By Andrew MacPherson and Ravi B. Parikh

[W]here do you want to die? When asked, the vast majority of Americans answer with two words: “At home.”

Despite living in a country that delivers some of the best health care in the world, we often settle for end-of-life care that is inconsistent with our wishes and administered in settings that are unfamiliar, even dangerous. In California, for example, 70 percent of individuals surveyed said they wish to die at home, yet 68 percent do not.

Instead, many of us die in hospitals, subject to overmedication and infection, often after receiving treatment that we do not want. Doctors know this, which may explain why 72 percent of them die at home.

Using data from the Dartmouth Atlas — a source of information and analytics that organizes Medicare data by a variety of indicators linked to medical resource use — we recently ranked geographic areas based on markers of end-of-life care quality, including deaths in the hospital and number of physicians seen in the last year of life. People are accustomed to ranking areas of the country based on availability of high-quality arts, universities, restaurants, parks and recreation and health-care quality overall. But we can also rank areas based on how they treat us at an important moment of life: when it’s coming to an end.

It turns out not all areas are created equal. Critical questions abound. For example, why do 71 percent of those who die in Ogden, Utah, receive hospice care, while only 31 percent do in Manhattan? Why is the rate of deaths in intensive care units in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, almost four times that of Los Angeles? Why do only 12 percent of individuals in Sun City, Ariz., die in a hospital, while 30 percent do in McAllen, Texas?

Race and other demographics in a given area certainly matter. One systematic review of more than 20 studies showed that African American and Hispanic individuals utilize advance-care planning and hospice far less than whites. More research is needed to explore these differences and to close these gaps and demand high-quality, personalized care for people of all races.

But race and demographics don’t provide all the answers. For instance, Sarasota and St. Petersburg, Fla., are only 45 miles apart and have similar ethnic demographics. Yet we found that they score quite differently on several key quality metrics at the end of life.

A variety of factors probably contribute to our findings. Hospice, which for 35 years has provided team-based care, usually at home, to those nearing the end of life and remains enormously successful and popular, is underutilized. Most people enroll in hospice fewer than 20 days before death, despite a Medicare benefit that allows patients to stay for up to six months. Hospice enrollment has been shown to be highly dependent on the type of doctor that you see. In fact, one study among cancer patients with poor prognoses showed that physician characteristics (specialty, experience with practicing in an inpatient setting, experience at hospitals, etc.) mattered much more than patient characteristics (age, gender, race, etc.) in determining whether patients enrolled in hospice. For example, oncologists and doctors practicing at nonprofit hospitals were far more likely than other doctors to recommend hospice.

Also, physicians in a given geographic area are likely to have similar approaches to health care. They may collectively differ from physicians in another area in their familiarity and comfort with offering hospice care to a patient. This may explain why hospice enrollment significantly varies among geographic regions.

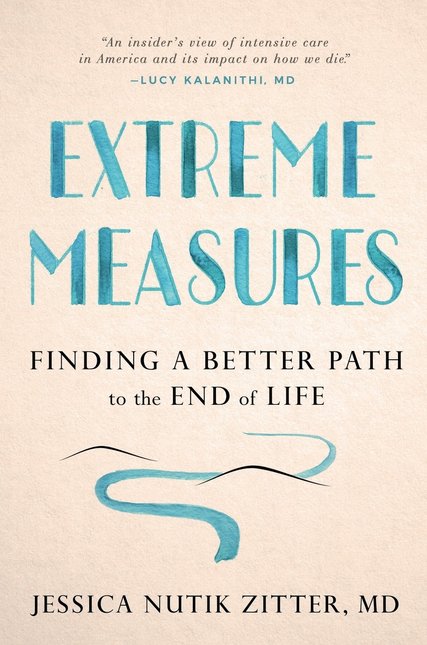

Palliative care, which focuses on alleviation of suffering, is often misunderstood by doctors as giving up. Health professionals’ lack of longitudinal, substantive training in end-of-life care only compounds the problem.

Perhaps most important, fewer than half of Americans have had a conversation about their end-of-life wishes — a process known as advance care planning — and only one-third have expressed those wishes in writing for a health-care provider to follow when they become seriously ill. If people do not have a clear sense of their end-of-life wishes, it is easy to imagine that they may be swayed by a physician’s recommendation.

The private sector has led the way in addressing the underutilization of hospice and improving end-of-life care. For instance, health insurers such as Aetna have devised programs integrating nurse-led case management services for seriously ill individuals, reducing costly and undesired emergency room visits while increasing appropriate hospice referrals. And start-ups including Aspire Health are working with communities to provide palliative care in people’s homes while devising algorithms to help payers and providers identify individuals who might benefit from palliative and hospice care.

Congress also is considering bipartisan solutions consistent with best practices. Congressional leaders have recently introduced several pieces of legislation that would test new models of care for those facing advanced illness, support health professionals in training for end-of-life care and ensure that barriers are removed for consumers to access care.

And Medicare, via its Innovation Center, has led the way in testing promising care models to support those at the end of life, including the Medicare Care Choices Model, which allows individuals to receive hospice care alongside traditional, curative treatment.

But the secret sauce may be a shift in culture. We will not improve the death experience until we demand that our public- and private-sector leaders act and that our local health professionals encourage person-centered end-of-life care.

As with any social change, progress will be driven by a growing awareness and a desire for justice among families and patients. There are good and bad places to die in America. However, to ensure a better death for all, we must confront not just geographic disparities but also our resistance to thinking about death.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!