Two brothers are combining palliative care expertise, linguistics and AI to encourage more effective conversations between doctors and people receiving end-of-life care.

One afternoon in the summer of 2018, Bob Gramling dropped by the small suite that serves as his lab in the basement of the University of Vermont’s medical school. There, in a grey lounge chair, an undergrad research assistant named Brigitte Durieux was doing her summer job, earphones plugged into a laptop. Everything normal, thought Bob.

Then he saw her tears.

Bob doesn’t baulk at tears. As a palliative care doctor, he has been at thousands of bedsides and had thousands of conversations, often wrenchingly difficult ones, about dying. But in 2007, when his father was dying of Alzheimer’s, Bob was struck by his own sensitivity to every word choice of the doctors and nurses, even though he was medically trained.

“If we [doctors] are feeling that vulnerable, and we theoretically have access to all the information we would want, it was a reminder to me of how vulnerable people without those types of resources are,” he says.

He began to do research into how dying patients, family members and doctors talk in these moments about the end of treatment, pain management and imminent death. Six years later, he received over $1 million from the American Cancer Society to undertake what became the most extensive study of palliative care conversations in the US.

The resulting database contains over 12,000 minutes and 1.2 million words of conversation involving 231 patients. This is the basis of the Vermont Conversation Lab, which Bob created to analyse this data and find features of those conversations that make patients and family members feel heard and understood.

Brigitte’s job in the lab that summer was simple: listen to moments of silence and categorise them. The idea was that they could indicate emotionally charged connections between doctor and patient. Once the silences were coded, they would be used to train a machine-learning algorithm to detect them automatically – and, with them, moments of emotional connection.

You might ask what place algorithms could possibly have in this sensitive realm. The reality is that healthcare communication needs help, especially in palliative care, where practitioners seek to bring patients to their deaths as meaningfully and painlessly as possible.

In 2014, the US Institute of Medicine made improving doctor-patient communication a priority in its landmark study, ‘Dying in America’. An analogous publication in the UK, Ambitions for Palliative and End of Life Care, emphasised the need for patients, family and caregivers to have “the opportunity for honest, sensitive and well-informed conversations about dying, death and bereavement”. It reiterated that doctors need to make those conversations possible.

Most of the resulting communications training seems to offer scripts and templates to help doctors deliver bad news and make decisions with patients. But this is not enough. In this context, doctors really need to understand conversations more broadly. They need to appreciate everyone’s role in a conversation. They need to learn the ability to listen and be silent. They need to confidently recover from conversational missteps.

“Oncologists are in general very uncomfortable with this kind of thing. They want to focus on treatment, and they talk eloquently about different protocols and clinical trials,” says Wen-Ying Sylvia Chou, a programme director in the Behavioral Research Program at the US National Cancer Institute. She oversees funding on patient-doctor communication at the end of life. “But sitting in the place of being a listener is not something that clinicians are trained for or necessarily comfortable doing.”

Enter Bob Gramling. Hospitals track infection rates, bed occupancy and many other measures. Why not good conversations, too?

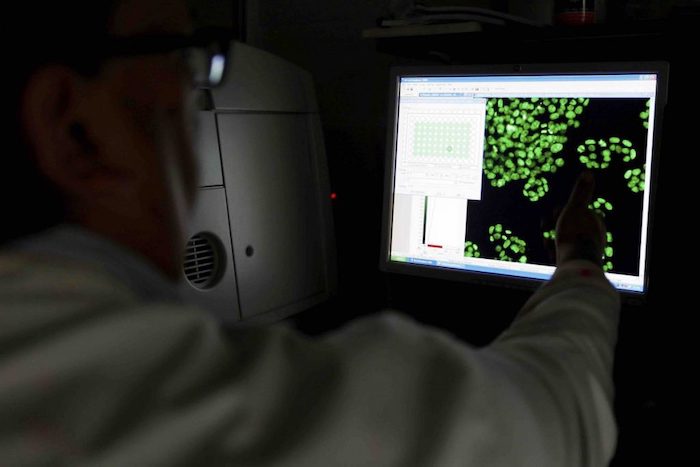

Amiable and serene, wearing a bracelet of Buddhist meditation beads, Bob sees a big role for artificial intelligence (AI) that can detect and measure the features of clinical interactions that matter to patients, then report those measurements to numbers-oriented healthcare systems.

Once such technology is widely available, he says, “we can incentivise our hospitals to build systems to improve those interactions and reward doctors for doing it”.

§

“How are you?” asks the nurse practitioner, who’s just come into the patient’s room.

“Fine,” the patient says. She’s a 55-year-old white woman with stage 4 breast cancer. Neither she nor the nurse practitioner know that she’ll be dead in five days.

“No, you’re not,” the nurse practitioner retorts.

“Oh, a loaded question,” the patient laughs.

“It’s been a long – well? No,” says her spouse.

“No,” says the patient. “It’s a polite question, it’s a polite answer.”

This is a snippet of a conversation in Bob’s database that he played to his brother David, a linguistics professor at the University of Arizona. David recognised the dynamics of this specific moment. The people in that room hadn’t been talking about care or disease, but they had been doing something important in the conversation that would affect the quality of the care.

When the Gramlings’ father died, David flew home from a literature studies fellowship in Berlin. But years earlier, he’d been intimately involved as a caregiver, witnessing a “smörgåsbord of insane, irrational communication failures” with lawyers, nurses, nutritionists and priests.

For a year after their father’s death, the brothers were swallowed by family matters. As they emerged, they began talking about palliative care communication and linguistic research in healthcare settings, and began to collaborate professionally.

The most recent result is a book, Palliative Care Conversations, published in early 2019. It aims to show physicians how conversations work, such as how clinicians and patients often understand words and phrases differently. David looked at the conversations at a granular level, using the tools of a linguistic subfield called conversation analysis. He spent years listening to audio recordings of the conversations, noting moments worth closer analysis.

Meanwhile, Bob provided clinical details about medical culture. In the last few years, he has also hung out with jazz musicians, who are master communicators when they’re improvising, and visited the Stanford Literary Lab to see how digital tools can be applied to massive literary corpuses to understand patterns too diffuse for human readers to catch.

As the Gramlings note in the book, the above back-and-forth between patient, spouse and nurse practitioner is remarkable for a first exchange between strangers. They explain that’s because “the clinician is willing to risk conventional rapport-building pathways by contradicting the family member’s self-reported state of mind”. In other words, the physician has opened the door to a looser mode of relating – and it works.

Another conversation doesn’t go as well. It’s a “pragmatic failure”, as David would say.

“When I came in,” says the nurse practitioner, “I saw you were watching Scrubs.”

“Scrubs?” the patient says. He’s a 63-year-old black man with stage 4 kidney cancer, who will live for 135 more days.

“Have you ever seen Scrubs?” asks the nurse practitioner, who is white.

“Yeah,” the patient says. “No, I wasn’t watching Scrubs.”

As the exchange unfurls, it’s clear the patient and clinician won’t connect. The clinician then seems to want to force their way to the task at hand, and forget the small talk where rapport could be built.

“When you study communication in healthcare, you’ll see a lot of monologues from doctors,” Bob says. “I don’t mean that in an insulting way – it could be really good information.” In palliative care, he explains, conversations are different: “It might be just because it’s the nature of palliative care. It’s what we do and what our value is… there is a lot of turn-taking.” That’s another term he learned from his brother. It refers to the back-and-forth of conversation.

“This is not a clean, rational, logical experience that fits on an 8-and-a-half-by-11 piece of paper, it’s a human-engaged relational endeavour,” he adds. “If we’re going to develop metrics for that, we’d better be looking at both the beauty and the science from many angles.”

Research on end-of-life communicating and decision-making typically looks at what doctors or nurses say. It rarely takes into account the deeper linguistic and cognitive factors that influence patients’ abilities to communicate in the first place.

One study, by speech-language pathologists in the late 1990s, showed just how large these language challenges can be. They gave a battery of language comprehension and memory tests to 12 hospice patients: 11 of them couldn’t recall words, had difficulty understanding things and pronouncing words, and had difficulty remembering what was said to them. These symptoms get in the way of normal activities, like having conversations.

Even something as crucial as how well older patients can hear gets overlooked. In a 2016 survey of 510 hospice and palliative care providers across the US, 87% of them said they did not screen for hearing loss, even though 91% of them agreed that patients’ hearing loss impedes conversation and negatively affects the quality of the care they receive. Only 61% said they felt confident nonetheless that they could deal with patients with hearing problems.

The Gramlings pay a remarkable amount of attention to another factor: the pain, shortness of breath, fatigue and medications that can keep patients from communicating normally.

In his research, David has addressed what he calls “language in extremis”: what happens when people’s ideas about language and communication buckle under the strain of circumstances, as in multilingual experiences in Nazi concentration camps, or interpreting in border patrol detention facilities.

End-of-life medical conversations also often involve language in extremis. As cancer brings a person’s life near to its end, they may have lost some of their lifelong communicative powers to the disease or its treatments. They may have less ability to speak subtly and indirectly, which is important for politeness. Shallow breathing shortens utterances, and drugs may block word-finding. All of this reinforces an asymmetry in communication that doctors don’t always grasp.

A physician might encourage a patient to speak openly, and indicate their willingness to listen, but in practical terms, “That gesture doesn’t quite work,” David says, and doctors need to understand why.

At the same time, people still hew to lifelong social conventions about being a user of their language. They might be dying, but “They don’t back away from their interactional responsibilities,” David says. They honour turn-taking; they don’t interrupt. They tell jokes, they use family language, and they create mini-rituals of inclusion and exclusion, often to deal with the communication asymmetries.

“If I were picturing the developmental arc,” says David, “it wouldn’t be coasting down into death. It would be all the way and sometimes heightened. The kind of complex literacy you need to use in a hospital setting in a serious illness, and managing all your oncological terms – it’s almost like the competencies themselves get expanded in this end of life.”

§

In his lab, Bob is examining even more fleeting aspects of conversations, such as pauses. It’s an interesting choice, because pauses might be considered as a sign that a speaker has lost their way or that an interaction is breaking down. On the other hand, pauses are easy to locate in the acoustic signals of recorded conversations. And they might indicate where someone is listening or about to say something important, so they might be a good thing.

Bob’s team used machine learning to identify pauses of 2 seconds or longer in spoken conversations, then human coders like Brigitte Durieux tried to categorise them, looking for ones that were more than just silence.

Because they didn’t have access to what the doctors or patients were actually thinking, they looked for the presence of emotional words and other sounds like sighs or crying on either side of the pause. Did a question about the quality of life, treatment hopes, prognosis or dying precede the pause? If so, the pause may have been because the doctor invited the patient to consider something.

The team found that during some of these pauses, some connection, shift or transformation was occurring. These “connectional silences” were rare. Out of a set of 1,000 clips with pauses, a mere 32 were connectional in nature. They were brief, as well, most lasting less than four seconds. But there’s still power in them.

The dynamics of a conversation change dramatically after such a connectional silence. Suddenly, a patient will be talking more than they did earlier. They’ll be directing the conversation, not the doctor. It’s as if the mutual agreement to pause for two seconds spilled into an agreement to shift roles.

“No, for some reason I guess I just in my head was gonna be on [chemotherapy] for the rest of my life and everything was gonna be hunky dory and…” a patient begins.

A 2.9-second connectional silence follows. The doctor inhales audibly, to signal they will respond, which makes the patient pick back up.

“You know. I knew early on, I mean you told me early on it’s not like and then this will be the rest of my life. Something, you know, might go down.”

The doctor responds. “Something. That can be a very hard thing to think about. That here we found something that’s helping but you can’t stay on it for the rest of your life.”

In other moments, the silence comes after a doctor has said something empathetic.

“It’s rare of me to tell somebody point-blank you’ve got to stop. However, I will say you have my permission to set limits,” the doctor says.

“Okay,” says the patient, then falls silent for nearly seven seconds.

His wife chuckles. “He can’t stand the thought of it. I can tell by his laugh,” then she laughs.

“I know he can’t stand the thought of it,” the doctor says.

“No, that’s okay,” the patient says. “I’ll get used to it.”

Or in another instance, the doctor tells a patient’s spouse, “what you feel is really hard. It’s really hard.” There’s a 2.8-second silence.

“I just wish he had a better quality of life.”

“I know, I know,” says the doctor.

Even though these connectional silences don’t happen often, Bob thinks they’re good linguistic markers of connection exactly because doctors don’t commonly use them. When someone good at monologuing and interrupting falls silent, it may mean they’re allowing something else to happen.

Bob surmises, “More often than not, the conversations that have a lot of space in them are probably going to lead to people feeling more heard and understood.”

§

Judy had a question. Having come to the hospital at the University of Vermont to recover from the flu, this elegant, 83-year-old woman was lying in her bed. Two doctors had come to her room bearing news. It was cancer, not the flu, and it had spread from her liver. She could undertake a course of chemo, or she could have her pain managed as she died.

She turned to her daughter, Kate, sitting beside her. “What should I do?” she asked.

When the doctors had requested this meeting, Kate had dropped everything to be there. It seemed unusually serious. Now she knew why. She wondered why she hadn’t seen the signs of her mother’s cancer. Judy’s skin had started to look yellow, she recalled. But instead of recommending a check-up, she bought her mother some pinker make-up.

In this pivotal conversation, the doctors presented the options but also wanted to know what was important to Judy. They knitted the science together with thoughtfulness and compassion. Kate was struck by their slow, almost languid approach to delivering the news.

Slowly it dawned on her that this was a conversation about her mother’s death. Neither of them had prepared for this. Not now, not so soon.

“It had the nature of a conversation with a clergyperson rather than a doctor,” she remembers. Pastoral kept coming to mind.

At the end of the conversation, one of the doctors gave her his card. It was Bob Gramling. Kate has since seen the bright blue spectrographs showing gaps in conversation – where the pauses occur. She thinks these are important moments as well.

“Where there’s silence, where there are gaps, that’s where the caring shows up,” she says. “I think it’s incredible work to point out to doctors there’s a lot going on in the silences.”

Bob and David have only scratched the surface of how these conversations work. So far they have only studied English speakers, for example; pauses work differently in other cultures, so they need data on those moments, too. And because their data comes from people with cancer, there’s a concern that the analysis may be skewed.

With cancer, says Wen-Ying Sylvia Chou of the National Cancer Institute, most patients have time: “They continue to be themselves and continue to be part of the conversation and any ongoing discussion.” With other diseases, though, there could be more risk that the person would “lose cognitive function or physical function”. In those cases, she says, conversations “would look very different”.

Healthcare’s use of natural language processing – technologies that treat language as data – is expanding, and the chances are good that research like that of the Gramlings will expand to cover conversations with people who have other serious illnesses.

Bob isn’t the only researcher exploring the use of artificial intelligence in palliative care. In 2017, James Tulsky, a palliative care physician at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston and a Harvard professor who studies health communication, stressed that “mass-scale, high-quality automated coding will be required” to give feedback that helps clinicians improve their expressions of empathy.

Tulsky turned to Panayiotis Georgiou, a computer engineer at the University of Southern California, to develop automated detection of emotional connections between doctors and patients. In 2017, a team headed by Georgiou showed that certain acoustic features of the speech of couples in counselling could be used to predict marital outcomes. What if algorithms could do the same for palliative care conversations?

“The technology in theory exists out there to do all this,” Tulsky says. “It’s just a matter of doing enough research, running enough iterative trials, training up the machines to actually get these algorithms trained well enough so you could apply them to more random talk.”

I ask Judy’s daughter Kate what she thinks of using artificial intelligence to enrich human connections. “I wouldn’t worry about the technology,” she says. “The more technology, the more sacred the conversation becomes.”

What does she mean? Anything that enables humans to use their voices more effectively with each other is a good thing, she explains: “It’s because of the increasing technology that the interaction becomes more wonderful.”

§

What is a conversation? It’s a setting where humans interact, often for a purpose but sometimes for none at all. People have to learn how to have conversations but when they become expert in their culture’s conventions, conversing becomes so automatic it feels natural.

Modern healthcare has hijacked conversation and made it a tool by which physicians can achieve their ends.

According to David, “The contemporary hospital still understands ‘conversation’ as ‘making a pre-determined X happen through conversation’.” This is a barrier in serious illness and end-of-life care, where the conversations need to be venues for figuring out what the X might be.

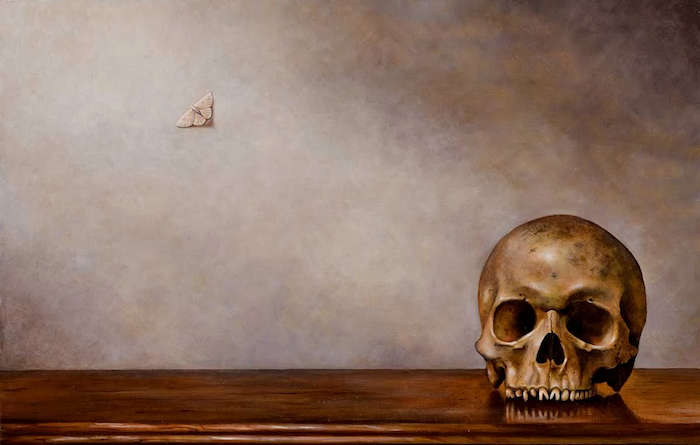

At the end of a patient’s life, there may not be effective medical treatments, just things to discuss and plans to make. This may need a more natural conversation than a medical one, a conversation in which none of the participants may know what the outcome will be.

After all, these conversations aren’t just for doctors; they’re for patients, too. And family members, nursing aides, housekeeping staff. “There are a lot of human beings who have a vested interest in this other human,” Bob says.

There are critics who don’t think artificial intelligence and machine learning have a role to play in palliative care. Bob’s view is that shying away from analysing this kind of conversation in this way means that essential opportunities for improving it will be missed.

“It is helpful, as a discipline that has historically thought of communication as just the art of medicine, to actually think that, no, this is a science,” he says. And understanding that science could help us re-engineer the healthcare system to support more meaningful conversations.

He’s aware of the delicacy in institutionalising and commodifying a human interaction, though. “As a physician,” he says, “I was afraid of being a researcher that was going to oversimplify this kind of sacred experience into something that’s measurable and convenient and essentially meaningless.”

That’s where Brigitte Durieux struggled with her feelings as she listened to thousands of audio clips of pauses. In some conversations, people were laughing, but she was struck by the loneliness in others. She had begun to recognise patients’ voices and wondered what had happened to them.

“Nobody is perfect, but there are times when one realises there’s something that could be said to make this feel less like a loss,” she says. Sometimes she whispered under her breath something the doctors could have offered instead.

After Bob found Brigitte crying, he wrote an ethics proposal to the hospital so that he could introduce a new procedure into his lab. He borrowed an idea from the hospital’s palliative care unit, where staff gather every week to say the names of people who have died, then ring a singing bowl.

Now, at the start of every Vermont Conversation Lab meeting, a researcher reads the name of one of the patients from the database and rings the bowl. So far, they have gone through the list of names twice.

The ceremony helps, says Brigitte, because it reduces the guilt of turning a sensitive moment in someone’s life into a piece of data.

“What it does ultimately,” she says, “is recognise the humanity of things.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!