Medical Assisted Dying

By Hillary Ollenberger

Imagine suffering everyday from severe pain and being told by physicians your condition will only get worse with time. What would you do? Would you start researching treatments, looking for anything to take away a little bit of the suffering? Or would you decide that ending your life is the only option?

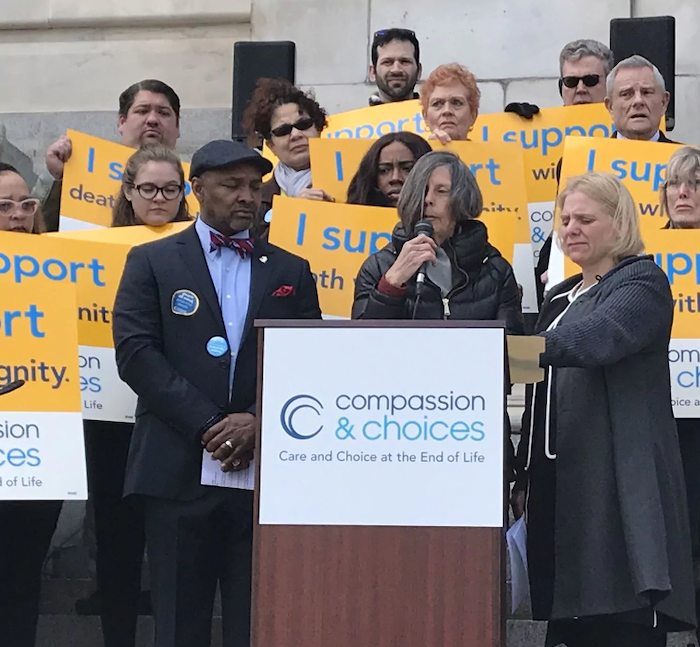

Medical assistance in dying, also known as MAID, is a controversial topic. With medical assisted dying becoming legal across Canada in 2016, there are still many people who do not agree with it.

But Kaitlin Pettit, who lost her father Randy last year, believes that unless you have been in that position, you do not have the right to judge their decision of choosing medical assisted dying.

Randy Pettit, 60, from London, Ont., was suffering from a terminal illness caused by his diabetes that eventually led to heart, kidney, and liver failure. He passed away on Aug. 9th, 2018 with the help of MAID.

“Growing up, my dad was everything I could have wished for in a father,” says Kaitlin. She remembers how her father would always make her laugh and had the best sense of humour.

“He was an extremely hard worker and made sure my sister and I had everything we ever wanted,” she says.

She recalls some of her favourite memories of her dad, including family trips, watching the Toronto Maple Leaf games, and just sitting and chatting with him.

“My father had complications from diabetes,” says Kaitlin. “He always thought he would beat it, we all did. None of us knew how serious it was, but as time progressed, the reality kicked in.”

Randy chose MAID in June of 2018. According to Alberta Health Services, up until Feb. 28th, 2019, there had been a total of 628 MAID deaths in Alberta; this number continues to grow.

“He had discussed it with my mom first before telling my sister and I,” says Kaitlin. “My father did consider other options before he decided he was going to do the medically assisted dying.”

According to the College of Family Physicians of Canada, Quebec became the first province in Canada to pass legislation to allow “medical aid in dying.” The act defines medical aid in dying as “administration by a physician of medications or substances to an end-of-life patient, at the patient’s request, in order to relieve their suffering by hastening death.”

Kaitlin says her father was initially going to pass away naturally. But his illness was spreading quickly to his organs, and he was suffering.

“At first we all had mixed feelings on his decision. Some days we supported him and other days we were hoping we’d wake up and this would all be a bad dream. As the time got closer and we watched him suffer day in and day out, we all began to put our feelings aside and realize what was in the best interest for him.”-Kaitlin Pettit

For a patient who wishes to receive MAID, there are many ethical deliberations that take place with the physician and patient before moving on to the next step.

Dr. Stefanie Green is a MAID provider who assesses patients and provides medical assisted dying in British Columbia. Green says that for a patient seeking MAID, there is a very robust process that takes place.

Green explains that the patient first needs to be the one to ask for the assisted death. The patient then completes a written form that states they requested the assisted death; this has to be witnessed by two independent people who will not benefit from the death or be someone who provides medical care to them.

After the written request is made and witnessed by others properly, there are then two different assessments that need to be done by two separate independent clinicians.

“So that can be either physicians or nurse practitioners, and those clinicians work separately with the patient to see if they’re medically and legally eligible for the care,” says Green. “Once they both agree separately that that’s the case, then the patient can go ahead and set a date to make a plan for an assisted death. It doesn’t mean they have to do it, but that they’re eligible and empowered to do so.”

Rather than calling it euthanasia, Green says that the proper term is MAID, medical assistance in dying.

“It encompasses two different terminologies. One is what’s technically known as assisted suicide, which is when the patient is given the medication and the patient then takes the medication from the clinician and self administers it,” says Green. “But voluntary euthanasia is when the doctor administers the medications themselves, usually through intravenous.”

Green says the vast majority of cases here in Canada, around 99 per cent, have been voluntary euthanasia with the doctor administering medications.

Green says MAID is not just about the patient being able to control their pain and symptoms.

“Most commonly it’s about a patient finding that they have no more meaning in their life and that they’re no longer able to have autonomous activity and find meaning or joy in their life the way that they used to due to their illness.”

Green explains that for the patient, it’s about independence and autonomy.

In order to be eligible for MAID, the patient must meet five specific criteria: they must be over the age of 18; eligible for funding under Canadian health care; suffering from a grievous and irremediable condition; the request for MAID must be voluntary; and their natural death must be in the foreseeable future.

When it comes to a patient choosing MAID, Green says that someone who is suffering from depression without any other symptoms is not eligible.

“In my opinion, a patient who has acute depression does not have the capacity to make this choice because their decision-making capacity is clouded by the mental health,” says Green. “So no, they could not go ahead. There is a set of criteria that must be met, and if they’re not met then the person who provides their care is liable to be prosecuted.”

In terms of individuals who are against MAID, Green says that from her experience, she sees very few people who disagree with this process. Of the 125 cases she has personally assisted, she can only think of a few where a family member was not in agreement with the patient.

“You can imagine that the people who go through this process with me, by definition, are suffering intolerably. What I do see is a lot of relief, and a lot of sadness that they’re going to lose a loved one.” -Dr. Green

Although Green is very passionate about her job, she admits it can be hard. Green says that it takes a lot of time to assess the patient, which also means spending a lot of time getting to know them.

“Quite honestly, I find this work incredibly rewarding,” says Green. “I find that the patients are very grateful for my help and the vast majority of the family members are as well.

So I feel like I’m helping people and I would never help anyone who I don’t believe meets all the criteria.”

Green says that she is comfortable with the work she does and believes she is offering a service for people that is needed and desired.

Although doctors like Green believe MAID is a good option for Canadians, many feel it is unethical and should be illegal.

Alex Schadenberg is the executive director of the Euthanasia Prevention Coalition. Running for over 20 years now, Schadenberg and his team deal with the issues of euthanasia in Canada as well as on an international level.

“I think by the name of the group, you can see I obviously believe that without a question, causing another person’s death, even if they ask for it, is not a good thing.” -Alex Schadenberg.

Schadenberg explains that according to the law, MAID gives power to doctors and nurse practitioners to cause death.

“Not too long ago in Canada, it was considered homicide,” says Schadenberg. “Because we’re not talking about assisted suicide in Canada. We’re talking about euthanasia, lethal injection.”

Schadenberg feels that MAID is a very dangerous concept.

“It’s not about the right to die on their own terms. That’s a misnomer from the beginning,” says Schadenberg. “It’s actually terminology that’s based on a lie. It’s a concept, someone else is killing you. You’ve requested it.”

Schadenberg says three recent reports came up from the Council of Canadian Academics regarding the expansion of euthanasia to children and people with psychiatric conditions.

This is something that is not new to Belgium. With medical assisted dying being legal since 2002, the country also allows medical assisted dying to children. According to the website My Death My Decision, since 2014, competent children can receive euthanasia if they are terminally ill and in great pain.

“This is a very bad concept to be expanding euthanasia to children or to people who have psychiatric conditions,” says Schadenberg. He believes there are a lot of grey areas when it comes to MAID, including Bill C-14, which was put in place on June 17th, 2016.

According to the Government of Canada’s Department of Justice, Bill C-14 allows physicians and nurse practitioners to provide assistance in dying to competent adults who meet the criteria.

Schadenberg feels that Bill C-14 is a sham.

“So what they did is they said Canadians wanted it to be for people with terminal conditions,” says Schadenberg. “So they put that section of the law as, your natural death must be reasonably foreseeable. What does that mean?”

Schadenberg believes that to justify Bill C-14 based on autonomy assumes the patient is not going through great existential, psychological distress.

Dying With Dignity, on the other hand, states that, “although some clinicians interpreted the ‘reasonably foreseeable’ rule to mean a person must be terminally ill, the government specifically stated that that isn’t the case.”

“Caring not Killing” is Schadenberg’s main goal out of all of this. He believes society would be happier if we had good care in place of medically assisted death.

“I don’t think you should ever in society give the power over life and death with somebody else,” says Schadenberg.

Schadenberg is not the only one opposed to MAID. Faith-based hospitals have the right to refuse assisted dying to their patients.

After trying to get into contact with a nurse who works at a faith-based hospital, Leah Janzen, the director of communication from Covenant Health provided a link to their website for answers.

Their policy from CovenantHealth.ca says that:

“While Covenant Health personnel shall neither unnecessarily prolong nor hasten death, the organization nevertheless reaffirms its commitment to provide quality palliative/hospice and end-of-life care, promoting compassionate support for persons in our care and their families.”

Although Covenant Health disagrees with MAID, they still want to give support to their patients who are experiencing any pain or suffering.

They say their goal of care in faith-based hospitals is to reduce suffering and they are “prohibited from participating in any actions of commission or omission that are directly intended to cause death through the deliberate prescribing or administration of a lethal agent.”

Covenant Health could be a good option for patients who are on the fence with MAID but still want to receive support.

But just because someone chooses MAID, does not mean they are necessarily without beliefs or religion.

Kaitlin Pettit says her father was a religious man that prayed a lot.

“My mom’s minister came to our house and visited/prayed with him two days before he passed,” she says.

For her and her family, a place like Covenant Health was not an option.

With his complications from diabetes and his pain increasing, they knew MAID was the right choice.

“He refused to go to hospice and wanted to go on his own terms” she says.

During Randy Pettit’s final days at home, he had nurses and family members check in on him to make sure he was comfortable.

“I know his fight is now over and he is pain-free and that was my only wish for him,” says Kaitlin. “My dad had the privilege to stay at home thanks to his medical team up until the day of his procedure.”

When it was time for Randy to go to the hospital, the paramedics carried him down the stairs and let him sit outside in the sun for 20 minutes; his illness had prevented him from being out of the house for over a year.

“I will never forget that day — we all arrived in trauma, in Maple Leaf jerseys. We had one last drink to cheers what a great father he has been,” says Kaitlin. “It was quite the send-off and I know he was at peace with his decision.”

“As we all said our goodbyes, he looked at us and said, ‘I hope one day you will all understand why I had to do what I am doing.’”

The last thing Kaitlin said to her father was she loved him and was proud of how brave he was.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!