Americans tend to avoid opportunities to engage with their own mortality

By Vittoria Elliott and Kevin McDonald

Halloween in America is awfully cute these days — both in the sense that children’s costumes have reached unimaginable heights of adorability and that the holiday has lost its darkness — and that’s rather awful.

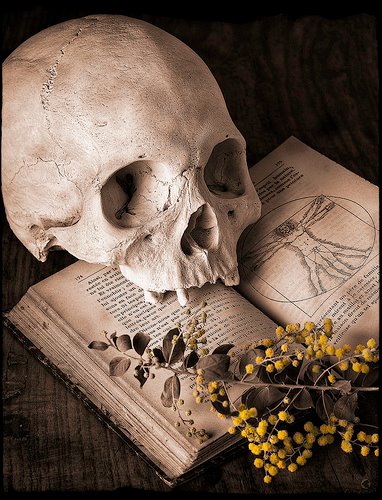

Sexy avocado costumes obscure the holiday’s historical roots and the role it once played in allowing people to engage with mortality. What was once a spiritual practice, like so much else, has become largely commercial. While there is nothing better than a baby dressed as a Gryffindor, Halloween is supposed to be about death, a subject Americans aren’t particularly good at addressing. And nowhere is that more evident than in the way we celebrate (or don’t celebrate) Halloween.

Halloween has its origins in the first millennium A.D. in the Celtic Irish holiday Samhain. According to Lisa Morton, author of “Trick or Treat: A History of Halloween,” Samhain was a New Year’s celebration held in the fall, a sort of seasonal acknowledgment of the annual change from a season of life to one of death. The Celts used Samhain celebrations to settle debts, thin their herds of livestock and appease the spirits: the kinds of preparations one might make if they are genuinely unsure whether they will survive the winter.

But in America today, that kind of acknowledgment of imminent mortality rarely occurs, according to Anita Hannig, an anthropologist and professor at Brandeis University. “When we recognize our mortality, we make preparations for it,” she says, mentioning a Romanian acquaintance who had bought their grandmother a coffin for her birthday. “But in the U.S., that kind of engagement is seen as almost frivolous.”

But what could be less frivolous than talking about a wholly universal experience?

“Every other culture has a time set aside during the year where the dead visit,” said Sarah Chavez, executive director of the Order of the Good Death, a group of funeral industry professionals, academics and artists devoted to preparing a “death phobic culture for their inevitable mortality.” Part of the power of these rituals is to make death into a known quantity, something to be accepted, even embraced, rather than feared.

When Roman Christian missionaries began to convert the Celtic peoples, local holidays were not banished, but rather co-opted. All Saints’ Day, formerly celebrated in mid-May, was moved to Nov. 1 as a way to tame the wild Celtic tradition of Samhain. All Saints’ Day is a celebration of all the dead who have attained heaven in the Catholic tradition, a death-centric celebration if there ever was one.

But the rowdiness of Samhain proved difficult to dislodge, according to Morton, so the Catholic Church tacked on All Souls’ day on Nov. 2, to offer prayers for those who were stuck in purgatory. This three-day celebration began on the evening of Oct. 31, eventually becoming All Hallows’ Evening in reference to the holy days to follow.

When the Spanish colonized what is now Mexico, they used the same strategy, taking indigenous rituals and co-opting them into the church, creating what we know today as Día de los Muertos. In both instances, the holidays retained their focus on the ritualistic recognition of mortality and honoring the dead, with the church as arbiter of the afterlife.

Halloween arrived in the United States in the 1840s, brought by Irish and Scottish immigrants fleeing famine. Popular activities included fortunetelling, speaking with the dead and other forms of divination. (To get a sense of how uncomfortable many Americans are with the dead, try this at your next Halloween party and see what kinds of looks you get.)

Catholic-infused Halloween and Samhain shared several similarities with Día de los Muertos. They were both feast days, filled with candles and a reverence for the dead. The traditional sugar skulls, or calaveras, are similar to Halloween’s “soul cakes,” sweet treats people would offer in exchange for prayers for dead relatives languishing in purgatory.

The calavera tradition remains in the modern form of Día de los Muertos, but in the United States, soul cakes have all but vanished. We now have trick-or-treating, a tradition borne purely out of concerns for the living. In the early part of the 20th century, destructive young pranksters would take full advantage of Halloween, vandalizing and destroying property.

“It was costing cities a lot of money,” says Morton. Instead of banning the holiday altogether, neighborhoods banded together to host parties and give out snacks. “Trick-or-treating was a way of buying kids off.”

Similar to how Halloween has drifted from death ritual to doorbell ringing, modern American engagements with death have changed from up close to a culture of avoidance.

In a lot of ways, Halloween in the United States “mirrors our experience with death directly,” says Chavez.

“We used to take care of our dead in our homes — people used to die at home. We took care of our loved ones, dug their graves. We were there through the entire process. We have no idea what death looks like anymore,” she says. And that ignorance breeds fear, uncertainty and avoidance.

Today, about 80 percent of people die in a hospital or a nursing home. Hannig calls these “institutional deaths,” and they’re just one part of how modern death has been sanitized and sequestered away from the world of the living.

“The responsibilities of death have been outsourced,” she says, adding that hospitals and the mortuary industry allow ordinary people to avoid engagement with the messiness and gruesomeness of death.

“When someone dies in a hospital, oftentimes the body will be whisked away almost immediately and family and friends won’t see it again until after it’s been embalmed.”

And it’s not just dying that modern America is losing touch with; it’s death rituals as well. As the United States becomes increasingly secular, religion’s role in making meaning out of death has shrunk. According to Hannig’s research, memorial services are becoming less and less common, and a collective honoring of the dead — something like All Souls’ Day — is practically nonexistent.

Hannig pointed out that in many other cultures, death is a community affair and something people prepare for together. In certain Buddhist communities in Nepal, for instance, when someone dies they will be surrounded by their loved ones and valued possessions to make sure they don’t have any longed-for attachment tying them to life. It’s a way for both parties — the dying and the living — to accept and let go.

Instead, modern Halloween focuses on the creepy and the capitalistic. “We consume death in a commercialized, entertainment way,” says Chavez. By making death fantastical, we make it feel almost impossible, and therefore less threatening. “We know that a zombie movie isn’t realistic. It’s all a way that we can reassure ourselves that we are safe and it won’t happen to us.”

But haunted attractions, horror films and safety from zombies haven’t made us less afraid of death. If anything, by continuing to keep death at a distance, we transform it into an unknown: possibly the scariest thing of all.