Award-winning Australian writer Cory Taylor spent the last years of her life fascinated with her own mortality, writing a memoir that she hoped would trigger more open and honest conversations about death. In her last weeks, she shared some of her insights in a bedside interview with Richard Fidler.

Cory Taylor died on Tuesday, without pain, and with her family all around her. She had just turned 61.

For a decade, she had lived with the certainty of her death from melanoma-related brain cancer.

Her final project, Dying: A Memoir, was written earlier this year in the space of just a few weeks.

Julian Barnes wrote after he read Dying, ‘We should all hope for as vivid a looking-back, and as cogent a looking-forward, when we reach the end ourselves.’

Her publisher, Michael Heyward, announced plans to publish the book around the world in the coming months.

Cory’s writing career started with screenwriting, moved into children’s books, and then novels for adults.

Her first novel, Me and Mr Booker, won the Commonwealth Writers Prize (Pacific Region) and her second, My Beautiful Enemy, was shortlisted for the Miles Franklin Literary Award.

Just three weeks ago, Richard Fidler spoke to Cory at her home in Brisbane. Here are some highlights of their conversation about her life, and her feelings about her own death.

On life in her last weeks

‘I move from my bed in my bedroom, to my sofa here in the living room, and basically I stay here and I’m fed delectables all day and that’s about it.

‘Reading, I find pretty exhausting, which is sad. Even watching stuff on TV taxes you a lot. But I miss reading, so I do force myself to read.

‘One of the things I do is dream a lot about life. Not dream as in sleep dreaming, but day dreaming. It’s not as if I’m gathering memories but I still am very steeped in memory.

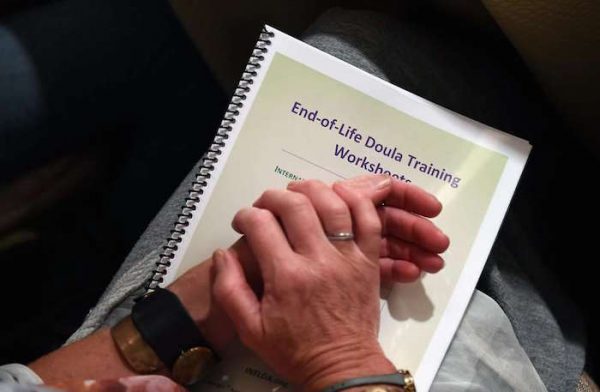

On being a ‘beginner’ at dying

‘I’ve never seen anybody die, so it’s not something I know anything about.

‘I think we should all study it. I think we should all spend time with people when they’re dying.

‘Basically, it’s all hidden from us … we’re so ignorant about how does it happen actually, physically, and then what do we read from that?

‘I wish I’d known a lot more about it before now.’

On the idea of assisted dying

‘I’ve always felt that I have controlled my destiny, pretty much. That may be a compete delusion—well, obviously it is, because I’m dying and I didn’t plan that.

‘But it’s the lack of control when you’re dying that is so terrifying.

‘Even to think that you have the possibility to control the circumstances, to put yourself out of your own misery, it just renews that sense you do have some control over what’s going to happen to you.

‘And that is a real comfort.’

On whether to think about dying

‘I don’t think you should think daily on it, but I do think it’s worth having in the back of your mind, in terms of the kinds of conversations you want to have with your family … so that they have a sense that you are not there forever.

‘That means that you value certain things now and you want to enjoy certain things now and there are a whole lot of things you don’t want to do and you don’t want to waste time on, because you’re aware that it’s all finite and it can be over faster than you think.’

On cancer

‘The last thing I wanted was to write a morbid analysis of my cancer treatment or my “battle” with this disease.

‘The war metaphor doesn’t really work for me at all. It is a “coming into” dying, as if that’s a natural flourishing in a way.

‘It is a momentous thing. It’s the most important thing that’s going to happen to you after your birth.

‘The complete randomness of the whole thing … that’s not what saddens me about dying. The ultimate randomness is death, isn’t it?

‘Despite all the randomness and precariousness of it all, it’s still an enormous gift and an enormous blessing, so why would you begrudge any of it? It doesn’t really matter in the end.’

On consoling loved ones

‘People have been to me surprisingly emotional about me dying, when I don’t feel as sad as they are. You want to protect them from that and say: “It is alright.”

‘I think my book has helped my friends to realise I am telling the truth. I am OK.

‘I have managed to do the things I wanted to do, and I’m not going out full of regrets or grudges, or anything like that.’

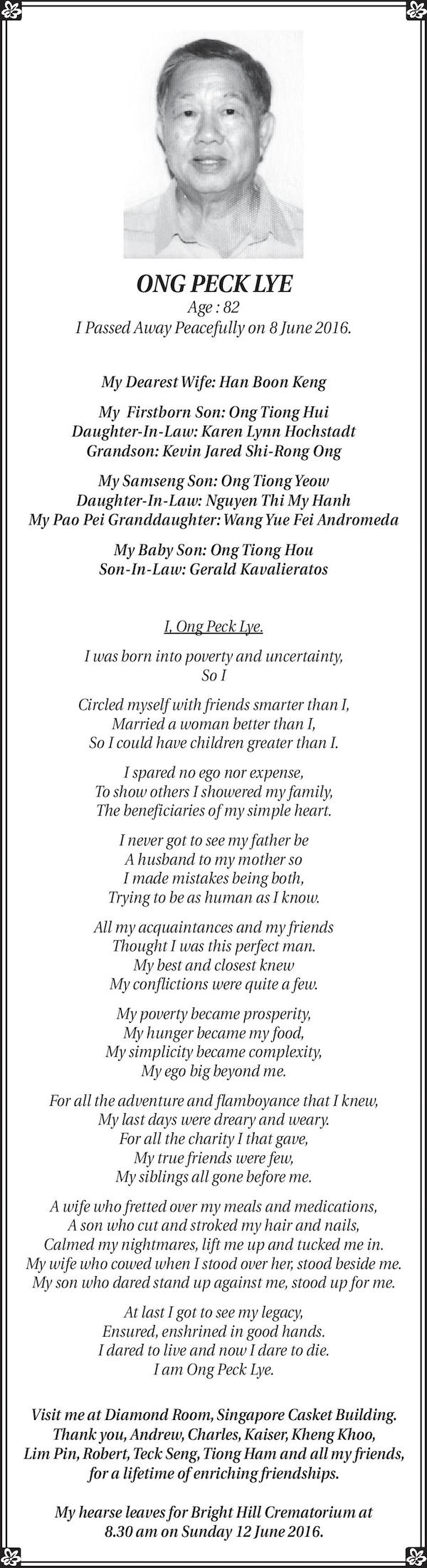

On her funeral plans

‘I’m a bit hazy on my funeral plans. I had a book launch (in Brisbane) and I was just there in the ether, talking on Skype. And I could see the audience, and it was a bit riotous, and there was lots of laughter, and lots of tears.

‘A lot of people who went called me later and said, “Oh Cory it was fabulous, it was like being at your funeral.”

‘I thought, “Oh that’s good. I’ve done it now. I don’t have to do it again!”

‘So I’d probably want a repeat of the launch, which is just a room full of friends, and lots of grog and food, and people saying lovely things about you. That’d do.’

Complete Article HERE!