning at Dove House hospice in the Auckland suburb of Glendowie. A low-slung modest building, it’s hard to imagine that for some, this is where they come to spend their final days. Designed to support patients with life-threatening illnesses, and their families and caregivers, Dove House is based on a holistic model with a focus on empowering people to understand their own process and look for alternative ways of feeling better. It offers patients and their families counselling, support groups and workshops, as well as body therapies including aromatherapy, massage and reflexology.

Dove House’s doctor and medical counsellor Dr Graeme Kidd says while they do see extremely sick people at the end of their life, they also have a large number of patients who, despite being diagnosed with a terminal illness, may go on to live for a number of years. And while we’ve made huge scientific improvements in understanding diseases like cancer, Kidd, a GP for 40 years, thinks one of the key things missing in the medical model is humanity.

“A patient will finish their treatment and say ‘What do I do now?’ And the doctor will say, ‘Just get on with your life, be grateful you’ve got to a good place.’ And the patient’s thinking, ‘I was getting on with my life when this all happened, but now I’ve got this neon sign saying ‘I have cancer’. A common experience is being frightened of the diagnosis and feeling a victim of the illness, you feel diminished by what you’re living with. So it’s trying to reframe that; ‘You’ve had your treatments and you’re doing really well and how do we now get the rest of the show on the road?’ That there’s still a life to be lived.”

Kidd thinks we are getting better at death. “We’re certainly having some incredible experiences with families where it feels like the death is a positive experience, and people come out of it feeling almost proud of what they experienced. And to me, to experience death sets you up for your own process. Nobody’s got out alive yet and it’s a certainty that we’re all going there.”

Family involvement and personalisation

My grandma was very explicit about how she wanted to be farewelled; a cremation, specific locations to scatter her ashes, a small family-only gathering. No-one was to make a fuss. Her memorial service was two weeks after she passed, so that family coming from overseas could be there. It was a perfect autumn day, she would have approved. The service was held in a restaurant we knew she liked and there, we ate and drank and talked and laughed and remembered. Songs were sung, anybody who wished to say something could, and did. It was not in any way a sombre affair and collectively, as a family, we felt in control of the entire process. The only people that spoke of her knew her, had known her, our whole lives.

Chris Foote, owner of the Natural Funeral Company, says she is seeing many more of these types of services, like my grandmother’s, where the family opts to run it themselves, instead of using a celebrant. “People don’t like the idea that someone speaks about their person and doesn’t know them.” There’s a shift away from formality and tradition with many of their clients explicitly stating they don’t want religion and prayer to play any part in the service. Instead, “it’s just a whole bunch of people getting together and talking about that person and playing music.”

Increased family involvement is extending beyond the service, too. More families are wanting to assist with the washing, dressing and placing of the body in the casket, which Foote says they encourage. “We used to be community based around our care of the dead, we’ve gone away from that experience, and now we’re simply coming back to it.” She’s also witnessed an increase in families choosing to have the body at home until burial or cremation. In around a third of the deaths they deal with, she and her colleagues will make daily visits to a private residence to care for the body and keep it cool.

The Natural Funeral Company, as the name might suggest, specialises in natural organic body care. They do not embalm, a process involving the use of chemicals to preserve the body and forestall decomposition, instead they use essential oils, homemade restorative creams, minimal make-up and then ice bottles to keep the body cool. Most bodies can last around a week, although there are instances where things need to move reasonably quickly, and the odd occasion where they will recommend embalming. Says Foote: “Part of the reason that I don’t like to embalm is because I think we should see that natural process of the decay of the body. I think it’s quite a beautiful process actually.”

Self-expression in death, as in life, has become one of the hallmarks of our time. Where once our funerals followed the same format, now there is almost nothing that can’t be customised to reflect our personalities. There are legal requirements for paperwork to be completed, deaths to be notified and bodies disposed of, as for the rest it’s your party and you can do what you like.

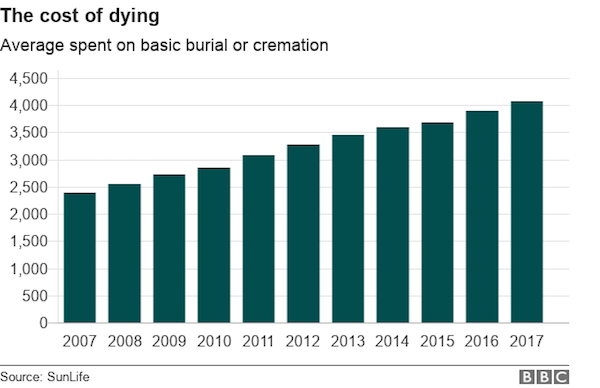

Fran Mitchell, co-founder of funeral home State of Grace, says the funerals they are involved with are all about best representing the person who has died; from coffins and venues to music and clothing. They are being held in all kinds of places; boat clubs, community halls, RSA’s, vineyards and people’s homes. “Wherever people had an association with, and not only in a church or a chapel where that person may never have gone.” The range of coffins on offer at State of Grace is staggering. From the Departure Lounge range, which includes floral designs and coastal sunsets, through to handwoven willow caskets, cardboard caskets, and simple calico shrouds. For the budget conscious, they can rent a coffin – and given the average New Zealand funeral costs around $10,000 that’s likely most of us.

Among their most popular coffins is a plain casket upon which families can write notes, draw pictures and fix photographs to. “It’s a really nice way to get the children and grandchildren involved. It can be quite therapeutic really.” Their range of urns is equally impressive; ceramic, wooden and hand painted.

As for coffin dress code? There isn’t one. Gone is the Sunday best, now people are putting their loved ones in whatever they think they’d be most comfortable in; pyjamas, no shoes, there aren’t any rules. They have had some people opt to wear nothing at all. Depart in the manner they arrived, you might say.

Mitchell is optimistic about the future of death. “I think things are changing for the better. People are talking about death more and accepting it as a part of life. Celebrating a life well lived instead of mourning a death.”

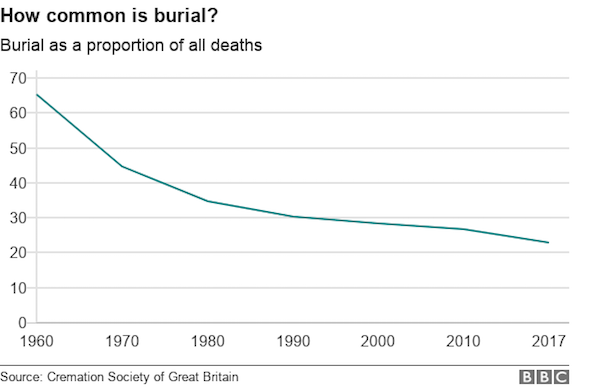

Body disposal: Mushroom death suits and sky burials

There are four options for body disposal in New Zealand. Cremation (70 per cent opt for this), burial, burial at sea and donating your body to medical science. But many are looking to alternative options. Recently, there’s been a growing demand for natural burials, which sees the body placed in a biodegradable casket or shroud and then into a shallow plot to allow for speedy decomposition (the body cannot be embalmed). The plot is then overplanted with native trees, a living memorial to those buried there. Currently, only a handful of councils in New Zealand offer natural burial sites.

Overseas, the death positive moment is actively endorsing more eco-friendly methods – some of which are still in development.

There’s liquid cremation (which involves dissolving the body, currently only legal in Australia and in eight US states), promession (freeze-drying the body, not yet legalised) and sky burial (a Tibetan funeral practice involving exposure of a dismembered corpse to scavenging vultures – very environmentally friendly). Finally, there’s the Mushroom Death Suit, an outfit embroidered with thread that has been infused with mushroom spores, which grow and digest the body as it decomposes following burial.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!