— OHSU School of Nursing alum aims to make end-of-life a social, not medical event

By Christi Richardson-Zboralski

As a hospice nurse, Erin Collins, M.N.E., RN, observed that many of her patients were afraid of dying, in denial of their imminent death, and consequently unprepared for it.

Now, she’s seeking to change that: Collins’ new organization, The Peaceful Presence Project, views compassionate end-of-life care as a basic human right, and is creating a social death care movement through education for clinicians, volunteer-based programs, and an innovative concept called end-of-life doulas.

“As health care providers, it is not always about saving lives at all costs, it’s about supporting someone to live and die well,” Collins said. “That often includes where they want to die and who they want to be present.”

Collins is a certified hospice and palliative care nurse with 16 years’ experience in oncology and end-of-life care. She recently completed a Master of Science in Nursing Education at the OHSU School of Nursing, Portland campus, and was selected as a 2022 Cambia Health Foundation Sojourns Scholar.

The mission of The Peaceful Presence Project is to reimagine the way communities talk about, plan for and experience serious and terminal illnesses. Its approach is based on the compassionate communities model of end-of-life care, which asserts people facing serious illness should spend 5% of their time with a health care professional, and views the end-of-life as a social event with a medical component — rather than the other way around. Their doula program helps fill the 95% of time people aren’t face-to-face with their health care provider.

Doulas are people who are trained to serve. Many people are familiar with birth and postpartum doulas, who serve families during and after the birth of a child. End-of-life or death doulas serve families during the end of the life cycle. End-of-life doula courses provide training in how to be a present and active listener; create a calm and compassionate environment; and provide non-medical comfort measures, such as distraction, guided imagery and repositioning to help alleviate symptoms. Trained volunteers may help with legacy projects, including collages, audio or video recordings, and other ways to display physical objects. When needed, they help with memorial planning.

The trainings emphasize how to facilitate compassionate discussions about death-related topics. In 2023, Collins will develop a continuing education program for rural health care workers through her Sojourns Scholar project to improve access to palliative care in communities where specialists often don’t exist.

Community-based end-of-life support

Lily Myers Kaplan speaks highly of The Peaceful Presence doula training she took in 2022. Meyers Kaplan is author of two books on loss and legacy, co-founder of The Spirit of Resh Foundation, the Ashland Death Café and The Living/Dying Alliance of Southern Oregon.

“There was a particular session on approaching end-of-life with veterans, which helped me see the need for diverse approaches to different populations. The difference in end-of-life support between those who have lived in a rural setting, caring for the land, or being actively reliant on their physicality versus someone who has had a more traditional or urban life is quite distinct.

“For example, caregivers who may be responsible for vast swaths of land — anywhere from 20 to 80 acres or more — need support from others who understand their needs,” said Myers Kaplan, who lives in the Applegate Valley, a rural area of Oregon that includes large stretches of land that provide solitude and a level of independence that most urban lifestyles don’t experience.

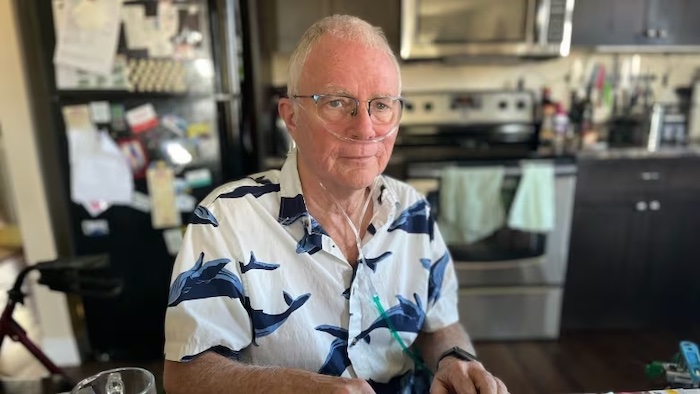

A caregiver in Depoe Bay reluctantly accepted help from The Peaceful Presence Project after his wife got him on board. After several long years of treatment and many ups and downs, Ray Burleigh’s adult daughter, Becky, had reached a point in her cancer treatment where it no longer worked. Burleigh had strong doubts when the hospice nurse brought up the topic. However, his wife, Jeni, said yes to the help.

With the support of two death doulas from The Peaceful Presence Project, Elizabeth and Erin, the Burleighs found some measure of relief. The death doulas told the family they would bring community support from around the Bend area.

“I was still not convinced. We needed practical help. Becky’s house is hard to heat and she was concerned they were spending too much money on keeping the house warm. It’s heated by a wood stove,” said Ray. “I told them to bring us some wood, not expecting anything. Two nights later, a truckload of wood came — not just one bundle, a truckload. I was shocked! We couldn’t have done this without Elizabeth and the doulas.”

Without the doulas’ help, Ray said they would have had to put Becky in the hospital, and possibly ended up sick themselves.

“The doulas provided night-shift help because we weren’t getting any sleep. They helped with groceries, created a schedule for visiting hours, and the fire,” he said.

Elizabeth and Erin identified 25 people in the city of Bend who were willing to help them out, including neighbors, and many people who are now friends of the Burleighs. Jeni’s family from the same area were also there to help.

Because of his time alongside these doulas, Ray has decided to take The Peaceful Presence Project doula training.

End-of-life care for under-resourced communities

Lora Munn, a yoga teacher who is National End-of-life Doula Alliance proficient, took The Peaceful Presence Project training in 2021.

“End-of-life care is not only being talked about in rural communities, but also actually being spread throughout rural communities thanks to the folks at The Peaceful Presence Project,” she said.

Munn lives in White Salmon, Washington, and serves all communities located in the Columbia River Gorge. She said she understands that “folks in rural and houseless communities may not have access to resources for the dying and their loved ones in the same way that urban communities do. Because of my education and training through The PPP, I am able to provide these necessary services to my small community. Through my training, I learned how to provide compassionate care for all beings, regardless of housing status or location.”

Because palliative and end-of-life care resources are sparse within rural and houseless communities, Collins and her team facilitate advance care planning to encourage these populations, and others, to think about their end-of-life experience.

“Parts of the state where there is no hospice care or even palliative care need more resources, and one way to address that is to have support embedded in the community,” Collins said.

Through two grant-funded projects, doulas and public health interns have been trained to hold advance care planning “pop-ups” at a navigation center for people experiencing homelessness, as well as in rural health clinics. Navigation centers are low-barrier emergency shelters that are open seven days per week and connect individuals and families with health services, permanent housing and public benefits.

Conversations about what their death experiences could entail are uncommon for people experiencing homelessness, Collins said. The general population tends to choose a spouse or family member as their medical decision-maker. But within the homeless population, a non-family member or someone in their so-called street family is more likely to be their choice. In the absence of a named decision-maker, the hospital may call an estranged family member or someone with whom they are not in contact.

“Equitable care means providing equitable services,” Collins said. “This includes advance care planning for people who are experiencing homelessness. We found that many of these folks have never been asked what their preferences are at end-of-life.”

Educating health care professionals about palliative care

Although it’s important to educate people in the community, it doesn’t stop there. Collins emphasizes the importance of education for all health professionals about serious and terminal illnesses — which is not traditionally an in-depth part of the health care curriculum.

“Nurses and physicians don’t always know how to have those conversations. Palliative care should be part of all health education,” Collins said. “Not just a specialty, but a standard part of education.”

To get participants thinking about ways to support their patients, The Peaceful Presence Project asks them to reflect on key questions: How do you ask someone about what they want if they are dying? How can you have a compassionate conversation?

“Training in communication skills allows you to feel empowered as a provider and as a fellow human being,” said Eriko Onishi, M.D., an assistant professor of family medicine in the OHSU School of Medicine and a palliative care physician at Salem Hospital. “It makes you a better listener through your professional sense of curiosity about other people. You feel as if you are truly walking alongside your patients, guiding them in the right direction, instead of just feeling the way blindly, guessing at each step.

“It’s important to understand that it isn’t about exercising power or control over patients,” Onishi continued. “Rather, it is using this powerful communication tool to support everyone involved, to help them to feel safe because the situation itself is under control.”

Onishi is passionate about the need for such conversation skills training.

“To be a clinician, both knowledge and communication skills are equally essential — it’s never a one-or-the-other choice,” Onishi said. “As a physician, my job is to provide medical guidance to the patient and their family, guided by the best intentions and a caring heart. If I cannot do all of these things, I cannot do my job.”

Ultimately, Collins said, it’s up to the individual patients to discuss how they want to experience their end-of-life, knowing that flexibility and adaptability are key. Having a plan is important, and when things don’t go according to plan, community-based support for death and dying can alleviate a stressful process for all involved — providing what people need to live and die well.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!