By TOM RACHMAN

A memoir of dying is exceptionally wrenching because we know the end at the beginning, and so meet with an effortful, pulsing person who will soon be neither. Pages rarely tremble with such life as when expressing their author’s death.

End-of-life memoirs have become increasingly prevalent of late. Christopher Hitchens wrote of his demise with customary pugnacity. Oliver Sacks recorded his fading remembrances, as did Tony Judt. Jenny Diski is currently chroniclingthe indignities of her last stretch, while Clive James composes newspaper columns on his future disappearance. Our aging population, granted so many extra years by medical science, anxiously tiptoes toward the dark matter, guided by those articulate enough, unlucky enough, to know what to say.

Often, the memoir starts with a prominent author declaring the diagnosis in a major periodical (Hitchens in Vanity Fair; Sacks in the Times; Diski in The London Review of Books). The diagnosis is usually terminal cancer, whose time frame may lend itself to contemplation, though not to more extensive pursuits. Typically, the author recites the markers of tragedy: foreboding symptoms overlooked, a collapse, the condemning scans, the switch to the wrong side of the window between healthy and ill. Some writers embody Hitchens’s line about “living dyingly,” straining to remain themselves, expressing dark humor and secular defiance, downshifting from existential fears to the banal process of death. Others pore over what they’ve had, been, seen. Touchingly, both Judt and Sacks cite nostalgia for gefilte fish. Food—that first pleasure—can be so important at the end, even when it cannot be swallowed.

Another mode is the lyric goodbye, typified by the poetry of James, particularly “Japanese Maple,” a rare popular hit for contemporary verse when it was published in The New Yorker. Of the maple tree, he wrote:

Come autumn and its leaves will turn to flame.

What I must do

Is live to see that. That will end the game

For me, though life continues all the same.

But a complication followed—among the only pleasant complications available to a terminal patient: James failed to die. Indeed, he continues to write, having survived that maple flaming twice over. In his new column for the Guardian, called “Reports of My Death,” he confesses to a twinge of embarrassment, as if he’d duped everyone with that guff about dropping dead. (A famous case of this desirable awkwardness involved the humorist Art Buchwald, who moved into a Washington hospice, in 2006, expecting to die, only to thrive there, dining on McDonald’s and holding court for months before ultimately moving back out.)

Other end-of-life writing is hortatory: memoirs with lesser literary aspirations but greater motivational ones, such as “The Last Lecture,” by Randy Pausch, a computer-science professor; the book, a parting address about achieving childhood dreams, was a best-seller. Another example is “Chasing Daylight: How My Forthcoming Death Transformed My Life,” by Eugene O’Kelly, an executive at the accounting firm KPMG who spent his final hundred days eschewing his hard-driving ambition in lieu of moral fulfillment. What most end-of-life memoirists share is a desire to wring the essence from what they’ve been—either to clasp on to it or, finally, to release it. These are works of defiance, sometimes escapism. Above all, they are expressions of the noble delusion: create because nobody endures, and create in order that you endure.

A compelling, crushing addition (and, sadly, a subtraction) is “When Breath Becomes Air,” by Paul Kalanithi, a neurosurgeon of immense promise who died of lung cancer, in March, at the age of thirty-seven, having labored on a memoir that stands as a manifesto for the genre, pressing readers to look at the impending darkness. “The fact of death is unsettling,” he writes. “Yet there is no other way to live.” When Kalanithi saw the CT scans of his chest, he surveyed a map of his own death. Others, including his shattered father, insisted that the young man would beat it. Kalanithi was too talented a diagnostician to concur. But a question pursued him: How long have I got left? This prompted a much shared Times Op-Ed that became the seed of his book.

In past centuries, those who were dying might have known that the end neared, but nobody had the tools to estimate when. Today, we have Kaplan-Meier survival curves, and yet doctors grow coy when pressed for a number. Keep up your hope! Kalanithi himself had dodged the subject with patients. When he becomes one himself, he aches to know. His oncologist refuses even to discuss it.

But it is time itself that conditions our behavior, even our identity. When we consider ancient populations whose life expectancy was less than forty years, we picture wretches, limited in scope, and fundamentally different from us as a result. Presumably, our descendants will view us in the same way, as being cursed with the appallingly brief span of eighty-something. For now, that is our anchoring point, an acceptable innings, with seventy too soon, sixty unfairly so, and so on. It’s a pact that the secular make with nothingness: we’ll accept just this life, but give us our share! While healthy, Kalanithi had divvied up his remaining years: twenty as a surgeon and scientist, followed by twenty as an author. Abruptly, he had to recalculate. If ten years remained, he’d devote himself to science. If two, he’d write. Which was it to be?

Raised in suburban New York, then in a small town in Arizona, Kalanithi was a bright son of southern-Indian immigrants, his father a cardiologist, his mother a trained physiologist, although she is recalled in his book more as her son’s minister for education. Her academic urging propelled him toward English literature at Stanford, which he studied along with human biology. At the graduate level, however, literary studies frustrated him, touching on the stuff of life, but with wool rather than with steel. The scalpel called. Soon, he was dissecting cadavers at Yale Medical School, where, he remembers, a surgeon drifted in to explain various scars on a corpse, his elbows leaning on the dead man’s face. Kalanithi returned to Stanford for his neurosurgical residency, and he excelled. He stood at the brink of a glittering career. But there was the weight loss, the back pain, the suspicions batted away. Chances are it’s just …

When the elderly face death, they dread losing what they’ve had. When the young face death, they dread losing what they haven’t had. Which is worse? Kalanithi’s wife worries that, if they conceive a child, it could render his farewell more excruciating. But life, he argues, is not about avoiding suffering.

Meds stabilize his disease for a spell. He soldiers through the completion of his residency. On a subsequent scan, a large new tumor appears. “I was neither angry nor scared. It simply was. It was a fact about the world, like the distance from the sun to the earth.” He conducts his last case as a doctor, his final walk from surgery, witnessing the dissolution of an identity so arduously attained. Kalanithi attended the birth of his newborn daughter, and grew deeply attached to her. “I hope I’ll live long enough that she has some memory of me.” Cady was eight months old when Kalanithi died. “Words,” he writes, “have a longevity I do not.”

The literary world has been circling the subject of death for at least a decade, notably via acclaimed accounts of bereavement such as Joan Didion’s “The Year of Magical Thinking” and “Blue Nights”; Kay Redfield Jamison’s “Nothing Was the Same”; and Joyce Carol Oates’s “A Widow’s Story.” Academic thinkers are joining in, too; among the volumes appearing this past year are “The Worm at the Core: On the Role of Death in Life,” by the psychology professors Sheldon Solomon, Jeff Greenberg, and Tom Pyszczynski; “The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains,” by Thomas W. Laqueur, a historian; and “The Black Mirror: Looking at Life Through Death,” by Raymond Tallis, a former professor of geriatrics.

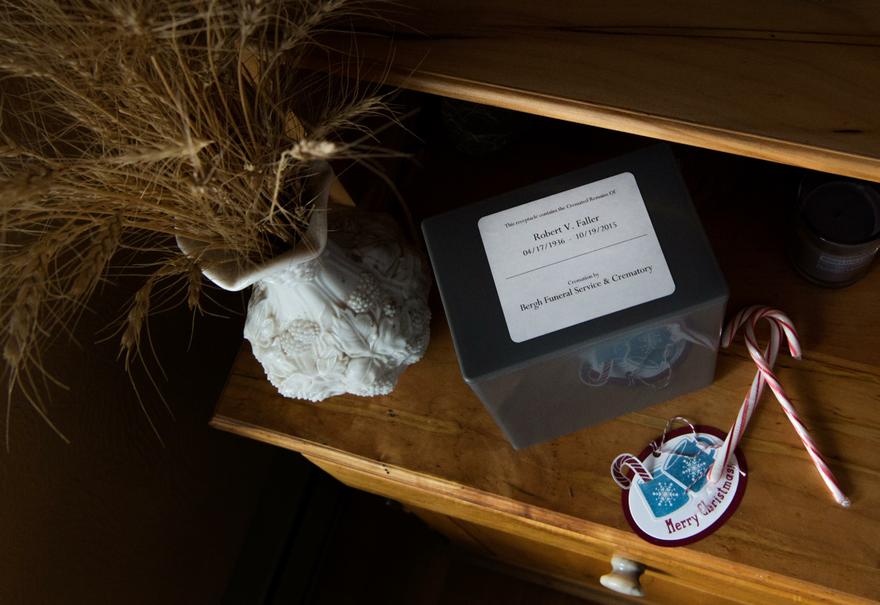

All this attention comes not from a greater understanding of mortality but from a greater ignorance of it. The promises of religion are replaced by the promise of science, yet medicine fails to vanquish its ultimate foe, instead rendering death more obscure, a matter for procrastination. The preëminent thanatophobe of our day, the novelist Julian Barnes, wrote a two-hundred-and-fifty-page memoir on his fear of nonexistence, “Nothing to Be Frightened Of.” The title isn’t intended to be soothing: by “nothing” he means “nothingness.” He writes, “If death ceased to be talked about when it first really began to be feared, and then more so when we started to live longer, it has also gone off the agenda because it has ceased to be there, with us, in the house.”

In richer parts of the world, death is likely to arrive in a nursing home, or in a hospital—precisely where we most dread spending our dwindling hours. The exit from life, as Atul Gawande observes in his treatise “Being Mortal,” has become overly medicalized in recent decades, causing us to forget centuries of wisdom. We have ended up with a system that treats the body while neglecting its occupant. But the discontent is mounting, Gawande says: “We’ve begun rejecting the institutionalized version of aging and death, but we’ve not yet established our new norm. We’re caught in a transitional phase.”

How much should each of us be pondering death? Some people flee the topic. (Few of them, I suspect, have read this far.) Others brood over it. As a matter of preparation, the death-minded aren’t necessarily better off, since they are so unlikely to predict their manner of departure. (How many flight-phobics will fall to earth clutching their chests?) Nor does one know the person to whom one’s own death will occur, given how the violence of disease changes a patient.

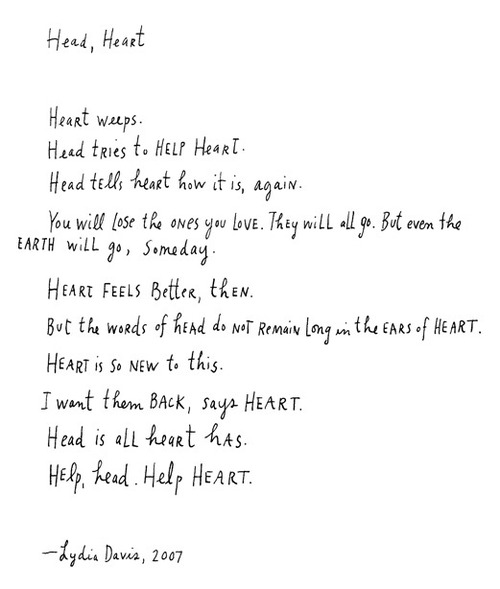

But death contemplation is more than prep work. It’s a world view, with nothingness conferring meaning on what precedes, just as a novel gains meaning from its conclusion and would lose sense were it to patter on interminably. Writers—perhaps from a vocational need for endings—seem especially attuned to the looming conclusion of themselves. Or maybe it’s the other way around: those gripped by thoughts of death are prone to artistic pursuits, in the hope that something of themselves will remain.

When medieval painters incorporated memento mori into their compositions—the skull dabbed into a portrait of courtly gents, say—they were proclaiming, “Beware earthly delights, for hell is everlasting!” In our times, the skull has become a fashion accessory or an attempt at irony in dreary artworks. The contemporary emblem of death is the bucket list, inverting the memento mori into “Partake of earthly delights, for life won’t be everlasting!”

The problem is not a lack of spirituality, though. The problem is how to partake of earthly delights. Should one engage in pleasures at the end? Should one strive for lasting accomplishment? The answer depends on what haunted Kalanithi: How long have I got? The answer is so hard to find, harder still to admit. Paradoxically, time is precisely where our society errs in handling death, having licensed our doctors to extend existence, irrespective of the character of the additional weeks. Unfortunately, dying is something we are figuring out only through doing. And now perhaps through the telling, too.

Complete Article HERE!