A majority of Massachusetts voters seem to be in favor of two controversial ballot initiatives that supporters say would ease the suffering of ill Massachusetts citizens.

Sixty percent of Bay State voters said they support allowing terminally ill people to legally obtain medication to end their lives, according to the latest survey from Western New England University Polling Institute in partnership with The Republican and MassLive.com.

Sixty-four percent of voters, meanwhile, backed legalizing the use of marijuana for medical purposes and 27 percent opposed the idea, according to the survey of 504 registered voters conducted from May 29 to 31.

Under state law, more than 68,000 certified voters must sign an initial petition to place an issue on the November ballot, with not more one-quarter of all the signatures coming from the same county. If the legislature does not take up the issue, an additional 11,000-plus signatures are needed by June 19th to put it on the ballot.

So as long as the initiatives fulfill the legal requirements, Massachusetts voters will have their say on the respective issues on election day.

“Polling on ballot questions is tricky because responses can be highly sensitive to question wording,” said Tim Vercellotti, associate professor of political science and director of the Polling Institute at Western New England University. “The actual questions that the voters see on the ballot tend to be longer and more complicated. Our questions attempt to get to the essence of each issue.”

The survey asked voters whether they supported or opposed “allowing people who are dying to legally obtain medication that they could use to end their lives,” according to Vercellotti.

Support for the “death with dignity” proposal outnumbered opposition by a margin of two to one in the Western New England University survey, with 60 percent of voters saying they support the idea, 29 percent opposing it and 11 percent saying they did not know or declining to provide a response.

John, a former high school teacher living in Holyoke who asked not to be identified by his last name, said his family’s experiences with cancer and other terminal illnesses shaped his support of the “death with dignity” option.

“I think it should be a matter of personal choice,” he said. “If someone is at the end of their life with a terminal illness and it may continue for six months or a year with terrible suffering and pain, why not give them the option? To me, it is freedom of choice.”

And although John identifies as Catholic, he said that he does not attend services and his religion holds no impact on his stance on the subject.

According to the data, opinions varied along party lines, with 67 percent of Democrats favoring the proposal, compared to 58 percent of independents and 53 percent of Republicans.

Support for the measure also varied by age, Vercellotti said.

While 61 percent of voters ages 18 to 49 and 72 percent of voters ages 50 to 64 support the idea, the same was true for only 46 percent of voters ages 65 and older.

Respondents who were 65 and older also were the most likely of any demographic group to say they were not sure or to decline to answer the question, with 20 percent choosing those options.

“I told them I didn’t know because I didn’t want to just give a quick answer. It’s a complicated issue,” said Robert Sandwald, a retired resident of Hopkinton, Mass. “I don’t want to give an answer I believe in. I’ll be thinking about it in case someone asks me in the future but I just don’t know how I feel about it.”

Views about the “death with dignity” proposal also varied by religion and religious observance.

Vercellotti said that although a majority of Catholic and Protestant voters said they support the proposal, their opinions tend to vary based on how often they attend religious services.

Fifty-two percent of all Catholic voters said they support the idea, 36 percent said they oppose it, and 12 percent said they did not know or declined to answer. But among Catholic voters who attend church at least once a week or almost every week, 52 percent opposed the “death with dignity” proposal and only 37 percent said they support it.

Deborah Greene, a 56-year-old Catholic from Milton who said she attends church services almost every week, opposes the “death with dignity” option.

“I’m against it because I just don’t think it’s right,” Greene said. “It is a religious conflict.”

Catholic voters who attend church less frequently – about once a month, seldom or never – backed the idea by more than a two-to-one margin, 62 percent to 25 percent.

Among all Protestant voters, 56 percent supported the proposal, and 28 percent were opposed. Opinion was much more narrowly divided among Protestant voters who attend services at least once a week or almost every week, with 42 percent opposed and 38 percent in favor.

“The results indicate that religious identity is not the only distinguishing factor when it comes to views on this issue,” Vercellotti said. “Responses varied not just by religious identity, but also by religious observance. When it comes to Catholics and Protestants, the more ‘churched’ you are, so to speak, the more likely you are to oppose the ‘death with dignity’ proposal.”

Voters from other religious backgrounds overwhelmingly supported the measure, with 76 percent in favor and 19 percent opposed. Voters who identified themselves as atheists or agnostic backed the idea by an almost nine-to-one margin.

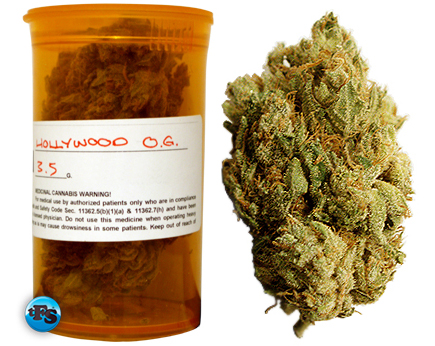

On the topic of allowing people to obtain marijuana for medical purposes with the prescription of a licensed physician, the results varied by political affiliation, gender, age and education level.

If the proposed law legalizing medical marijuana appears on the ballot and is approved by a majority of voters on Nov. 6, then Massachusetts would join 16 other states in the U.S. by allowing such a treatment option, despite federal law which prohibits it.

The proposed law would allow a physician to prescribe a 60-day supply of marijuana to a patient with a “debilitating medical condition,” such as cancer, AIDS, Parkinson’s disease or a broad category that includes “other conditions.”

The law would also permit up to 35 nonprofit medical marijuana dispensaries or treatment centers across the state, including at least one in each county.

The idea of legalized medical marijuana in Massachusetts has stirred passionate conversation among the commonwealth’s citizens and legislators.

John, the former high school teacher in Holyoke, said he opposes medical marijuana primarily because of the possibility of it being a precursor to full legalization.

“When I was a teacher, I saw the destruction that marijuana caused in the lives of so many young people,” he said. “I’ve seen kids with a tremendous amount of potential just go down the tubes. And I know you can’t completely blame it on marijuana, but it was a contributing factor. I guess I’m opposed to this if it is opening the door to overall legalization.”

Greene, a devout Catholic, said she is open to the concept because of research on the issue.

“As I understand it, there are properties in marijuana that can ease the pain of cancer that come with certain developments in the disease,” Greene said. “So as I understand it, it would be beneficial under medical direction, so I’m open to that.”

When asked whether they would support or oppose legalizing the use of marijuana for medical purposes, 74 percent of Democrats and 62 percent of independents endorsed the measure, while Republican voters were almost evenly divided, with 47 percent opposed and 45 percent in favor.

More than two-thirds of female voters supported legalizing medical marijuana, while the same was true for 58 percent of male voters. Younger voters also responded more favorably than did senior citizens. Sixty-eight percent of voters ages 18 to 49 and 50 to 64 supported legalizing medical marijuana compared to 54 percent of voters age 65 and older.

Views also varied by education, with 68 percent of voters with college degrees endorsing the measure, compared to 61 percent of voters with some college or with a high school diploma or less.

The survey has a 4.4. percent margin of error.

Complete Article HERE!