“Katy Butler is the author of “The Art of Dying Well,” from which this essay was excerpted in Tricycle magazine. (C) 2019 Katy Butler.”

What does it look like to die well?

By Katy Butler

If someone you love has died in a hospital, you may have seen modern death at its worst: overly medicalized, impersonal, and filled with unnecessary suffering. The experience can be a bitter lesson in Buddha’s most basic teaching: the more we try to avoid suffering (including death), the worse we often make it.

Even though roughly half of Americans die in hospitals and other institutions, most of us yearn to die at home, and perhaps to experience our leavetaking as a sacred rite of passage rather than a technological flail. You don’t have to be a saint, or be wealthy, or have a Rolodex of influential names to die well. But you do need to prepare. It helps to be a member of at least one “tribe,” to have someone who cares deeply about you, and to have doctors who tell you necessary truths so that you can decide when to stop aggressive treatment and opt for hospice care. Then those who care for you can arrange the basics: privacy, cleanliness, and quiet, the removal of beeping technologies, and adequate pain control. They can listen and express their love, and provide the hands-on bedside care hospice doesn’t cover.

From then on, a more realistic hope for our caregivers, and for ourselves when we are dying, may not be an idealized “good death” by a well-behaved patient, but a “good enough death,” where we keep the dying as comfortable and pain-free as possible, and leave room for the beautiful and the transcendent—which may or may not occur.

Hospice professionals often warn against high expectations. Things will probably not go as planned, and there comes a point when radical acceptance is far more important than goal-oriented activity. They don’t like the idea, inherent in some notions of the “good death,” of expecting the dying to put on a final ritual performance for the living, one marked by beautiful last words, final reconciliations, philosophical acceptance of the coming of death, lack of fear, and a peaceful letting go.

“I don’t tell families at the outset that their experience can be life-affirming, and leave them with positive feelings and memories,” said hospice nurse Jerry Soucy. “I say instead that we’re going to do all we can to make the best of a difficult situation, because that’s what we confront. The positive feelings sometimes happen in the moment, but are more likely to be of comfort in the days and months after a death.” This is what it took, and how it looked, for the family of John Masterson.

John was an artist and sign painter, the ninth of ten children born to a devout Catholic couple in Davenport, Iowa. His mother died when he was 8, and he and two of his sisters spent nearly a year in an orphanage. He moved to Seattle in his twenties, earned a black belt in karate, started a sign-painting business, and converted to Nichiren Shoshu, the branch of Buddhism whose primary practice is chanting. He never left his house without intoning three times in Japanese Nam Myoho Renge Kyo (“I Honor the Impeccable Teachings of the Lotus Sutra”).

He was 57 and living alone, without health insurance, when he developed multiple myeloma, an incurable blood cancer. He didn’t have much money: he was the kind of person who would spend hours teaching a fellow artist how to apply gold leaf, while falling behind on his paid work. But thanks to his large extended family, his karate practice, and his fierce dedication to his religion, he was part of several tribes. He was devoted to his three children—each the result of a serious relationship with a different woman—and they loved him equally fiercely. His youngest sister, Anne, a nurse who had followed him to Seattle, said he had “an uncanny ability to piss people off but make them love him loyally forever.”

When he first started feeling exhausted and looking gaunt, John tried to cure himself with herbs and chanting. By the time Anne got him to a doctor, he had a tumor the size of a half grapefruit protruding from his breastbone. Myeloma is sometimes called a “smoldering” cancer, because it can lie dormant for years. By the time John’s was diagnosed, his was in flames.

Huge plasma cells were piling up in his bone marrow, while other rogue blood cells dissolved bone and dumped calcium into his bloodstream, damaging his kidneys and brain function. He grew too weak and confused to work or drive. Bills piled up and his house fell into foreclosure. Anne, who worked the evening shift at a local hospital, moved him into her house and drove him to various government offices to apply for food stamps, Social Security Disability, and Medicaid. She would frequently get up early to stand in line outside social services offices with his paperwork in a portable plastic file box.

Medicaid paid for the drug thalidomide, which cleared the calcium from John’s bloodstream and helped his brain and kidneys recover. A blood cancer specialist at the University of Washington Medical Center told him that a bone marrow transplant might buy him time, perhaps even years. But myeloma eventually returns; the transplant doesn’t cure it. The treatment would temporarily destroy his immune system, could kill him, and would require weeks of recovery in sterile isolation. John decided against it, and was equally adamant that he’d never go on dialysis.

After six months on thalidomide, John recovered enough to move into a government-subsidized studio apartment near Pike Place Market. He loved being on his own again and wandered the market making videos of street musicians, which he’d post on Facebook. But Anne now had to drive across town to shop, cook, and clean for him.

The health plateau lasted more than a year. But by the fall of 2010, John could no longer bear one of thalidomide’s most difficult side effects, agonizing neuropathic foot pain. When he stopped taking the drug, he knew that calcium would once again build up in his bloodstream, and that he was turning toward his death.

An older sister and brother flew out from Iowa to help Anne care for him. One sibling would spend the night, and another, or John’s oldest daughter, Keely, a law student, would spend the day.

Christmas came and went. His sister Irene returned to Iowa and was replaced by another Iowa sister, Dottie, a devout Catholic. In early January, John developed a urinary tract infection and became severely constipated and unable to pee. Anne took him to the University of Washington Medical Center for what turned out to be the last time. His kidneys were failing and his bones so eaten away by disease that when he sneezed, he broke several ribs. Before he left the hospital, John met with a hematologist, a blood specialist, who asked Anne to step briefly out of the room.

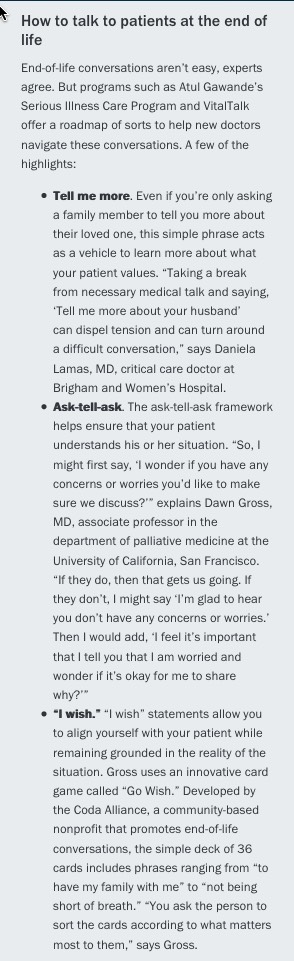

Anne does not know exactly what was said. But most UW doctors are well trained in difficult conversations, thanks to a morally responsible institutional culture on end-of-life issues. Doctors at UW do not simply present patients with retail options, like items on a menu, and expect them to blindly pick. Its doctors believe they have an obligation to use their clinical experience to act in their patients’ best interests, and they are not afraid of making frank recommendations against futile and painful end-of-life treatments. When the meeting was over, the doctor told Anne that her brother “wanted to let nature take its course.” He would enroll in hospice. Anne drove him home.

John knew he was dying. He told Anne that he wanted to “feel everything” about the process, even the pain. He took what she called “this Buddhist perspective that if he suffered he would wipe out his bad karma. I said, ‘Nah, that’s just bullshit. You’ve done nothing wrong. The idea that we’re sinners or have to suffer is ludicrous.’” She looked her brother in the eye. She knew she was going to be dispensing his medications when he no longer could, and she wasn’t going to let him suffer. She told him, ‘You’re not going to have a choice.’”

“Last Touch”

Anne said she “set an intention”: not to resist her brother’s dying, but to give him the most gentle death possible and to just let things unfold. On January 15, her birthday, she and John and a gaggle of other family members walked down to Pike Place Market to get a coffee and celebrate. John was barely able to walk: Anne kept close to him so that she could grab him if he fell. It was the last time he left the house.

The next morning, a Sunday, while Anne was sitting with John at his worktable, he looked out the window and asked her, “Do you think I’ll die today?” Anne said, “Well, Sundays are good days to die, but no, I don’t think it’s today.” It was the last fully coherent conversation she had with him.

He spent most of his last nine days in bed, as his kidneys failed and he grew increasingly confused. He didn’t seem afraid, but he was sometimes grumpy. He had increasing difficulty finding words and craved celery, which he called “the green thing.” He would ask Anne to take him to the bathroom, and then forget what he was supposed to do there. His daughter Keely took a leave of absence from law school, and Anne did the same from her job at the hospital. Fellow artists, fellow chanters, former students to whom he’d taught karate, nephews, nieces, and sign-painting clients visited, and Anne would prop him up on pillows to greet them.

Anne managed things, but with a light hand. She didn’t vet visitors, and they came at all hours. If she needed to change his sheets or turn him, she would ask whoever was there to help her, and show them how. That way, she knew that other people were capable of caring for him when she wasn’t there. “The ones that have the hardest time [with death] wring their hands and think they don’t know what to do,” she said. “But we do know what to do. Just think: If it were my body, what would I want? One of the worst things, when we’re grieving, is the sense that I didn’t do enough,” she said. “But if you get in and help, you won’t have that sense of helplessness.”

Each day John ate and spoke less and slept more, until he lost consciousness and stopped speaking entirely. To keep him from developing bedsores, Anne would turn him from one side to the other every two hours, change his diaper if necessary, and clean him, with the help of whoever was in the room. He’d groan when she moved him, so about a half an hour beforehand, she’d crush morphine and Ativan pills, mix them with water as the hospice nurse had showed her, and drip them into John’s mouth.

One morning her distraught brother Steve accused her of “killing” John by giving him too much morphine—a common fear among relatives, who sometimes can’t bear to up the dose as pain gets worse. At that moment, the hospice nurse arrived by chance, and calmly and gently explained to Steve, “Your brother is dying, and this is what dying looks like.”

The death was communal. People flowed in and out, night and day, talking of what they loved about John and things that annoyed them, bringing food, flowers, candles, and photographs until John’s worktable looked like a crowded altar. Buddhists lit incense and chanted. Someone set up a phone tree, someone else made arrangements with a funeral home, and one of the Buddhists planned the memorial service.

Most of the organizing, however, fell to Anne. It may take a village to die well, but it also takes one strong person willing to take ownership—the human equivalent of the central pole holding up a circus tent. In the final two weeks, she was in almost superhuman motion. She leaned in, she said, “into an element of the universe that knows more than I know. I was making it up as I went along. People contributed and it became very rich.

“That’s not to say there weren’t times when it was phenomenally stressful. I was dealing with all the logistics, and with my own mixed emotions about my brother. I was flooded with memories of our very complicated relationship, and at the same time I knew my intention was that he be laid to rest in the most gentle way possible.”

Hospice was a quiet support in the background. Over the two years of his illness, John’s care had perfectly integrated the medical and the practical, shifting seamlessly from prolonging his life and improving his functioning— as thalidomide and the doctors at UW had done—to relieving his suffering and attending his dying, as the hospice nurses and those who loved him had done.

There were no demons under the bed or angels above the headboard. Nor were there beeping monitors and high-tech machines. His dying was labor-intensive, as are most home deaths, and it was not without conflict.

A few days before he died, two siblings beseeched Anne to call a priest to give John last rites in the Catholic church. “It was a point of love for my siblings. They were concerned that John was going to burn in hell,” Anne said. “But John hated priests.” In tears, Anne called the Seattle church that handled such requests, and the priest, after a brief conversation, asked her to put her sister Dottie on the phone. Yes, Dottie acknowledged, John was a Buddhist. No, he hadn’t requested the sacraments. Yes, his children were adamantly opposed. No, the priest told her, under the circumstances he couldn’t come. It wasn’t John’s wish.

Ten days after the family’s last walk through Pike Place Market, the hospice nurse examined John early one morning and said, “He won’t be here tomorrow.” She was seeing incontrovertible physical signs: John’s lips and fingertips were blue and mottled. He hadn’t opened his eyes in days. His breathing was labored and irregular, but still oddly rhythmic, and he looked peaceful. The hospice nurse left. Anne, helped by John’s daughter Keely and his sister Dottie, washed and turned John and gave him his meds. Then they sat by his side. Anne had her hand on his lap.

“It was January in Seattle,” Anne said. “The sun was coming through the window and we could hear the market below beginning to wake up. We were just the three of us, talking and sharing our stories about him and the things we loved and didn’t love, the things that had pissed us off but now we laughed about. I can’t ever, in words, express the sweetness of that moment.

“It was January in Seattle,” Anne said. “The sun was coming through the window and we could hear the market below beginning to wake up. We were just the three of us, talking and sharing our stories about him and the things we loved and didn’t love, the things that had pissed us off but now we laughed about. I can’t ever, in words, express the sweetness of that moment.

“He just had this one-room apartment with a little half-wall before the kitchen. I walked over to put water on to make coffee, and Keely said, ‘His breathing’s changed.’”Anne stopped, ran over, sat on the bed, and lifted her brother to a sitting position. He was light. She held him close, and during his last three breaths she chanted Nam Myoho Renge Kyo, as her brother had always done, three times, whenever he left his house. “I was really almost mouth-to-mouth chanting, and he died in my arms,” she said. “We just held him, and then my sister Dottie said her prayers over him.”

Anne sat next to her brother and said, “John, I did well.”

“I know he would not have been able to orchestrate it any better than how it unfolded,” she said.

“It was a profound experience for me. I realized what a good death could be.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

accredits medical schools, does not require clinical rotations or courses on palliative medicine or end-of-life care. Part of the issue is that these skills “can’t be taught through lectures and demonstrations,” says Susan Block, MD, a professor of psychiatry and medicine at Harvard Medical School. “The only way to improve competencies is through field practice and feedback.”

accredits medical schools, does not require clinical rotations or courses on palliative medicine or end-of-life care. Part of the issue is that these skills “can’t be taught through lectures and demonstrations,” says Susan Block, MD, a professor of psychiatry and medicine at Harvard Medical School. “The only way to improve competencies is through field practice and feedback.”