By Jaki Fisher

HAVE you heard the term “death doula”?

You may have. It’s been bandied about a bit recently, after Imogen Bailey recently wrote an article for Mamamia about training to become one.

In the article she mentions that musician Ben Lee is also a death doula.

In case you’re not familiar with the term, a “doula” is traditionally someone who gives support to a woman during pregnancy and during and after the birth.

A death doula is someone who helps at the other end.

Here, Jaki Fisher, an Australian living in Singapore and studying to be a death doula, writes about her first experience witnessing death.

JENNY was the first person who asked me to be with her when she died.

A single woman in her early 50s with only a couple of nephews she was in touch with, Jenny was being cared for at the Assisi hospice in Singapore where I was a volunteer.

Jenny and I talked a lot about what might happen during the dying process and afterwards and it was then that she told me she wanted me to be with her as she died. I said I would do my very best to make this happen.

After several months, Jenny suddenly got quite a lot weaker but at the same time, something in her shifted. I noticed this and asked her if she felt different and she replied that she felt that she was coming to accept what was happening.

She was hardly eating but I remember that when she would have a sip of coffee, her eyes would light up at the taste and she would savour it with delight. And when she went into the garden, she would marvel at the sun and the wind — simple, present joys became very strong for her.

At the end, Jenny deteriorated rapidly. Her breathing changed and it was clear to the nursing staff that she would not live much longer.

Jenny was the first patient at the hospice to take part in an end of life vigilling program, No One Dies Alone (NODA). Based on one that began in the US, theoriginal was started by a nurse called Sandra Clarke who, after leaving a lonely old patient who begged her to stay, returned after her rounds to find he had died alone. She couldn’t forget this and eventually set up this no-fuss, volunteer-run program that has been implemented in many large hospitals across the US.

With most NODA programs in hospitals, volunteers are called to sit with dying people who are alone, estranged from their families or far away from loved ones when they are actively dying.

At Assisi, from the time an alone person is admitted to the hospital, the NODA volunteers become the family and visit them until they were actively dying and then sit in vigil during the last couple of days of their life — if that’s what they wanted.

LAST MOMENTS

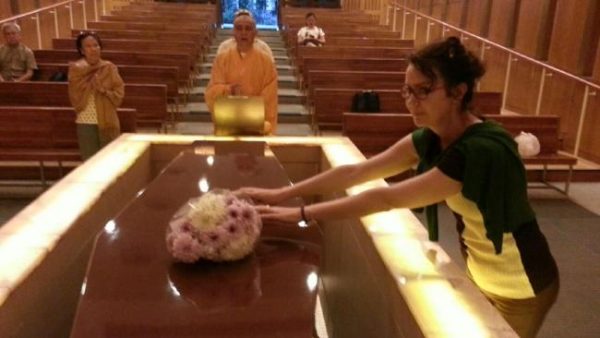

I started the vigil and took the first shift, setting up Jenny’s room with music and soft lights. Jenny was not conscious but I believe she knew I was there. I spoke to her and told her I was there to be with her as she had requested. I remember feeling nervous as I went into the room and initially I felt like I had to ‘do’ things, like read poems or inspiring verses.

Gradually, I took some time to ground and centre myself and create an atmosphere of awareness and presence, as we had learnt in our training. Then, I just focused on really being with Jenny, with no distractions.

I was aware that this was not a normal time, that something big was happening. Jenny had had a fever and when I first sat with her, she was moaning a little. This was unsettling but it also seemed quite normal — I was struck by how OK everything was, even though it was also very sad. In some weird way, as humans, we know how to do this end of life thing. Her breathing became very shallow and there were long pauses between each breath. I remember at one point, I thought that perhaps she had breathed her last breath when suddenly she took a big inhale and I jumped in fright. I sort of laughed to myself and thought that Jenny was again teaching me, reminding me that this was not about me, it was about Jenny and I just tried to relax and be with whatever was happening.

She passed away after only 90 minutes, very gently and softly while I was singing quietly to her. I couldn’t help but think that as usual, she didn’t want there to be a fuss.

We had promised her that she would not be alone when she died, and I was so grateful that we could fulfil that promise.

Being with someone when they die is powerful but it is not frightening. Many people make this comparison, but dying is a bit like labouring to give birth. There are urgent bits and struggling bits and then at the end, it all goes quiet. When Jenny actually died, I hardly even realised, it was so soft, a tender sigh.

After Jenny’s death, her nephew told me that her life had been quite hard and often lonely but that she had shared with him that she was amazed that in her last months of life, when things were really difficult, there was so much love and care in her life.

DEATH DOULAS

In the past two years, the NODA team at Assisi has accompanied more than 10 people during the last months of their lives and sat with them during their final hours. Many of the people we have accompanied lived hard, isolated, rough lives and I wish they could have been otherwise, but at least at the end part, they were loved with no expectations.

My dream is that people all over the world will adopt the NODA program in their own way so that we can all start to look after each other, especially at the end of life.

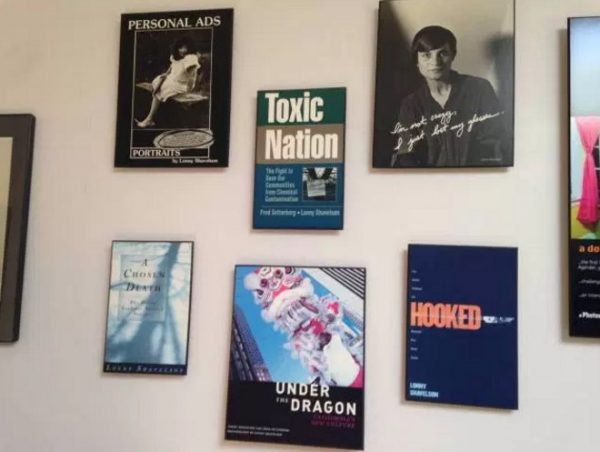

Nowadays, the profession of death doula is garnering a lot of interest. So am I a death doula? I am certainly interested in this area and I am heading off to San Francisco soon to take part in a death doula training and receive certification.

But I have my reservations about this sudden interest and the cynical part of me wonders if it is just the latest trendy thing, like being a yoga teacher was.

However, another part of me celebrates that perhaps this interest might be indicative of people wanting to face their mortality head on. I also like that death doulas are there to help people reclaim death as a natural part of life.

In the past, most people died at home — it was just another of the momentous life events — but in the past 50 years, we’ve pushed it away out of sight.

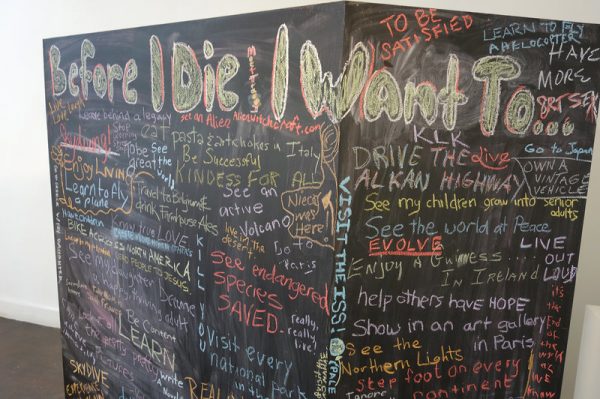

One thing I do want to say is that it is sometimes easy to romanticise dying but it’s not romantic — death is messy, draining, demanding, challenging, funny, heartbreaking, boring — everything … Death is often also really sad and a big loss, so I don’t really feel comfortable about making it a big celebration, unless of course it is!

I’m also wary of the idea of having a “good death” — that kind of creates a weird sort of pressure — like the one that is given to mums when they are striving to have a natural birth at all costs — our death will be what it will be.

However, what I do think is great is that people are talking about end of life and their choices. This conversation is so crucial and helpful and will make the end of life much clearer at a time when things are so rarely clear. However, once again, I wonder about being too attached to a plan — I think death would chuckle wryly at that idea.

To me, being with someone at the time of death is to become intimately exposed to not knowing — it asks us to be fully present and fully OK with whatever happens and not to impose a preconceived idea of what it should be like. To me, accompanying someone at the time of death is not really about doing anything, it’s about being able to hold and be there for whatever. We like to control everything in our lives but death does its own thing … it’s still the biggest mystery in our lives.

‘AN UNNATURAL INTEREST IN DEATH’

I first volunteered at the Assisi Hospice not because of any great altruistic yearning to serve but because I knew that the people there had the inside story about dying. And I had an unnatural interest in death.

I fell into a black swirl of depression at 27 after I tried to fix my face. I went for some kind of noxious peel, a treatment that’s now probably banned. It’s kind of embarrassing — other people get depressed because they lose a loved one or suffer a terrible trauma — me, I thought I’d wrecked my face and down I went into the dark pit. (It’s fine now. Not quite the same but a perfectly serviceable face.)

I was lucky and got treatment and part of the therapy was to do something for others, to forget about “me” for a while. After much sulking and prevaricating I finally started volunteering at the Assisi Hospice.

I still remember the first time I went into the wards and saw my first “dying person” — how tiny and fragile, limbs like little birds, and yet how bright the eyes were.

I didn’t really speak Mandarin, Malay or Tamil (three of Singapore’s four official languages) and most of them didn’t speak English — the 4th one. And yet, those people didn’t just teach me about death, they taught me about life and living.

They taught me about bravery, love, tenacity, dignity and they didn’t seem to mind that I was a self-absorbed, self-destructive girl. They didn’t judge me and they let me see them in all their vulnerability and in this strange suspended time of life. Yes, they were dying but they were also very much alive.

I was supposed to be the do-gooder but they were the ones who taught me and showed me that life is all about moments and all about connection and all about love — and that’s about it.

I moved to the US to study Buddhism and then back to Melbourne but I never forgot the Assisi hospice. In 2012 after reading Being with Dying, a book about accompanying people at the end of life by Roshi Joan Halifax, I attended her Buddhist Chaplaincy program in Santa Fe.

Two years on, I was a Buddhist chaplain and also completed a unit of Clinical Pastoral Education at the Royal Melbourne Hospital.

But I was still volunteering at Assisi and as part of my chaplaincy project helped set up the NODA program.

JENNY’S LEGACY

Jenny spoke openly of her anger and frustration. She had accepted that she did not have long to live but she could not accept that she had to wait so long to die. This was another lesson for us. It was hard not to want to ‘fix’ this and make it better for her. At one time, she wondered what the point of her life was and expressed sadness that there were so many things she hadn’t done. I told her that from my point of view, she was teaching us so much and that she would live on so powerfully for us as our first NODA patient.

I asked her if we could talk about her after she had gone and whether we should change her

name if we did so. She was adamant — if it would help others gain a deeper understanding

about death, then we could certainly go ahead and use her full name with no changes.

We have been running this program for two years now and all of us involved can feel how it has the potential to touch us all and offer something that is greatly needed in

today’s highly medicalised and hurried world — genuine human companionship at the end of

life, especially for those who have no one to give it to them.

Jenny’s life was certainly not in vain. She lives on in the program and touches

every patient we serve. Because of her willingness to embrace NODA, more and more

people have not died alone — this is Jenny’s precious legacy.

Complete Article HERE!