Now is the perfect time to face your fear of mortality. Here’s how.

By Sigal Samuel

Nikki Mirghafori has a fantastically unusual career. After getting a PhD in computer science, she’s spent three decades as an artificial intelligence researcher and scientific advisor to tech startups in Silicon Valley. She’s also spent a bunch of time in Myanmar, training with a Buddhist meditation master in the Theravada tradition. Now she teaches Buddhist meditation internationally, alongside her work as a scientist.

One of Mirghafori’s specialties is maranasati, which means mindfulness of death. Mortality might seem like a scary thing to contemplate — in fact, maybe you’re tempted to stop reading this right now — but that’s exactly why I’d say you should keep reading. Death is something we really don’t like to think or talk about, especially in the West. Yet our fear of mortality is what’s driving so much of our anxiety, especially during this pandemic.

Maybe it’s the prospect of your own mortality that scares you. Or maybe you’re like me, and thinking about the mortality of the people you love is really what’s hard to wrestle with.

Either way, I think now is actually a great time to face that fear, to get on intimate terms with it, so that we can learn how to reduce the suffering it brings into our lives.

I recently spoke with Mirghafori for Future Perfect’s limited-series podcast The Way Through, which is all about mining the world’s rich philosophical and spiritual traditions for guidance that can help us through these challenging times.

In our conversation, Mirghafori outlined the benefits of contemplating our mortality. She then walked me through some specific practices for developing mindfulness of death and working through the fear that can come up around that. Some of them are simple, like reciting a few key sentences each morning, and some of them are more … shall we say… intense.

I think they’re all fascinating ways that Buddhists have generated over the centuries to come to terms with the prospect of death rather than trying to escape it.

You can hear our full conversation in the podcast here. A partial transcript, edited for length and clarity, follows.

Sigal Samuel

You’ve worked in Silicon Valley and you still live near there, so I’m sure you’ve encountered the desire in certain tech circles to live forever. There are biohackers who are taking dozens of supplements every day. Some are getting young blood transfusions, trying to put young people’s blood in their veins to live longer. Some are having their bodies or brains preserved in liquid nitrogen, doing cryopreservation so they can be brought back to life one day. What is your feeling about all these efforts?

Nikki Mirghafori

It’s the quest for immortality and the denial of death. Part of it is natural. Human beings have done this for as long as we have been conscious of the fact that we are mortal.

A person who really put this well was Ernest Becker, the author of the seminal book The Denial of Death. I’d like to offer this quote from him:

This is the paradox. A human is out of nature and hopelessly in it. We are dual. Up in the stars and yet housed in a heart-pumping, breath-gasping body that once belonged to a fish and still carries the gill marks to prove it. A human is literally split in two. We have an awareness of our own splendid uniqueness in that we stick out of nature with a towering majesty, and yet we go back into the ground a few feet in order to blindly and dumbly rot and disappear forever. It is a terrifying dilemma to be in and to have to live with.

There is a whole field of research in psychology called terror management theory, which started from the work of Ernest Becker. This theory says that there’s a basic psychological conflict that arises from having, on the one hand, a self-preservation instinct, and on the other hand, that realization that death is inevitable.

This psychological conflict produces terror. And how human beings manage this terror is either by embracing cultural beliefs or symbolic systems as ways to counter this biological reality, or doing these various things — cryogenics, trying to find elixirs of life, taking lots of supplements or whatnot.

It’s nothing new. The ancient Egyptians almost 4,000 years ago, and ancient Chinese almost 2,000 years ago, both believed that death-defying technology was right around the corner. The zeitgeist is not so different. We think we are more advanced, but it comes from the same fear, same denial of death.

Sigal Samuel

It seems like in the West, we really have a bad case of that denial. I think we rarely talk about death or are willing to face up to the reality that we’re going to die. We seem to be wanting to always distract ourselves from it.

You are a Buddhist practitioner and you have a practice that is very much the opposite of that, which is mindfulness of death, or maranasati. You’ve done trainings and led retreats around this subject. But some people might say this is too morbid and depressing to think about. So before we actually delve into the mindfulness of death practices, could you entice us by telling us a few of the benefits of doing them?

Nikki Mirghafori

First and foremost, what I found for many people, myself included, is that facing the fact that I am not going to live forever really aligns my life with my values.

Most people suffer what’s called the misalignment problem, which is that we don’t quite live according to our values. There was a study that really highlighted this, by a team of scientists, including Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman. They surveyed a group of women and compared how much satisfaction they derived from their daily activities. Among voluntary activities, you’d probably expect that people’s choices would roughly correlate to their satisfaction. You’re choosing to do it, so you’d think that you actually enjoy it.

Guess what? That wasn’t the case. The women reported deriving more satisfaction from prayer, worship, and meditation than from watching television. But the average respondent spent more than five times as long watching television than engaging in spiritual activities that they actually said they enjoyed more.

This is a misalignment problem. There’s a way we want to spend our time, but we don’t do that because we don’t have the sense that time is short, time is precious. And the way to systematically raise the sense of urgency — Buddhism calls it samvega, spiritual urgency — is to bring the scarcity of time front and center in one’s consciousness: I am going to die. This show is not going to go on forever. This is a party on death row.

Sigal Samuel

So the approach here is to bring to the forefront of our consciousness how precious our time is, by impressing upon our minds how scarce it is. And that helps align our life with our values.

Are there other benefits to practicing mindfulness of death?

Nikki Mirghafori

The second benefit is to live without fear of death for our own sake. That way, we don’t engage in typical escape activities. And it frees up a lot of psychic energy. We have more peace, more ease in our lives.

The third benefit is to live without fear of death for the sake of our loved ones. We can support others in their dying process. Usually the challenge of supporting a loved one is that we have a sense of grief for losing them, but a lot of that grief is actually that it’s bringing up fear of our own mortality. So if we have made peace with our own mortality, we can be fully present and support them in their process, which can be a huge gift.

My mom passed away two years ago. And for me, having done all of these practices, I could be with her by her deathbed, holding her hand and supporting her so that she could have a peaceful transition. She didn’t have to take care of me so much and console me. She could be at peace and take delight in this mysterious process that we just don’t know what it’s like. It might be beautiful, might be graceful. We don’t know — there might be nothing; there might be something.

Sigal Samuel

Now I feel sufficiently enticed to learn about the actual practices of mindfulness of death. Let’s start with one that seems simple: the Five Daily Reflections, sometimes called the Five Remembrances, that are often recited in Buddhist circles. Would you mind reciting those?

Nikki Mirghafori

Happy to. These are the Five Daily Reflections that the Buddha suggested people recite every day.

Just like everyone, I am of the nature to age. I have not gone beyond aging.

Just like everyone, I am of the nature to sicken. I have not gone beyond sickness.

Just like everyone, I am subjected to the results of my own actions. I am not free from these karmic effects.

Just like everyone, I am of the nature to die. I have not gone beyond dying.

Just like everyone, all that is mine, beloved and pleasing, will change, will become otherwise, will become separated from me.

Allow whatever arises to come up. It’s okay. These contemplations can bring a lot up. So just be with them as much as possible.

Sigal Samuel

I’ve done these reflections before, but every time I do them, I notice that some are much harder for me to absorb than others. The fourth one — I’m of the nature to die — does not terrify me. Maybe that’s weird, but that’s not the one that really scares me. The one that I find impossibly hard is the fifth one. Everyone that I love and everything that I love is of the nature to change and be separated from me.

It’s really the death or the separation from the people I love that I find much harder to face than the death of myself. Because if I’m going to die, you know, then I’ll be gone. There won’t be any me to miss things.

Nikki Mirghafori

Yes. So appreciate and make space for the one that really touches you.

Also I would say that with the fourth one, making peace with our own death, I’ve done the practice and sometimes I’m like yeah, sure, whatever. And then I’ve really stayed with it, and thought, “This could be my last breath.” When the practice really takes hold and becomes alight with fire, it’s like, “Oh, my God, I am going to die!” It really hits home.

Sigal Samuel

Just to clarify, this is a separate mindfulness of death practice, where you contemplate with every breath, “This could be my last inhale. This could be my last exhale.”

Nikki Mirghafori

Yes. And to bring the historical context into it: This particular teaching is what’s called maranasati. Marana is death in Pali, the language of the Buddha. Sati is mindfulness. The mindfulness of death sutra, that’s where the Buddha taught it, and it’s actually quite a lovely teaching.

The Buddha comes and asks the monks, “How are you practicing mindfulness of death?” And one of them says, “Well, I think I could die in a fortnight, in a couple weeks.” Another one of them says, “Well, I think I could die in 24 hours.” Or “Well, I could die at the end of this meal.” Or “Well, I could die at the end of this bite of food I’m eating.” And another one says, “Well, I could die at the end of this very breath.”

And the Buddha says, “Those of you who said, two weeks, 24 hours, whatever — you are practicing heedlessly. Those who said right at this breath, you are practicing heedfully, correctly. That is the practice.”

There are ways to really bring the sense of immediacy and urgency to all this. It’s not out of the question that there could be an aneurysm or that a meteor could just hit the Earth in this moment. Use visualizations; be creative.

Sigal Samuel

Another thing I find really helpful is remembering the idea of impermanence. Which, of course, is the theme of our whole conversation — that our whole life is impermanent — and that’s a very central Buddhist teaching. But also any emotion that I’m feeling is impermanent. So if I’m feeling an intense surge of fear as I do a practice, that’s impermanent, too.

Nikki Mirghafori

Yeah, I love that. When I teach impermanence, there are little impermanences that come and go, and then there is the big impermanence, which is your life! I’m chuckling because this is a case where impermanence is on your side. Impermanence is just a rule of how things run in this world. It’s impersonal. It’s just the way things are. But in our perspective, it’s either working for us or against us.

Sigal Samuel

Can you tell me about another kind of contemplation — the “corpse contemplation” or “charnel ground contemplation”? Charnel grounds are these places where, after people have died, their bodies are left to decay above ground, to rot in the open air. And Buddhist monks would go and observe them up close, right?

Nikki Mirghafori

Many monks do that, especially in Asia. In order to become more intimate with a sense of mortality, the practice is to go to the charnel ground and to actually see a corpse. And the contemplation is: My body, this alive body, is just like this body that is decaying. It’s in different stages of being a body, of decomposing.

A specific practice in the Buddhist canon is to contemplate a corpse in different stages of decay. This particular practice requires a sense of stability of mind. Do the other ones first. I only teach it on a retreat when there’s a container of safety, holding people and supporting them through it.

Sigal Samuel

I definitely have not yet worked myself up to doing corpse contemplation by looking at images of actual human corpses. But when I go for a walk, whenever I see a dead bird or squirrel or mouse that’s been run over in the road, I actually pause and take a minute to look at it. I’m trying to ease my way into this practice.

Nikki Mirghafori

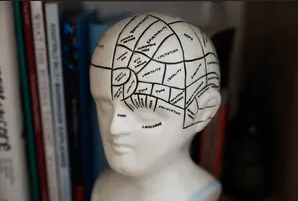

Brilliant. Similarly, another informal practice I wanted to share is having a memento mori. Like a little skull, or those bracelets that are all skulls. I just drew on a little Post-It a skull and bones, and posted it on my computer monitor, so I would remember: Life is short. I’m going to die.

I’ve had various memento moris on my desk throughout the years, and I invite people to have them. They don’t have to be sophisticated. On a piece of paper, just write out, “Life is short” or “You are going to die” or “Traveler, tread lightly.” Whatever works for you to keep death in your perspective. And I think it’s good to switch memento moris around so that your mind doesn’t get used to seeing the same thing all the time.

Sigal Samuel

I’m glad you brought this up because I was going to say the corpse contemplation reminds me a lot of that memento mori tradition, which is a centuries-long tradition in Christianity. So many different religious traditions have emphasized the importance of meditating on our death and have devised ways like the memento mori to try to keep forcing the ego to recognize its looming demise.

Nikki Mirghafori

Yes. And I know that for me, I feel most alive and I feel happiest and I feel most connected with myself, when I’m aware of my death. If it happens for a day or two that it’s not in the forefront for whatever reason, I’m not as bright, as sharp, as alive. So I just love bringing it back. It enlivens me. It supports me to live more fully and hopefully die with more delight and joy and curiosity.

Sigal Samuel

I’m wondering if you can help me with something else. I mentioned earlier that I’m not really scared of my own death so much, but I am scared of the death of the people I love. And especially during the pandemic, I think that’s causing a lot of anxiety for me and probably a lot of others. We’re scared about the potential death of our grandparents, our parents, our friends. Is there a way to free ourselves of the overwhelming fear of their death?

Grief is a natural part of the process. However, it is complicated by our own seen and unseen fear of death. So I invite you to actually work with the practice of making peace with your own death. That’s what’s underlying it. Even if you think you’re not afraid of your own death, you probably are.

When people are really at peace with their own passing, there is a different perspective. There’s a different way of being with the fear or sadness of losing others. There is still a pain of loss, but it shifts.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!