— He taught me to be more curious, present, and self-loving. His final lesson was more surprising.

By Christopher Fiorello

I woke up every thirty minutes the night before Ram Dass died. Stretching my perception through the big divider that separated his study—where I lay on a narrow couch—from his bedroom, I’d count the seconds between the short, ragged breaths churning through his sleep-apnea machine.

Four years later, I still have no idea why I was chosen to watch over him that night. I was at the bottom of the caregiver pecking order when it came to things directly related to Ram Dass’s body. I lacked the size and strength to transfer him from bed to wheelchair, or wheelchair to recliner, on my own; was too much of a novice to help organize his schedule or coördinate with his doctors; and was too unfamiliar to offer intellectual comfort in the rare moments that he wanted to talk. I’d met him ten months earlier, had his voice in my head for just three years. There were people in the house, on Maui, who had known him for more than three decades.

Before arriving, I had no formal medical training, but I had done three weeks of volunteering at a hospice facility in anticipation of coming to the island. Most of it involved moving Kleenex and changing the amount of light in empty rooms. Several times I sat with the dying. It was overwhelming to look at their closed eyes, feeling the heaviness in the room, the sense of something happening or about to happen. I scanned their faces for signs of pain, of fear or bliss, of transcendence. Through the palliative haze of opioids, they were impossible to read. No one was thrashing in pain; no one was smiling, either.

But it somehow buoyed me, being so close to death. The heaviness seemed critically important to my spiritual growth. I imagined myself giving peace to the dying through my presence, and in the process conquering my own fear of leaving life behind.

During my time with Ram Dass, I flitted constantly between self-righteousness and self-pity, one day indulging in grandiose fantasies that I was the heir to his legacy, charged with scattering his ashes, and the next imagining that everyone in the house hated me. The caregivers called it the classroom or the fire—a site of purifying work, a pathway to enlightenment.

My own work, purifying or otherwise, consisted mostly of handling various chores needed to keep a six-bedroom cliffside home with a pool, guesthouse, and two-acre yard going. For the bits that mattered—the scrubbing and the laundry and the cooking—there was a team of cleaners and a rotating cast of chefs. I ended up doing a lot of the rest: separating recycling, washing dishes, and replacing cat-scratched screens. There were three other caregivers in the house, and I was given a modest salary, plus my own room, meals, and shared access to a truck. I was an employee, but most days the house felt like a family, for better or worse.

Still, this was only the second time I’d been asked to spend the night in the study. It was generally perceived as an act of intense devotion: accepting a horrible night’s sleep, on a couch that reeked of cat pee, while facing the prospect of Ram Dass dying on your watch. I hated it, but I was there to care for the guy however it was decided that he needed care.

Most of the deciding was done by a woman affectionately dubbed Dassi Ma, a seventysomething lapsed-Catholic firecracker from Philadelphia. Dassi Ma was Ram Dass’s primary caretaker, and, though she no longer did the more strenuous physical tasks, she was still in command of what he got and when, often more so than Ram Dass himself. He was eighty-eight, and his health had been steadily deteriorating owing to a host of issues, including chronic infections. When I moved to Maui to be near him, in February, 2019, he had almost died the night I arrived. He bounced back, to everyone’s surprise but his own. “It wasn’t time,” I remember him saying in his stoic way, neither relieved nor disappointed. Now he had another spreading infection, and what appeared to be a cracked rib from being transferred to and from his wheelchair.

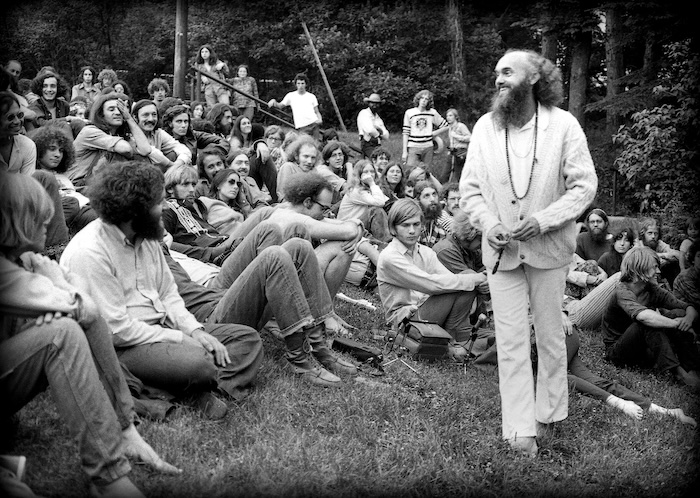

Ram Dass’s life is the subject of multiple documentaries, an autobiography, and a docuseries in development starring “High Maintenance” ’s Ben Sinclair. He was born Richard Alpert in 1931 to a wealthy Boston family. His pedigree was sterling: a Stanford psychology Ph.D., tenure track at Harvard, visiting professorship at Berkeley. In 1963, after five years at Harvard—much of it spent studying psychedelics with his fellow-psychologist Timothy Leary—he was fired for giving psilocybin mushrooms to an undergraduate.

He bopped around for a few years, often taking obscene amounts of mind-altering substances with Leary at the Hudson Valley estate of his friend Peggy Hitchcock. In 1967, like so many other Westerners of the time, he travelled to India in pursuit of exotic answers to life’s biggest questions. He’d grown disenchanted with the psychedelic world, which had come to seem rotely defined by highs and comedowns. In India, he met a Californian hippie named Kermit Riggs and followed him to a village called Kainchi, in the Himalayan foothills, to meet Riggs’s guru.

The guru was an old, squat man named Neem Karoli Baba. Before long, an enthralled Alpert was reborn as Ram Dass, or roughly “servant of God.” He returned to America later that year, arriving at the airport dressed in white robes and with a long, scraggly beard, and began his career as a spiritual teacher. Most of what he talked about, from 1967 to his death, were the experiences he had with Neem Karoli Baba, whom he called Maharaj-ji (“great king”), and the spiritual beliefs that emerged from those experiences.

One of his main ports of call became death and dying. In 1981, he co-founded the Dying Center, in Santa Fe, an organization that described itself as “the first place specifically created to support and guide its residents to a conscious death.” The center sought, in effect, dying people who wanted to use their death to become spiritually enlightened, and staff members who wanted to use other people’s deaths to achieve the same. Even before the Dying Center took shape, Ram Dass was lecturing on the spirituality of death, its place in the natural order, and the starkly contrasting way that he believed it was perceived in the East. His teachings were rooted in a specific vision of metaphysical reality, as informed by his guru and by the Bhagavad Gita, a sacred Hindu text. Roughly, he believed in nondualism, that there existed an unchanging and absolute entity—the Hindu Brahman, which Ram Dass more frequently called God, the divine, or oneness—from which all material reality came. Included in that reality were souls (something like the Hindu atman), which by their nature were caught in the illusion of their separateness from God, repeating a cycle of birth, suffering, death, and reincarnation until they remembered their true nature as part of the oneness—that is, until they became enlightened.

Death could be a crucial moment for remembering this nonduality, as it was when the “veil of separateness” was thinnest. In his 1971 book, “Be Here Now,” which has sold more than two million copies worldwide, Ram Dass summarizes his views: “You are eternal . . . There is no fear of death because / there is no death / it’s just a transformation / an illusion.”

He often spoke to crowds afraid of dying, repeating that he had “no fear of death.” He sat with people on their deathbeds and talked routinely about the power of “leaving the body,” his efforts to “quiet himself” so that the dying could see where they were in the reincarnation process and do what they could to escape it. His stories were sometimes graphic—people dying prematurely, or dying in tremendous pain—but always tinged with a lightness and humor.

Perhaps Ram Dass’s most memorable remarks about death came not from his own mind but from a woman named Pat Rodegast, who claimed she had channelled a spirit named Emmanuel from 1969 to her death, in 2012. Rodegast was working as a secretary, raising children, and practicing Transcendental Meditation when she began to see a light, which evolved into what she called telepathic auditory guidance. Some of that guidance was captured in three books published in the eighties and nineties, two of which came with forewords from Ram Dass. According to Ram Dass, when he asked Emmanuel what to tell people about death, Emmanuel replied that it was “absolutely safe,” “like taking off a tight shoe.”

I first encountered the voice of Ram Dass in 2016. I was twenty-seven and living in New York, in a Chinatown building that rattled every time an empty box truck drove down First Avenue. Each morning, I tumbled down five flights of sticky stairs and placed one of his talks deep into my ears, letting his distinct blend of scientific erudition and spiritual mysticism carry me across town.

He had a habit of segueing from psychological concepts, like attachment theory and childhood trauma, to cryptic ones, like Emmanuel’s messages and the astral plane, pausing briefly to ask listeners if they could really, truly “hear this.” He seemed to build on the insights of others who had revolutionized end-of-life care in America—thinkers such as the psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross—but also spoke in the New Age argot of Alan Watts. I gobbled it all up, feeling my spiritual life deepen exponentially by the day. His lectures made me more prosocial, more anti-capitalist, more curious, and decidedly more self-loving.

This was my second rodeo with spirituality; growing up, a rigid strain of Protestantism had been foisted on me like a chore. In Kansas City, Missouri, I was enveloped by an atmosphere of creationism, tent revivals, and anti-abortion screeds. I still recall standing on a busy street as a six-year-old and holding a sign that read “Before I Formed You in the Womb I Knew You—God.”

The teachings of Ram Dass were nothing like that. They were straight out of the hippie movement, and seemed to license a more liberal, self-directed search for meaning. As the grind and filth of Manhattan wore me down, Ram Dass’s voice became a salve, a way to “wake up to the illusion of our separateness.” I turned to his work again and again—to ease my loneliness when, walking down the street, droves of people moved around me like I was a light post, or to arrogantly tell my ex-girlfriend that we would always be “together,” even though I’d already dumped her.

After a couple of years, I learned that I could actually meet Ram Dass, for free, by signing up for one of his “Heart-to-Hearts”—a one-on-one, hour-long Skype call he offered as a sort of public service. When my time came, and the man appeared onscreen, I was stunned into silence. I had thought of him as a spry, ethereal figure who existed only in decades-old recordings. This Ram Dass was very old and lived with fairly advanced aphasia, a side effect of a major stroke he’d had in 1997. His speech was slow—in our full hour, he said roughly sixty words—but not at all ponderous. I thought it gave him a mystical quality.

There was no format to the session; Ram Dass just smiled his winning smile and listened. At one point, after I’d nervously overshared, he told me, “You take yourself pretty seriously.” That struck me as profound, at least at the time, but what endured was more feeling than words. It seemed he had arrived at a place from which he could find genuine love for strangers like me. It didn’t strike me as brand positioning, or as a form of ego; I didn’t think he loved me in the sense that he wanted to be close, or even that he cared whether we got to know each other. I just believed he saw me as another soul, and that, in his view, made me worthy of kindness.

By then, I was walking around New York, trying desperately to feel connected to anything. I wanted what Ram Dass had. So I left the city, intending, among other things, to get him to show me how to have it.

The friend I’d discovered Ram Dass with had already moved to Neem Karoli Baba’s temple, in Taos, New Mexico. I visited him for a fortnight of cooking group meals, wandering through the snowy high desert, and hobnobbing with Maharaj-ji zealots, including one white teen-ager who insisted that he was the reincarnation of Krishna, one of Hinduism’s most revered avatars. Like the young Krishna of lore, he would steal away to the temple pantry to eat pure butter until caught.

Some of this evoked my childhood church, where kids compared how quickly they could transition into speaking in tongues, or flexed the depth of their personal relationship with Jesus while leading a collective prayer. But this was my first encounter with Neem Karoli Baba devotees; I figured followers would be a bit more mellow the farther I got from his temple. Toward the end of my stay, I met a longtime friend of Ram Dass. He saw that I was eager to do volunteer work—known as seva, Sanskrit for “service”—so, when he learned of my intent to find Ram Dass on Maui, he offered to put in a good word to Dassi Ma.

That recommendation made the seemingly impossible possible. People of all ages came to the island to be near Ram Dass. Some found their way into the group texts for arranging kirtan—living-room chanting sessions at Ram Dass’s house—or beach excursions. A few found opportunities to be useful around the house, or made friends with one of the live-in caregivers, enabling them to drop by every week or so. But to be offered to help care for Ram Dass, for pay, as a virtual nobody, was exceptionally rare.

Upon arriving at the house, I found it shot through with the same quasi-religious fervor I had seen at the temple. I was quickly intercepted by another caregiver and taken to a lean-to, in a nearby pasture, so that I could silently meditate with prayer beads. It was incredibly humid, and I got annihilated by mosquitoes. I returned to the house to find a living room packed with people chanting—mostly the Hanuman Chalisa, a devotional hymn that features verses like “With the lustre of your vast sway, you are propitiated all over the universe.” A collective effervescence filled the room, and I joined along, staring at hundreds of statuettes of religious figures while fighting back the sense that I was in church.

After more than an hour of chanting, we milled about, greeting one another over chai and snacks. Attendees swapped stories of Maharaj-ji’s miracles, told me that my presence must be part of his plan, sat smiling at Ram Dass’s feet, their hands over their hearts. During my year on Maui, Ram Dass’s foundation led retreats at a local resort, where hundreds of people would gather for spiritual talks and chanting. Inevitably, someone at these events would look at me with confusion or pity when I told them my name was Christopher. “He hasn’t given you a name yet?” the person would ask. Ram Dass often bestowed a Hindu name on people: Lakshman, Govinda, Hari, Devi. I was fine with Christopher.

But there were other moments, informal and fleeting, when I witnessed the mixture of play and profundity that first drew me to Ram Dass. One autumn morning, two other caregivers and I were helping him get through his daily routine—brushing teeth and hair, putting on clothes and hearing aids, making the bed—when I turned on Doja Cat’s “Go to Town,” a song I later learned was about cunnilingus. I cranked the volume, and the four of us started dancing with illicit glee. One caregiver jumped on the bed, another swung from the divider between the bedroom and the study, and Ram Dass waved his one mobile hand with bright eyes and a rascally smile.

Another day, I was alone with Ram Dass, helping him pick out a shirt. Though I spent nearly all my time in the house, I could count the hours we had been alone together on two hands, and most of them had involved food and drink, or foot massages, ostensibly to relieve the pain that he felt from diabetic neuropathy. On this day, the house was recovering from Ram Dass having been denied psilocybin owing to his health. I felt sorrow for him; the drug was, after all, the beginning of his spiritual journey more than five decades prior. I asked him if the house ever felt like a prison. A full minute of silence passed, with me standing over him in his walk-in closet. Eventually, he tapped his temple and said, “This is the prison.”

When morning broke on December 22, 2019, and Ram Dass was still alive, I allowed myself a moment of relief. Dassi Ma came up, looking short on sleep, and took his vitals. They were horrible. We snapped into action, trying to comfort Ram Dass until one of his doctors arrived.

The infection had pooled fluid in his lungs, which made every breath a burden. Wet, rattling half-breaths were punctuated by coughs of bloody mucus. He looked wrecked, but still managed a weak smile when his Chinese-medicine doctor told a joke at his bedside.

At some point, Dassi Ma and the doctor began talking in the study; other caregivers were on an oxygen-tank-and-essentials supply run. I was on one side of Ram Dass’s bed; on the other was his longtime co-author Rameshwar Das, a friend since Kainchi. Then Ram Dass started choking.

It wasn’t that different from any of the other horrible breaths he’d taken that morning, except that he just couldn’t breathe it. When he realized this, he turned to me with a look that haunts me even now: light eyes wide as quarters, mouth open, lips a bit rounded. I immediately panicked, calling for Dassi Ma and trying to get his adjustable bed as upright as possible so that he could clear his throat. Then, when that didn’t seem upright enough, I frantically tried to lug his torso up so that his head could hang over his waist; perhaps he could vomit his throat clear.

Thirty seconds had passed since he first lost his breath. Somewhere from near his feet, the doctor snapped at me: “You have to calm down!” It jolted me into an awareness that Ram Dass was dying, right there. Perhaps it did the same for Dassi Ma, because she sprang for the study, returned with a large framed photo of Neem Karoli Baba, and commanded him to focus. “Ram Dass! Maharaj-ji! Maharaj-ji!” she said, placing the photo at the foot of the bed. She told him that she loved him, that he could go. I told him that I loved him. And then Ram Dass stopped trying to breathe.

I was the only person to leave the room. Stumbling into the study, I picked up my phone, hands quivering, and sent word to the other caregivers: “RD’s dying imminently. Like within the next couple of minutes.”

The wind was screaming outside. On Maui’s North Shore, it wasn’t unusual for it to reach thirty, forty knots, rattling the windows and throwing palm fronds across the lawn. That day, it had blown from early in the morning, under a tightly woven blanket of gray clouds. Sitting in the study, I watched it bend the trees, felt the violence of it, indiscriminate.

Ram Dass believed that fear kept us from recognizing our interconnection to all things. “Change generates fear; fear generates contraction; contraction generates prejudice, bigotry, and ultimately violence,” he said. In his teachings, he often placed fear and love on opposing sides of the human experience. Fear was the by-product of the ego; love was the by-product of the soul that remained pure, in the moment, especially at the time of death. “When we are fully present,” Ram Dass wrote, “there is no anticipatory fear or anxiety because we are just here and now, not in the future.”

And yet this binary is precisely what made watching him die so disorienting. I’ve no idea what Ram Dass felt in those final moments, what he could see or hear. I don’t even really know if that was fear I saw in his eyes, though it certainly looked like it. Perhaps it was surprise or another sensation entirely, the rush of emptiness before a huge plunge into something tremendous.

Whatever it was, its existence seemed largely absent from his teachings. There were times when he acknowledged the pain and coarse brutality of death. In his book “Still Here” (2000), he writes:

Dying is often not easy. the stoppage of circulation and starving of the heart muscle. the inadequate transport of oxygen to tissues, the failure of organs. Where can we hope to stand in our own consciousness during such traumatic conditions, in order to die with clarity and grace?

Yet the emphasis he placed, over decades of lectures, on the importance of grace during death made so little space for terror—for how fear could coexist with presence, and even with love. In the minutes after his passing, the chasm between how he died and how I thought he was supposed to die reminded me of the betrayal I’d felt when, at sixteen, I flouted my mother’s and pastor’s admonitions and stopped asking God for protection, only to discover that a similar slew of terrible and wonderful things still happened to me.

In the house, too, marching through three days of death rituals before Ram Dass’s body was removed, I felt my spirituality slip its moorings. Late on the second night, his body lay on ice in his study—a rite he’d specifically requested, hoping that it would help those around him transcend their fear. I sat on the floor and peered up at his face through candlelight, his skin whitish blue and gaunt, his mouth slightly agape. I waited for grace, for him to speak reassuringly from some other plane of reality. Instead, I was taken back to our final moments together, where fear sutured me to each passing second. Not fear of the past or some uncertain future, but fear of the vast, strange intensity of what is.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!