Barry Hyman always swore he’d die peacefully on his own terms. But living in a faith-based nursing home put his family in a difficult position to help him

By Kelly Grant

[O]n the night that 83-year-old Barry Hyman was to receive a doctor-assisted death, his daughters were on edge, petrified that at any moment someone would burst through the door and stop them from granting their father his final wish.

Enfeebled by a stroke and diagnosed with lung cancer, Mr. Hyman had asked to die at home.

But his home at the time was a publicly funded Jewish nursing home in Vancouver whose board forbade assisted deaths on site, saying the newly legal practice violated the values and traditions of the Jewish faith.

That left Lola Hyman, the younger of Mr. Hyman’s two daughters and his main caregiver, with a choice.

She could transfer her father to an unfamiliar clinic to die, or she could sneak Ellen Wiebe, one of the country’s leading doctor-advocates of assisted dying, into her father’s room to help him die in his own bed.

Lola and the rest of her immediate family settled on the latter. They would deal with the fallout later.

Their first priority was making sure that Mr. Hyman died peacefully on his own terms, as he’d always sworn he would.

“The room was very quiet. We just held his hand and stared at him,” Lola said. “My sister was sobbing, just sobbing. I was a stone. A complete stone. My heart was racing that someone would open the door.”

nstead of focusing on their goodbyes, the Hyman family spent the last moments of Barry’s life worrying that they would be discovered and prevented from completing a legal medical procedure inside a publicly funded care facility.

Their story is an extreme example of the choices that grievously ill Canadians still face – 18 months after Ottawa’s assisted-dying law took effect – if they wind up near the end of their lives in a hospital or nursing home that refuses to allow assisted dying, either for religious reasons, or because the facility has simply decided to say no.

It is not clear if these institutions enjoy the same Charter-protected religious freedoms as individuals when it comes to refusing assisted deaths because the issue has not yet been tested in court.

In the vast majority of cases, such patients are transferred to another facility to die. But it isn’t always easy to find a place to send them.

Sometimes overcrowded secular hospitals say no. Sometimes the only hospital or nursing home in town is faith-based.

Other times, an unconventional location has to suffice: In Vancouver, Dr. Wiebe has opened her women’s health clinic after-hours for 34 assisted deaths, which means that in some cases, Catholic health-care facilities have transferred patients to an abortion clinic to die.

Canada’s religious health-care organizations, which have been tending to the sick in this country since long before Medicare, say they are doing their best to support terminally ill patients without betraying their own faith, offering options like palliative sedation to make patients’ natural deaths as painless as possible.

Some have softened their objections to the early parts of the medical-aid-in-dying process, allowing outside doctors to come in and conduct eligibility assessments on patients who are too fragile to be transferred for an appointment.

But when it comes to actual physician-assisted deaths, religious facilities – be they Jewish, Baptist, Catholic or otherwise – are refusing to allow the practice on their grounds.

“The core issue … is that Catholic and faith-based organizations are committed to the inherent dignity of every human life and would never intentionally hasten the end of a life,” said Christopher De Bono, vice-president of mission, ethics, spirituality and indigenous wellness at Providence Health Care, a Catholic health-care network that includes St. Paul’s Hospital in downtown Vancouver.

Nobody on either side of Canada’s assisted-dying divide is arguing that individual doctors or nurses should have to participate in assisted dying if they object to it, said Shanaaz Gokool, the chief executive officer of the advocacy group Dying with Dignity Canada.

But she is incensed that every province with faith-based health-care organizations except Quebec has allowed taxpayer-funded hospitals and nursing homes to refuse requests for a procedure the Supreme Court of Canada has declared a Charter-protected right. (And even Quebec allows some hospices to opt out.)

“Why are we making this so hard for people when it’s the one medical treatment that you have a legal right to in this country?” she said.

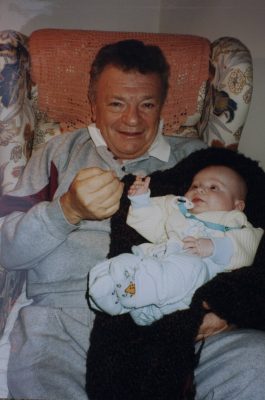

Throughout Barry Hyman’s long and colourful life – through founding a small publishing company, raising two daughters, divorcing twice, studying history and English literature at Simon Fraser University as a senior citizen and logging countless hours at casino poker tables – he told anyone who would listen that he had no desire to linger if his health failed.

“Ever since I can remember, and I mean over 50 years, my father has always told me that if he ever got to the point that he no longer had the ability to comprehend, the ability to socialize, the ability to do the things that he wanted to do … he was done,” said Leah Hyman, 54, Mr. Hyman’s eldest daughter.

Mr. Hyman, a Winnipeg-born businessman, dreaded one day losing the vitality that infused his life, first as a young waiter on the railroad, then as the founder of an Edmonton printing company that churned out small Jewish newspapers and government directories.

He also owned pool halls, nightclubs and a roller rink. He was still on J-date, the online Jewish matchmaking service, in his 80s.

“He just rolled up his sleeves and dove into everything,” Lola said – including introducing his only grandson, Jackson Doyle-Hyman, now 19, to the worlds of business and (responsible) gambling.

Mr. Hyman once took a kindergarten-aged Jackson to the track and showed him how to bet $10 at a time on the top horses.

Lola, now 51, later found cash spilling out of the pockets of Jackson’s little navy polo jacket.

As he grew older, Jackson often tagged along to business meetings where ad space was traded for car parts or hotel stays, a practice called “contra.”

“We always joked that he could have built a Ferrari with all the car parts he got contra for,” Jackson said.

Mr. Hyman was already a diabetic with congestive heart failure when he was diagnosed with lung cancer early in 2016.

But his health didn’t really begin to deteriorate until an ill-fated trip to a tanning salon to treat his psoriasis.

The tanning bed left Mr. Hyman with a burn on his left foot no bigger than a quarter. The wound festered for nearly a year, despite every effort to heal it.

By October of 2016, doctors were talking about amputating his leg. Mr. Hyman instead chose to undergo a procedure in which surgeons bypassed a clogged leg artery that was keeping his foot from healing.

Ten days later he had a stroke, a known risk of the operation.

His mind was still sharp, but the stroke impaired his speech – a devastating blow for a man who adored the English language and insisted upon its correct use.

“This was a guy who read two papers a day and did the New York Times crossword,” Lola said, “And he no longer could do any of that.”

It was clear to Lola that her father could not keep living in his own apartment, as he had before the stroke.

The family’s first choice was the Louis Brier Home and Hospital, Vancouver’s only Jewish nursing home. But it was full.

Reluctantly, Mr. Hyman accepted a spot at St. Vincent’s: Brock Fahrni, a Catholic home where he shared a room with three other men.

Mr. Hyman and his family made a preliminary inquiry about assisted death with a doctor there, but it went nowhere.

When, in April of 2017, a bed in a private room became available at the Louis Brier Home, Lola leaped at the chance.

She knew that, like the Catholic home her father would be leaving, the Louis Brier did not permit assisted deaths on site.

She hoped that moving her father to a nicer place where he could live among his Jewish peers and Jewish culture would persuade him to abandon his talk of assisted death.

But Mr. Hyman wouldn’t let go of the idea. Although Lola didn’t want to lose her father, she was willing to help him fulfill his final wish.

On April 26, a week after moving to the Louis Brier, Mr. Hyman and Lola met Dr. Wiebe at her office.

A few hours later, Dr. Wiebe e-mailed Lola to say her father’s constellation of health problems made him eligible for an assisted death.

When the Supreme Court of Canada struck down the Criminal Code prohibition on physician-assisted dying in February of 2015, the judgment made it clear that invalidating the law would not compel doctors to help their patients die.

The court was silent, however, on whether entire health-care organizations could bow out of medical aid in dying.

Parliament passed a law that was silent on the question, too, even though a special joint committee of the House and Senate had recommended that Ottawa work with the provinces to ensure all publicly funded health-care facilities provide medical assistance in dying.

Jay Aubrey, a lawyer with the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association, the group that helped topple the ban on assisted dying, predicted that a legal challenge against an objecting religious health-care facility such as the Louis Brier Home would be straightforward.

The home is 67-per-cent publicly funded and is therefore “acting in the shoes of government,” she said. “That’s why they’re bound by the Constitution.”

Ms. Aubrey sent a letter to the Louis Brier Home last May making that case on Mr. Hyman’s behalf.

But Richard Moon, a University of Windsor law professor and an expert in religious-freedom cases, said past precedents suggest public funding alone is not enough to saddle a third-party like a nursing-home operator with the constitutional duties of a government.

On the contrary, he said, religious health-care organizations could try – and might succeed, under the right circumstances – to claim they are entitled to the same Charter-protected religious freedoms as individuals, allowing them to rebuff government orders that breach their beliefs.

Prof. Moon said there could be a simple way around that: Provincial governments could withhold funding from health-care organizations that do not allow assisted dying, so long as they applied the rule without discrimination.

“It’s a matter of nerve here, isn’t it?” he said. “Is the government really willing to withdraw funding from these organizations? Are these organizations really willing to risk the loss of funding?”

So far, everywhere outside Quebec, the answer is no.

Grievously ill patients are instead being transferred out of non-participating institutions in numbers that are difficult to determine at a national level.

British Columbia’s five regional health authorities together logged a total of 61 transfers as of the beginning of December. Alberta has recorded 42; Saskatchewan is aware of at least 11; Manitoba has recorded eight.

The Maritime provinces say they are either not aware of any such transfers or are not tracking them.

The outlier is Ontario. Not only has Kathleen Wynne’s government declined to track transfers, it passed a law exempting hospitals, nursing homes and hospices from freedom-of-information requests about medical aid in dying, a move the province’s privacy commissioner denounced.

The blackout, which a spokesman for Ontario’s Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care said was enacted to protect health-care workers and institutions that provide assisted dying, makes it impossible to say how many hospitals in Canada’s most populous province are refusing to allow the practice.

But ministry officials have hazarded a guess: As many as 27 publicly funded Ontario hospitals – one out of every five in the province – would “potentially object to [medical aid in dying] based on their stated religious/ideological values,” according to an internal briefing note that Dying with Dignity obtained through a freedom-of-information request.

“There are 7 cities/towns in Ontario with potentially objecting hospitals that have no alternative hospitals within 100 km. Moreover, there are 4 other cities/towns with only one neutral hospital for the whole region.”

In Vancouver, when patients are looking for an alternative location to receive an assisted death, one option is Dr. Wiebe’s Willow Women’s Clinic on the 10th floor of a downtown high-rise.

The space has much to recommend it, according to Dr. Wiebe: wheelchair access, a separate waiting room for family and, in the larger of the two rooms she reconfigures for assisted deaths, a spectacular view of the mountains.

Still, there’s a makeshift feel to the arrangement. Patients take their last breaths on a bedsheet-draped patio recliner, the same piece of furniture on which the clinic’s regular clients recover after having an intrauterine device inserted.

In one “dreadful” case, a man who wanted to die without his family present was transferred from a Catholic facility and mistakenly left outside by a medical transportation service, next to the pounding of jackhammers, Dr. Wiebe said.

“We need to get to [the government] and say, ‘This is completely unreasonable – you can change it with the stroke of a pen,'” Dr. Wiebe said of the B.C. NDP’s decision to continue allowing publicly funded faith-based institutions to opt out of assisted dying.

B.C. Health Minister Adrian Dix declined an interview request for this story.

A spokeswoman for the Ministry of Health emphasized that all of the regional health authorities in B.C. have care co-ordination services that help smooth the transition for patients who have to move from one place to another for an assisted death.

She said the provincial government has “no plans to terminate” a long-standing agreement that allows members of a group called the Denominational Health Association (DHA) to refuse to provide services that are inconsistent with their religious values.

The DHA represents 44 health-care facilities in B.C., including the Louis Brier Home, where Barry Hyman wanted to die.

The entrance to the Jewish faith-based Louis Brier Home and Hospital in Vancouver.

A few weeks after meeting Dr. Wiebe, Lola Hyman e-mailed David Keselman, the chief executive officer of the Louis Brier Home, to formally ask that her father be allowed to die on site, despite the home’s policy.

Mr. Keselman sent his formal reply to Lola on May 25. “Quite some time ago,” he wrote, “the governing board, along with the leadership of Louis Brier, decided that Louis Brier will provide care and services to the residents according to the Orthodox Jewish stream.”

The home was willing to allow eligibility assessments, he continued, but not assisted death itself.

“Lola I realize that this may not be what you would have liked or have wanted to hear,” Mr. Keselman wrote. “If so I regret this.”

For weeks afterward, Lola weighed her options. She didn’t like the idea of sending her father to die at Dr. Wiebe’s office or an unfamiliar seniors’ home suggested by the care co-ordination service at Vancouver Coastal Health.

“The thought of doing my father’s provision in a clinical setting [with a bed] that looked like a dentist’s chair was so unsettling for me,” she said. “I didn’t share it with my father. I did not burden him with any of the logistics. I just said, ‘When you want it to happen, Dad, it will happen.'”

Mr. Hyman ultimately decided to die on June 29.

Leah and her wife, Tori, drove up from their home in Oregon that day to be with Lola and Jackson in Mr. Hyman’s room.

Early in the evening, Lola went to the front door of the nursing home to welcome Dr. Wiebe and a nurse as though they were old friends paying a visit.

They hid their medical equipment and lethal drugs in oversized bags.

Dr. Wiebe, her nurse and Lola went in to Mr. Hyman’s room and shut the door. Leah, Tori and Jackson stood guard outside.

When a nurse from the home came by to try to give Mr. Hyman his regular medications, Leah offered to deliver the pills, shooing the nurse away with a forced joke or two as though she were not minutes away from watching her father die.

“It was rough,” she recalled, crying. “I was not the best daughter. We just didn’t communicate well. We loved each other and we knew each other and we were there for each other. But this was the one thing I was going to make sure that we did, that we followed through on. He was going to go the way that he wanted to go.”

When Dr. Wiebe was ready to begin injecting the medications, Leah, Tori and Jackson came in and joined Lola at Mr. Hyman’s bedside.

He died peacefully in about 10 minutes that felt much longer to his family. “I’ll never forget looking at the door all the time,” Leah said, “terrified that someone was going to come in.”

In the end, nobody interrupted Mr. Hyman’s death. Dr. Wiebe filled out the death certificate, gave it to Lola, and left.

About 20 minutes later, Lola approached the home’s nursing station and did something she instantly regretted: She told them her father had died, but didn’t say how.

“I was frozen,” she said. “If I could go back, I would have walked up to that nursing station and said, ‘Dad passed of [medical aid in dying],’ but I can’t imagine what I would have been bombarded with as Dr. Wiebe was getting into her car.”

The next morning, after Dr. Wiebe reported the details of the case to Vancouver Coastal Health, Lola sent the Louis Brier Home a copy of Mr. Hyman’s death certificate.

The aftermath of Mr. Hyman’s death was hard on the home’s staff, especially the front-line workers who were initially puzzled by his unexpected death, Mr. Keselman said.

“We had no opportunity to communicate with the staff, to prepare them, to explain anything,” he said. “It was very traumatic.”

Mark Rozenberg, the chair of the ethics committee of Louis Brier’s board, emphasized that the home makes no secret of its opposition to assisted dying.

“Anyone who comes here knows what our policy is,” he said. “And if they don’t like the policy, they should go somewhere else.”

The home has since filed a formal complaint against Dr. Wiebe with the College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia, the regulator for doctors in the province.

The complaint does not faze Dr. Wiebe; she is confident the college will see she was fulfilling her patient’s wish to die at home. (A college spokeswoman declined to comment.)

But Lola is heartsick at the thought of Dr. Wiebe in trouble, just as she is heartsick about having upset the front-line staff at Louis Brier.

None of this – including the stress her family experienced on the evening of Mr. Hyman’s death – would have happened if the government compelled all publicly funded health-care facilities to allow assisted dying, Lola said.

“Everyone is entitled to their religious beliefs and traditions and customs,” she said. “But when it comes to somebody who is very sick and dying, we need to have a different approach.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!