More hospice volunteers, hospitals and individuals are providing end-of-life support

By Gurveen Kaur

The ultimate present you could give a dying person may well be your presence.

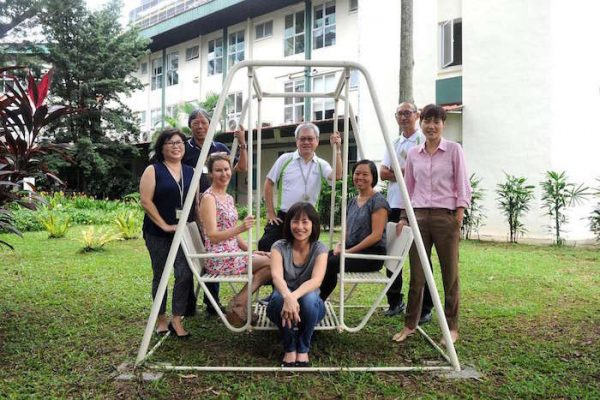

At Assisi Hospice, 15 volunteers take turns to sit by the side of dying patients until their last breath.

They are part of No One Dies Alone, a volunteer-centred programme that provides companionship to dying patients who have neither family nor close friends to accompany them in their final hours.

The volunteers simply provide a comforting presence, lending emotional and psychological support without the help of medical equipment or medication.

At the hospice, it was a long-time volunteer, Ms Jaki Fisher, who suggested the programme in 2013 after hearing about it from a friend in the United States.

The English-language teacher, who is in her 30s, says: “It resonated as I have felt alone before and would not want these patients to feel this way before they die.”

No One Dies Alone was started in 2001 by Ms Sandra Clarke, a nurse in the US, and has been implemented in several hospitals there.

In 2014, she helped implement it at Assisi, whose former chief executive she knew, and also provided training materials. To be a volunteer with the programme, one has to clock at least three months at the hospice and have no recent bereavement in the family in the past six months.

To date, 19 residents have been admitted into the programme. After being identified by medical social workers as suitable candidates – having no family or loved ones – patients are invited to be part of the programme. If they accept, the volunteers will get to know and befriend them.

Once a patient is identified to be in the “active dying” phase, the volunteers each take three-hour shifts to sit by the patient’s bedside and just “be there with the patient”, says Ms Fisher, a Singapore permanent resident who has held vigil 11 times. The period can range from a few hours to a few days.

“It’s a powerful and intense period, even though you might just be sitting there. It’s not about doing something, but being present and there for the person,” she adds.

It can be a trying and emotionally charged process for the volunteers as they must accept that their role is not to help the patient get better.

Housewife Tio Guat Kuan, 51, says: “It was hard initially as we really wanted to help the patient… but then I learnt that the greatest gift you can give anyone is your presence.”

She has held vigil for 11 patients.

Assisi Hospice is the only place here with a fully established No One Dies Alone programme. Other establishments might have other formal programmes that are similar, or depend on staff to be with dying patients instead.

Some hospitals have taken an extra step when it comes to end-of-life care too.

At Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, nurses attend a two-day end-of-life workshop to equip themselves with the skills to counsel and accompany dying patients. These include how to communicate with patients and break bad news to a patient’s family.

Dr James Low, a senior consultant at the hospital’s department of geriatric medicine, says: “Sometimes, all that is needed is a person’s presence in those final hours so they do not feel abandoned. It can be just holding their hand.”

The hospital also has 11 single, air-conditioned rooms where dying patients, identified to be nearing the end, may spend their final hours with their loved ones at no added charge.

Similarly, Tan Tock Seng Hospital has six end-of-life rooms where families can say their last goodbyes in comfort and privacy.

Outside these medical institutions, there are death doulas, or individuals who provide practical and emotional support at the end of life.

It can be a dying person or his family or loved ones who request a doula’s services, which vary from helping to sort out legal paperwork to discussing existential topics on life and death.

In Western countries such as the US, Britain and Australia, the number of these end-of-life guides has been growing in the past five years, although there are no official figures on the industry.

In Singapore, there are few, if any, death doulas.

Certified midwife and birth consultant Red Miller, 38, has been organising workshops since last year to spread the word on the role of a death doula.

The Canadian, who is based in Singapore, invited her friend, Australian death doula Denise Love, to conduct two-day training sessions in November last year and March this year. The first attracted 13 attendees and the second, 26.

One participant was Ms Helen Clare Rozario, founder of Nirvana Mind, a company that offers meditation classes.

The workshop has inspired the 32-year-old to organise a “death cafe”, where people meet to discuss death, as well as a get-together for people who have lost loved ones to suicide.

She says: “The workshop made me think about my best friend’s death two years ago and how I can set up support groups for others who have lost loved ones to talk about the impact of the death.”

Complete Article HERE!