By Barbara Kate Repa

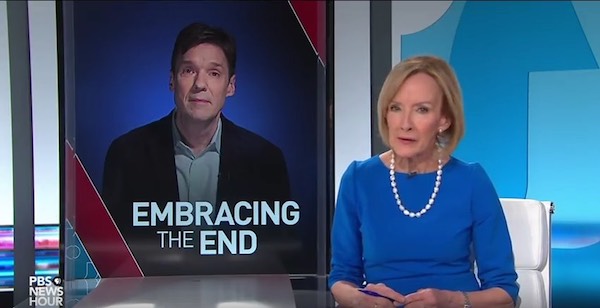

[T]hese days, everyone from poets to professors, priests, and everyday folks all opine about what makes a “good death.” In truth, deaths are nearly as unique as the lives that came before them — shaped by the combination of attitudes, physical conditions, medical treatments and people involved.

“A good death can, and should, mean different things to different people,” says Haider Warraich, MD, author of “Modern Death – How Medicine Changed the End of Life.” “To me, it means achieving an end that one would have wanted, and that can really mean anything – from being in the intensive care unit, getting all sorts of life-sustaining therapies, to being at home, surrounded by family, getting hospice care.”

Still, many have pointed to a few common factors that can help a death seem good — and even inspiring — as opposed to frightening, sad, or tortuous. By most standards, a good death is one in which a person dies on his own terms, relatively free from pain, in a supported and dignified setting.

“I think what makes a good death is really different for every individual, but there are some common threads that occur with each person I’ve seen,” says Michelle Wulfestieg, executive director of the Southern California Hospice Foundation (SCHF) and author of “All We Have is Today: A Story of Discovering Purpose.”

Some of patients’ most common end-of-life priorities include being at peace spiritually, knowing that they have the support of loved ones, having their affairs in order and being reassured that they won’t have a painful death, says Wulfestieg, who has worked in hospice care for 14 years.

Having affairs in order

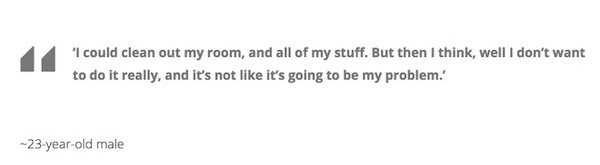

Not everyone has the luxury of planning for death. But those who take the time and make the effort to think about their death in advance and plan for some of the details of their final care and comfort are more apt to retain some control and say-so in their final months, weeks and days.

Legal specifics of such planning can include taking steps to get affairs in order by:

For those considering hospice care at the end of life, another crucial end-of-life planning step is to elect the hospice benefit under Medicare, notes Joseph Shega, MD, national medical director for national hospice care provider VITAS Healthcare. He points out that hospice care is covered by Medicare, along with most health insurance providers.

Richard Averbuch, Executive Director of the Massachusetts Coalition for Serious Illness Care, cautions not to wait until a serious illness or crisis before planning for end-of-life care.

“The best time to name a proxy and talk about your preferences is now – whatever your stage of life. Think of it as part of your overall wellness program – just as important as preventive care, an exercise regime, and a good diet,” he says. “And you need to revisit the conversations periodically, since your feelings may change as you age or as your health status changes.”

Controlling pain and discomfort

Most Americans say they would prefer to die at home, according to recent polls. Yet the reality is that some three-quarters of the population dies in some sort of medical institution, many of them after spending time in an intensive care unit.

Part of that may be due to misunderstandings about the different options for treating a patient’s pain in their final days.

“There are still people who are uncomfortable with the use of pain medications at the end of life, even as their use is essential for the patients who are in pain,” says Warraich.

As life expectancies increase, more people are becoming proactive. A growing number of aging patients are choosing not to have life-prolonging treatments that might ultimately increase pain and suffering — such as invasive surgery or dialysis — and deciding instead to have comfort or palliative care through hospice in their final days.

Ways to help ensure a “good death” on an emotional level

Along with the practical matters of having one’s affairs in order, it’s equally important to prepare for death emotionally, to spend time with loving people toward the end of life, and to have spiritual sustenance.

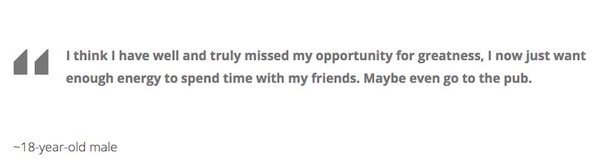

Having few regrets

“Patients really want to know that their life had purpose, that they made a difference and that their lives mattered,” says Wulfestieg. “It has to do with family a lot of times, saying those I love yous and goodbyes.” The SCHF often works to reunite dying patients with family members,

including those who have long been estranged.

Often quoted among hospice care providers and in the literature on death and dying are the tenets in “The Four Things That Matter Most“, by Ira Byock, a medical doctor who professes the need for a dying person to express four thoughts at the end of life:

- I love you.

- Thank you.

- I forgive you.

- Forgive me.

At the time Caring.com spoke with Wulfestieg, her organization was preparing to reunite Marilyn, a woman with ovarian cancer and only a few weeks to live, with her three estranged adult children and grandchildren.

Due to Marilyn’s problems with drugs, alcohol and crime, all three of her children grew up in foster care, and she’d lost contact with them. Her dying wish was to have a family meal with her children and grandchildren, so SCHF have arranged to fly out Marilyn’s family members to make it happen, Wulfestieg says.

“That’s really her dying wish, to be able to say ‘I’m sorry, I love you and goodbye,’” she says. “It’s really a story of grace and forgiveness and hope.”

Receiving mindful care and support

The right company can help aid a “good death.” Although dying may be scary or sad or simply unfamiliar to those who are witnessing it, studies of terminally ill patients underscore one common desire: to be treated as live human beings until the moment they die.

Most also say they don’t want to be alone during their final days and moments. This means that caregivers should find out what kind of medical care the dying person wants administered or withheld and be sure that the medical personnel on duty are fitting in skill and temperament.

“Before health care decisions around end-of-life care can be delineated, clinicians and patients must first recognize when life-limiting conditions such as heart failure, lung disease or cancer are no longer responding to disease-modifying treatment,” Shega says. Next, he says, there should be “a conversation between the patient and clinician about end-of-life care and the role of hospice.” He adds that care teams need to provide ongoing support to the patient and their loved ones throughout their final days, “never abandoning the patient and respecting their choices.”

Favorite activities or objects can be as important as final medical care. Caregivers should ascertain the tangible and intangible things that would be most pleasing and comforting to the patient in the final days: favorite music or readings, a vase of flowers, a back rub or foot massage, being surrounded by loved ones in quiet or conversation.

Spirituality can help many people find strength and meaning during their final moments. Think about the patient’s preferred spiritual or religious teachings and underpinnings, since ensuring access to this can be especially soothing at the end of life.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!