It’s been nearly two years since Colorado passed the End-of-Life Options Act. How has the controversial law affected Centennial Staters, and how, exactly, does one plan for a good death?

By Kasey Cordell

Merely Mortals

This is a story about death.

About how we in the United States—and maybe to a slightly lesser degree, here in Colorado and the West—tend to separate ourselves, emotionally and physically, from both the ugliness and the beauty of our inevitable ends. We don’t like to think about dying. We don’t like to deal with dying. And we certainly don’t like to talk about dying. Maybe that’s because acknowledging that human bodies are ephemeral short-circuits American brains groomed to (illogically) hope for a different outcome. Perhaps it’s also because the moment death becomes part of the public discourse, as it has in the Centennial State over the past several years, things can get uncomfortably personal and wildly contentious.

“As a society, we don’t do a great job of talking about being mortal. My secret hope is that this [new law] prompts talks about all options with dying.”

When Coloradans (with an assist from Compassion & Choices, a national nonprofit committed to expanding end-of-life options) got Proposition 106, aka the Colorado End-of-Life Options Act, on the ballot in 2016, there was plenty of pushback—from the Archdiocese of Denver, advocacy groups for the disabled, hospice directors, hospital administrators, and more physicians than one might think. But on November 8, 64.9 percent of voters OK’d the access-to-medical-aid-in-dying measure, making Colorado the fifth jurisdiction to approve the practice. (Oregon, California, Montana, Washington, Hawaii, Vermont, and Washington, D.C., have or are planning to enact similar laws.) Not everyone was happy, but if there’s one thing both opponents and supporters of the legislation can (mostly) agree on, it’s that the surrounding debate at least got people thinking about a very important part of life: death.

“As a society, we don’t do a great job of talking about being mortal,” says Dr. Dan Handel, a palliative medicine physician and the director of the medical-aid-in-dying service at Denver Health. “My secret hope is that this [new law] prompts talks about all options with dying.” We want to help get those conversations started. In the following pages, we explore everything from how to access the rights afforded in the Colorado End-of-Life Options Act to how we should reshape the ways we think about, plan for, and manage death. Why? “We’re all going to die,” says Dr. Cory Carroll, a Fort Collins family practice physician. “But in America, we have no idea what death is.” Our goal is to help you plan for a good death—whatever that means to you.

Death’s Having a Moment

Colorado’s end-of-life options legislation isn’t the only way in which Coloradans are taking charge of their own deaths. Some Centennial Staters have begun contemplating their ends with the help of death doulas. —Meghan Rabbitt

As the nation’s baby boomers age, our country is approaching a new milestone: more gravestones. Over the next few decades, deaths in America are projected to hit a historic high—more than 3.6 million by 2037, which is one million more RIPs than in 2015, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Here in Colorado, home to Boulder’s Conscious Dying Institute, there are a growing number of “death doulas” trained to help us cross over on our own terms.

Death doulas offer planning and emotional support to the dying and their loved ones, and since 2013, the Conscious Dying Institute has trained more than 750. Unlike doctors, nurses, hospice workers, and other palliative-care practitioners who treat the dying, death doulas don’t play a medical role. In much the same way that birth doulas help pregnant women develop and stick to birth plans, death doulas help their clients come up with arrangements for how they want to exit this life. That might mean talking about what projects feel important to finish (like writing that book) or helping someone make amends with estranged family members or friends or determining how much medication someone wants administered at the end. “When people are dying, they want to be heard,” says Nicole Matarazzo, a Boulder-based death doula. “If a doula is present, she’ll be able to fully show up for the person who’s dying—and model that presence for family members.”

Over the past year, the Conscious Dying Institute has seen a noticeable jump in the number of Coloradans using its directory of doulas and inquiring about training. When she started working in end-of-life care in 1998, founder Tarron Estes (pictured) says no one had heard of death doulas. Now she’s getting roughly 25 calls a week. “More people are getting comfortable talking about death,” Estes says. “In cities like Denver, there’s a willingness to talk about topics that are taboo in other areas of the country.” Medical aid in dying is, of course, a prime example.

That embrace of the end might be just another part of what is becoming known as the “death-positive movement.” More than 314,000 people have downloaded a free starter packet from the Conversation Project, a nonprofit that gets people talking about their end-of-life wishes. And more than 6,700 “death cafes,” where people gather to talk about death over tea and cake, have popped up around the nation, including several in Colorado. Ready to make a date with death? The Denver Metro Death Cafe’s next meeting is on October 20.

Knocking On A Death Doula’s Door

What to look for in an end-of-life guide.

1. Ask to see a certificate of education and research the organization that provided the doula’s training. Look for curricula that involve at least some in-person instruction. For example, the Conscious Dying Institute’s eight-day, on-site training portion includes lectures, writing exercises, demonstrations, and partner practices. It’s also split into a three-day session and a five-day session, with a 10-week internship requirement between each on-site phase.

2. Compare fees. Death doulas in Colorado charge about $25 to $125 an hour and may offer a sliding scale based on their clients’ financial means.

3. Pay attention to the doula’s listening skills. The last thing you want as you prepare to cross over is someone who hasn’t been hearing you all along.

Ink Your Legacy

If a good death includes making sure your family is cared for, one of the greatest favors you can do for your loved ones is to provide a clear path to all of your worldly possessions. Putting in the time—and paperwork—to plan for the dissemination of all your stuff can save your family months of headaches, heartaches, and contentious probate battles. Not sure what kind of estate planning documents you need? We spoke with Kevin Millard, a Denver-based estate planning attorney, to help you get started.

If you don’t you care about who gets your stuff…

Great; then you probably don’t need a will. If you don’t have a will, your stuff—cars, jewelry, artwork, etc.—goes to your closest relative(s) under what are known as “intestate succession laws” (the laws that govern how your stuff is divided after your death). The state maintains very specific equations for different scenarios. For instance, if you die with a spouse and children from a previous relationship, your spouse gets the first $150,000 of your intestate property plus half of the remaining balance, and the descendants get everything else. Or, if you die with a spouse and living parents, your partner gets the first $300,000 of your intestate property and three-quarters of anything over that. Your parents get

If you do care about who gets your stuff and some of your “stuff” is minor children…

At the very least, you need a guardian appointment document to determine who will care for your children after your death. Physical custody is different from managing any money you might have set aside for your children. You can name one person to manage the money and another to actually care for your children. Also, if your selected guardian doesn’t live where you do, he or she gets to decide whether or not your kids have to move.

If your most valuable stuff is not really “stuff” at all, but more like life insurance policies, 401(k) plans, bank accounts, etc…

Then you’ve probably already designated who gets what by appointing a beneficiary for those things. Anything with a beneficiary—life insurance policies, payable-upon-death bank accounts, retirement plans, or property held in joint tenancy (e.g., your house)—does not get distributed according to intestate succession laws (the laws that govern how your stuff is divided after your death if you don’t have a will). It goes to the listed beneficiary. However, you might want to consider also designating a durable financial power of attorney to manage all of your accounts in the event you become incapacitated before you die. Ditto for a medical power of attorney.

If your stuff is worth millions…

In addition to a will, you should consider a trust. This can protect your estate from being included in lawsuits if you’re sued, and it can also ease some of the estate tax burden on your heirs. But if you’re worth millions, then you probably already have people on retainer who’ve told you this.

If your stuff isn’t worth millions…

You need a will if you want to make life easier for your heirs. (In Colorado, any estate valued at more than $65,000 must go through probate court—a process that takes many months to finalize because you cannot close an estate here until six months after a death certificate has been issued, which can take several days or even weeks.) The general rule in Colorado is that a will must be signed by two witnesses to be valid. If you go through the trouble of having it notarized, it becomes a self-proving will, which means the court doesn’t have to track down the witnesses to certify its validity. You can also handwrite and sign your will; that’s known as a holographic will and does not require witnesses—but it does come with a lot of hand cramps.

My Father’s Final Gift

When it came to preparing for the end of his life, my father planned for the worst, knowing that would be best for me. —Jerilyn Forsythe

It was June in Arizona, and it was hot inside my dad’s kitchen. The whole place  smelled musty, the way old cabins do, and I watched as a swath of sunlight coming through the window illuminated lazy plumes of dust. My thoughts felt as clouded and untethered as the drifting specks. I had flown in from Denver the day before and driven more than 100 miles from Phoenix to collect some of my father’s things and bring them to the hospital, where he lay in a medically induced coma.

smelled musty, the way old cabins do, and I watched as a swath of sunlight coming through the window illuminated lazy plumes of dust. My thoughts felt as clouded and untethered as the drifting specks. I had flown in from Denver the day before and driven more than 100 miles from Phoenix to collect some of my father’s things and bring them to the hospital, where he lay in a medically induced coma.

It had all happened so fast. I’d received a midnight call from a neurosurgeon in Phoenix—the same one who had done a fairly routine surgery to mend a break in my dad’s cervical spine a few weeks earlier. Somehow, the physician said, my father had accidentally undone the surgery, leaving two screws and a metal plate floating in his neck. The doctor explained that he had operated emergently on my dad, who would be under a heavy fentanyl drip—and a halo—until he stabilized.

Although my parents had been divorced since I was two years old, my mother was there to help me that afternoon in Dad’s cabin. Between coaching me through decisions like which of his T-shirts to pack and whether or not I should bring his reading glasses, she happened upon a navy blue three-ring binder, with a cover page that read “Last Will and Testament, Power of Attorney & Living Will for Larry Forsythe,” in his bedroom.

He had never told me about the binder, but my name graced nearly every page within it. On a durable financial power of attorney. On a durable medical power of attorney. On a living will. And on his last will and testament. My typically nonconformist dad had prepared a collection of legal files that would become my bible in the ensuing months.

During the roughly 16 weeks he was hospitalized, I would reread, reference, fax, scan, copy, and email those documents—particularly the powers of attorney—countless times. I also thought, on nearly as many occasions, how fortunate I was that my dad, who probably struggled to pay for a law firm to draw up the papers, had done so just a year before he was unexpectedly admitted to the hospital. Without his wishes committed to paper, I know I would not have been able to fully and confidently make decisions on his behalf. But, navy blue binder in hand, I was empowered to speak with authority to doctors, nurses, bank executives, and even the cable company, which would not have stopped the monthly payments that were dwindling his already heartbreakingly low bank account had I not been designated his financial power of attorney.

I always thought that having a sick or dying loved one meant hospital visits and flowers and tears—all of which is true—but I spent far more time on the phone with medical professionals, financial institutions, and social workers than I did crying. I imagine all of that strife would have been magnified dramatically had we not found that binder.

My dad died a year ago this month. His passing brought more challenges for me, but for a long time after, I silently thanked him for having the foresight to visit that estate planning law firm, for considering what I’d go through when he was no longer here. It was one of the last—and best—gifts he ever gave me.

Process Oriented

Navigating the myriad steps to legally access medical-aid-in-dying drugs can be an arduous undertaking already. Some obstacles, though, are making it even more frustrating for terminally ill patients and their families.

Step No. 1: Determine Eligibility

For a person to be eligible to receive care under the law, he or she must be 18 years or older; a resident of Colorado; terminally ill with six months or less to live; acting voluntarily; mentally capable of making medical decisions; and physically able to self-administer and ingest the lethal medications. All of these requirements must be documented by the patient and confirmed by the patient’s physician, who must agree to prescribe the medication.

Procedural Glitch: Because the law allows individual physicians to opt out of prescribing medical-aid-in-dying drugs for any reason and because some hospital systems and hospices have—in a potentially illegal move—decided not to allow their doctors to prescribe the meds, it is sometimes difficult for patients to find physicians willing to assist them.

Step No. 2: Present Oral And Written Requests

An individual must ask his or her physician for access to a medical-aid-in-dying prescription a total of three times. Two of the requests must be oral, in person, and separated by 15 days. The third must be written and comply with the conditions set in the law (signed and dated by the patient; signed by two witnesses who attest that the patient is mentally capable of making medical decisions, acting voluntarily, and not being coerced by anyone).

Procedural Glitch: Although mandatory waiting periods are required in all jurisdictions with medical-aid-in-dying laws, these requirements are especially challenging for patients in small towns or rural areas, where there might not be a doctor willing to participate for 100 miles. For terminally ill patients, making two long road trips to present oral requests can be next to impossible.

Step No. 3: Get A Referral To A Consulting Physician

The law requires that once a patient’s attending physician has received the appropriate requests and determined the patient has a terminal illness with a prognosis of less than six months to live, the doctor must refer the patient to another physician, who must agree with the diagnosis and prognosis as well as confirm that the patient is mentally capable, acting voluntarily, and not being coerced.

Procedural Glitch: Once again, difficulties with finding a willing physician can cause lengthy wait times.

Step No. 4: Fill The Prescription At A Pharmacy

Colorado’s medical-aid-in-dying law doesn’t stipulate which drug a physician must prescribe. There are multiple options, which your doctor should discuss with you. Depending on your insurance coverage (Medicare, Medicaid, and many insurance companies do not cover the drugs), as well as which hospital system your doctor works in, getting the medication can be as simple as filling a script for anything else.

Procedural Glitch: Not every hospital system will allow its on-site pharmacies to fill the prescriptions—HealthOne, for example, doesn’t. Corporate pharmacies, like Walgreens, and grocery-store-based pharmacies often will not fill or do not have the capability to fill the prescriptions. What’s more, Colorado pharmacists are able to opt out of filling the prescription for moral or religious reasons. That leaves doctors and patients in search of places to obtain the drugs once all of the other requirements have been fulfilled.

Step No. 5: Self-Administer The Medications

Although the time and place are mostly up to the patient, if he or she does decide to take the life-ending drugs, he or she must be physically able to do so independent of anyone else. Physical capability is something patients must consider, especially if their conditions are progressing quickly and could ultimately render them incapable of, for example, swallowing the medications.

Procedural Glitch: Depending on the drug that is prescribed and the pharmacy that fills it, patients and/or their families are sometimes put in the position of having to prepare the medication before it can be administered. Breaking open 100 tiny pill capsules and pouring the powder into a liquid can be taxing even under less stressful circumstances.

Step No. 6: Wait For The End

In most cases, medical-aid-in-dying patients fall asleep within minutes of drinking the medication and die within one to three hours. The law encourages doctors to tell their patients to have someone present when they ingest the lethal drugs.

Procedural Glitch: Although most doctors who prescribe the medication do not participate in the death, it is worth asking your physician or your hospice care organization in advance about what to do in the minutes immediately after your loved one has died at home, as 78.6 percent of Coloradans who received prescriptions for life-ending meds under the law and subsequently died (whether they ingested the drugs or not) did in 2017. Someone with the correct credentials will need to pronounce death and fill out the form necessary for a death certificate (cause of death is the underlying terminal illness, not death by suicide) before a funeral home can pick up the body.

Who’s In & Who’s Out?

A short breakdown of metro-area hospitals’ and health systems’ stances.

Completely Out

SCL Health

Centura Health

VA Eastern

Colorado Health Care System

Craig Hospital

In, With Caveats

HealthOne

Boulder Community Health

All In

Denver Health

UCHealth

Kaiser Permanente Colorado

Alternative Endings

An Oregon nonprofit is Colorado’s best aid-in-dying resource.

Although Oregon’s Compassion & Choices is best known here as the organization that helped push Proposition 106 onto Colorado’s November 2016 ballot, the nation’s oldest end-of-life-options nonprofit didn’t abandon the Centennial State after the initiative passed. “First, we help states enact the laws,” says Compassion & Choices’ Kat West, “then we stick around to help with implementation and make sure it’s successful.”

In Colorado, the rollout has been fairly fluid. Perfect? Certainly not. Fortunately, Compassion & Choices has been trying to smooth some of the wrinkles in the system. The biggest help so far might be its website. The nonprofit keeps its online content updated with everything a Coloradan needs to know about the state’s End-of-Life Options Act. Of particular note: the Find Care tool, which lists clinics and health systems that have adopted supportive policies, since finding participating physicians, hospitals, and pharmacies is still challenging. “Patients don’t have the time or energy to figure this out on their own,” West says. “We do it for them.”

Hospice Hurdles

Why some local hospices aren’t as involved in Colorado’s aid-in-dying process as you’d expect.

Despite what you might have heard, hospice is not a place where one goes to be euthanized. “That misconception is out there,” says Nate Lamkin, president of Pathways hospice in Northern Colorado. “We don’t want to perpetuate the thought that we’re in the business of putting people down. That’s not what we do.” That long-standing myth of hospice care is, in part, why many Colorado hospices have declined—potentially in violation of state law—to fully participate in the End-of-Life Options Act.

By and large, the mission of hospice—which is not necessarily a place, but a palliative approach to managing life-limiting illness—has always been to relieve patient suffering and to enhance quality of life without hastening or postponing death, Lamkin explains. “This law kind of goes in opposition to that ethos,” he says. To that end, like many other hospices, Pathways has taken a stance of neutrality: Pathways physicians cannot prescribe the life-ending medication, but the staff will support their patients—by attending deaths, by helping with documentation—who choose the option. “We are not participating by not prescribing,” Lamkin says. “But it is the law of the land, and we fully support those who choose medical aid in dying.”

Pathways is not alone in its abridged participation. Other large Front Range hospice care providers, like the Denver Hospice, have also either taken an arm’s-length stance on the practice or opted out entirely. End-of-life options advocacy nonprofit Compassion & Choices regards this as willful noncompliance, which could leave hospice providers exposed to legal action, especially considering that 92.9 percent of Colorado’s patients who died following the reception of a prescription for aid-in-dying meds in 2017 were using hospice care to ameliorate symptoms and make their deaths as comfortable as possible. But, says Compassion & Choices spokesperson Jessie Koerner, when hospices abstain from fully supporting medical aid in dying, it strips away Coloradans’ rights—rights to which the terminally ill are legally entitled.

Filling More Than Just Prescriptions

After spending years at a chain pharmacy, Denverite Dan Scales opened his own shop in Uptown so he could better serve his customers. 5280 spoke with him about being one of the few pharmacists in Colorado meeting the needs of medical-aid-in-dying patients.

5280: Of the roughly 70 medical-aid-in-dying prescriptions written in Colorado in 2017, Scales Pharmacy filled approximately 22 of them. Why so many?

Dan Scales: As a pharmacist, you have no obligation to fill a script that’s against your moral code. So there are many pharmacists who won’t fill the drugs. Also, many chain pharmacies—like Walgreens—don’t mix compounds, which means they can’t make the drug cocktail a lot of physicians prescribe. That leaves independent pharmacies like ours.

You don’t have any objections to the state’s End-of-Life Options Act?

I really believe we kinda drop the ball at the end of life. We do a poor job of allowing people to pass with dignity. I won’t lie, though: After filling the first couple of prescriptions, I did feel like I helped kill that person. I needed a drink. But talking with the families after helps.

You follow up with your patients’ families?

Yes. We ask them to call us after their loved one has passed. We want to know how it went, how the drugs worked, how long it took, was everything peaceful? I’d say about 30 percent call us to offer feedback. It helps us know how to better help the next person. You have to understand, this is not a normal prescription; we talk with these people a lot before we even hand them the drugs. We get to know them.

If you could change one thing about the process, what would it be?

It’s frustrating that there’s not more pharmacy participation in our state. We’re having to mail medications to the Western Slope because people can’t find the services they need.

Final Destination

She couldn’t travel with him this time, but a Lakewood woman supported her husband’s decision to go anyway.

They met online, way back in the fuzzy dial-up days of 1999. J and Susan* weren’t old, exactly, but at 50 and 49, respectively, they had both previously been married. They quickly learned they had a lot in common. They were both introverts. Each had an interest in photography. And they loved to travel, especially to far-flung places, like Antarctica. After about two years of dating, they got married in a courthouse in Denver. For the next 17 years, they saw the world together and were, Susan says, “a really great team.”

The team’s toughest test began in fall 2017. Susan says she should’ve known something was wrong when she asked J if he wanted to go on an Asia-Pacific cruise and he balked. Upon reflection, Susan realized J likely hadn’t been feeling well. “That hesitation was a clue,” she says. The diagnosis, which came in January 2018, was a devastating one: stage 3-plus esophageal cancer. It was, as Susan puts it, “a cancer with no happy ending.”

It would also be, Susan knew, a terribly difficult situation for J to manage. He had never been able to stand not being healthy; she was certain he wouldn’t tolerate being truly sick. And esophageal cancer makes one very, very sick. The tumors make swallowing food difficult, if not impossible. As a result, some sufferers lose weight at an uncontrollable clip. They can also experience chest pain and nasty bouts of acid reflux. J knew he was dying—and that he didn’t want to go on living if he could no longer shower or go to the bathroom alone or be reasonably mobile. He broached the topic of medical aid in dying with Susan in February. “Honestly, I had already thought about it,” she says, “so I told him I thought it was a great idea.”

As a Kaiser Permanente Colorado patient, J had access to—and full coverage for—the life-ending drugs. The process, Susan says, was lengthy but seamless. J got a prescription for secobarbital and pre-dose meds; they arrived by courier to their house in April. Having the drugs in hand gave J some peace. He wasn’t quite ready, but he knew he was in control of his own death. He would know it was time when he began to feel like his throat would be too tight to swallow the drugs—or when he became unable to care for himself.

That time came in late June. He was weakening, and he knew it. Having decided on a date, J had one last steak dinner with his family on the night before his death. “He was actually able to get a few bites down,” Susan says. “He was also able to have a nice, not-too-teary goodbye with his stepchildren. It was wonderful.”

Although she was immeasurably sad when she woke the next day, Susan says seeing the relief on J’s face that morning reinforced for her why medical-aid-in-dying laws are so important. She knew it was unequivocally the right decision for him—a solo trip into the unknown, but he was ready for it. At noon on June 25, J sat down on the couch and drank the secobarbital mixed with orange juice. “Then he hugged me,” Susan says, “and he said, ‘It’s working’ and fell asleep one minute later. It was really perfect. He did not suffer. It was all just like he wanted it.”

*Names have been altered to protect the family’s privacy.

Drug Stories

A numerical look at medical-aid-in-dying meds.

$3,000 to $5,000: Cost for a lethal dose of Seconal (secobarbital), one of the drugs doctors can prescribe. The price for the same amount of medication was less than $200 in 2009; the drugmaker has increased the cost dramatically since then. Many insurance companies will not cover the life-ending medication.

4: Drugs that pharmacists compound to make a lower-priced alternative to Seconal. The mixture of diazepam, morphine, digoxin, and propranolol, which is reportedly just as effective as Seconal, costs closer to $500 (pre-dose medications included).

5: Ounces of solution (drugs in powder form that are dissolved in a liquid) a medical-aid-in-dying patient must ingest within about five to 10 minutes.

2: Pre-dose medications—haloperidol to calm nerves and decrease nausea and metoclopramide to act as an anti-vomiting agent—patients usually take about an hour before ingesting the fatal drugs.

10 to 20: Minutes it typically takes after the meds are ingested for a patient to fall asleep; death generally follows within one to three hours.

Uncomfortable Silence

Just because roughly 65 percent of voters approved Colorado’s End-of-Life Options Act in 2016 doesn’t mean Centennial Staters are completely at ease with the idea of the big sleep. Just ask these health care professionals and death-industry veterans.

“In a perfect world, I think one should be with family at the end. There are benefits of sitting with a dying person. Compassion means ‘to suffer with.’ Sometimes that suffering isn’t physical; it’s emotional. A lot of healing can happen at the end.”

—Dr. Michelle Stanford, pediatrician, Centennial

“If people’s existential needs and pain are addressed—things they need to talk to their doctors and family about—natural death can be a beautiful thing. It doesn’t have to be scary. In American society, we don’t talk about death and dying. It’s because we fear it. We are afraid of the anticipated pain, of having to be cared for. In other cultures, there is more family support and there is no thought of being a burden. This is a part of life, part of what should naturally happen.”

—Dr. Thomas Perille, internal medicine, Denver

“Doctors don’t die like our patients do. We restrict health care at the end of our lives. My colleagues don’t do the intensive care unit and prolonged death. We, as doctors, are not doing a good job helping patients with this part of their lives. Dying in a hospital is the worst thing ever. There is an amazing difference dying at home around friends and family.”

—Dr. Cory Carroll, family practice physician, Fort Collins

“Most people are unprepared for what needs to happen when a death occurs. Those who choose to lean toward the pain with meaningful ritual or ceremony are the ones I see months later who are moving through this process toward healing. The ones who think that grief is something that occurs between our ears are the ones who struggle the most. Sadly, we live in a society and a culture where grieving and the authentic expression of emotion is sometimes looked down upon.”

—John Horan, president and CEO of Horan & McConaty Funeral Service, Denver

“We only die once, so let’s do it right. When death happens, whether it’s our own or a loved one or someone we know, it’s not just their death that we’re acknowledging, but it’s life that we are all acknowledging. I think it’s helpful and healthy to honor death because in doing so, we are helping to celebrate life.”

—Brian Henderson, funeral celebrant, Denver

63 Percentage of Americans, 18 years or older, who die in hospitals and other institutional settings, like long-term care facilities and hospices. In 1949, however, statistics show that only 49.5 percent of deaths occurred in institutions. Because death in the home has become more uncommon, experts say, few Americans have direct experience with the dying process and that separation has, in part, led us to fear, misunderstand, and essentially ignore the end of life as an important stage of life itself.

Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; American Psychological Association

Another Shoulder To Lean On

Front Range support groups that can make bereavement more bearable. —Will Jarvis

This two-therapist firm offers support sessions specifically for those in their 20s and 30s as well as an anticipatory grief gathering called Facing The Long Road. This latter group—which focuses on helping 19- to 36-year-olds manage the despair and caregiving duties that can come with having a parent with a terminal illness—zeroes in on a demographic whose busy lives often get in the way of their well-being. Cost: $35/session

The premise behind the Compassionate Friends, a 49-year-old international organization, is that only other bereaved parents can understand the pain of losing a child. Today, the group gathers parents, grandparents, and family members and encourages peer-to-peer healing in monthly sessions. Six Front Range chapters provide safe places for those struggling with loss to share coping mechanisms and ways to find a new normal.

Cost: Free

Childhood traumas, such as losing a sibling or a close relative, can be especially challenging to overcome. That’s why this nonprofit, housed two blocks from City Park, has trained clinicians on staff to help both children and families dealing with grief. Its 10-week structured programs put kids in groups of five to 10 other children, and the organization provides a free dinner before each weekly meeting—giving anguished families one less thing to worry about.

Cost: Free

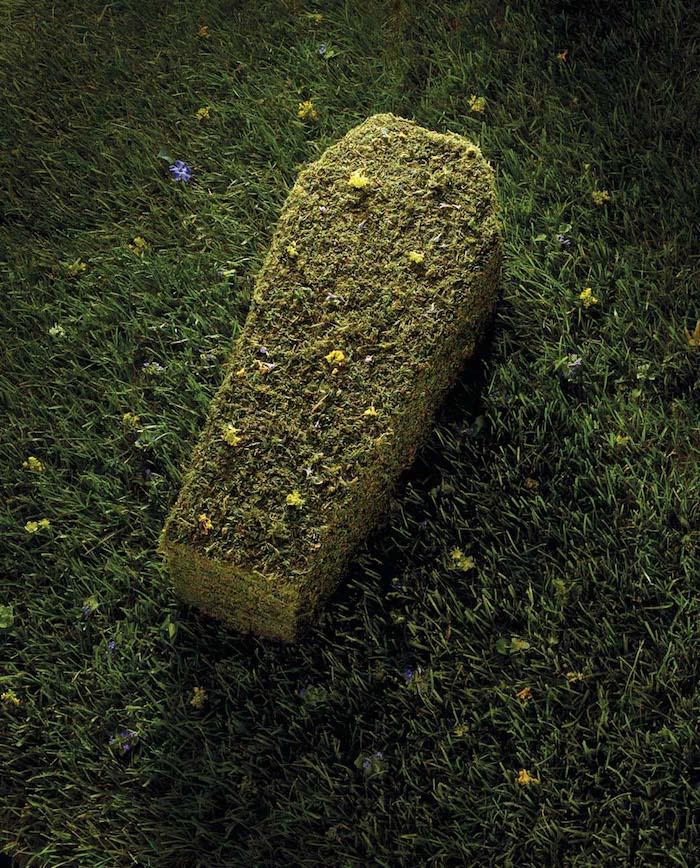

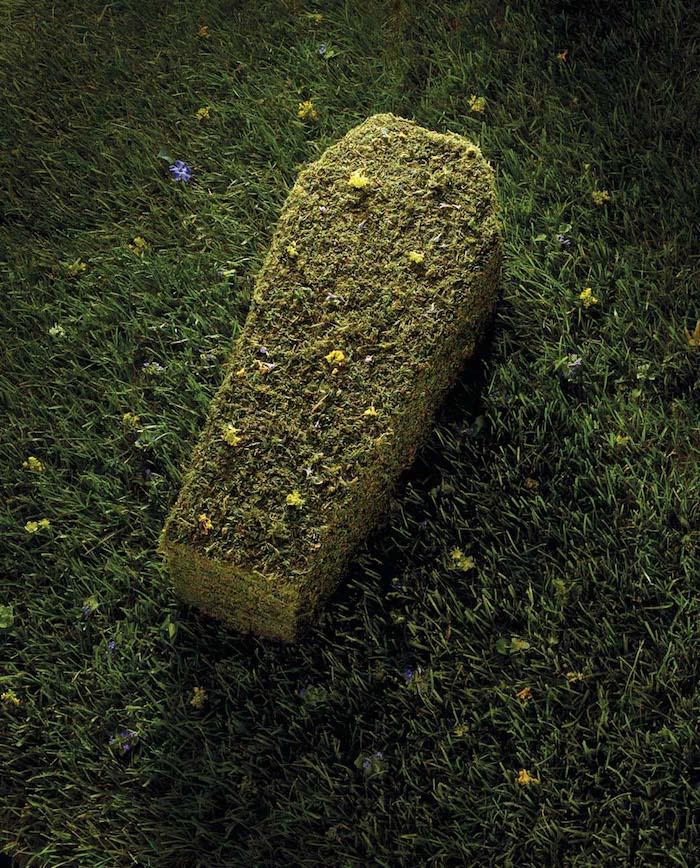

What Remains

While there are myriad ways to die, in Colorado there are only a few methods by which your body can (legally) be disposed: entombment, burial, cremation, or removal from the state. We spoke with Centennial State funeral homes and cemeteries to understand the options. Just remember: Colorado law says the written wishes of the deceased must be followed, so discuss what you want with your family ahead of time so they aren’t surprised.

Burial

Typical cost: From about $5,000 for a casket and full funeral service, plus about $5,000 for cemetery fees (plot, headstone, etc.)

What you need to know: In Colorado, a funeral home cannot move forward with a burial (or cremation or transportation across state lines) until a death certificate is on file with the county and state, which normally takes a few days. The funeral home will need information like social security numbers and the deceased’s mother’s maiden name to begin the process. Further, state law requires that if a body is not going to be buried or cremated within 24 hours, it must be either embalmed (using chemicals as a preservative) or refrigerated, so make sure your loved ones know what you prefer. Your family can opt to have your body prepared at a funeral home and then brought home for a viewing or service, though. Finally, federal law mandates that your family be given pricing details about caskets, cemetery fees, and the like before they make a decision, so they are prepared for the costs.

Cremation

Typical cost: From about $600 for transportation, refrigeration, and cremation; additional fees for urns, memorials, and/or funeral services

What you need to know: Choosing cremation does not preclude having a funeral; many people opt to have funeral services and then have the body cremated. (In this case, you’ll still need a casket, but you can rent one instead of purchasing it.) Once you’ve gone the ashes-to-ashes route, you can’t be scattered willy-nilly on federal land, in part because straight cremains are not healthy for plants. For example, your family will need to apply for a free permit—which stipulates how and where ashes can be spread—if you’d like to have your cremains placed inside Rocky Mountain National Park. The most popular national park in Colorado got more than 180 such requests last year.

Green Burial

Typical cost: From about $1,500

What you need to know: Only one Colorado cemetery (Crestone Cemetery) and handful of funeral homes (like Fort Collins’ Goes Funeral Care & Crematory) have applied for and been certified by the Green Burial Council. That doesn’t mean there aren’t various shades of “green” burial available throughout Colorado, though, at places such as Littleton’s Seven Stones Chatfield—Botanical Garden Cemetery and Lafayette’s the Natural Funeral. Among the greener ways to go: avoid embalming (so the harmful chemicals don’t seep into the ground upon decomposition); opt for a simple shroud or biodegradable casket; have your grave be dug by hand, instead of with machinery, which comes with a carbon footprint; or select a cemetery or cremation garden that uses environmentally friendlier plants for landscaping (for example, Seven Stones uses rhizomatous tall fescue for its meadow, which requires less water to maintain).

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

smelled musty, the way old cabins do, and I watched as a swath of sunlight coming through the window illuminated lazy plumes of dust. My thoughts felt as clouded and untethered as the drifting specks. I had flown in from Denver the day before and driven more than 100 miles from Phoenix to collect some of my father’s things and bring them to the hospital, where he lay in a medically induced coma.

smelled musty, the way old cabins do, and I watched as a swath of sunlight coming through the window illuminated lazy plumes of dust. My thoughts felt as clouded and untethered as the drifting specks. I had flown in from Denver the day before and driven more than 100 miles from Phoenix to collect some of my father’s things and bring them to the hospital, where he lay in a medically induced coma.