— Nancy Meredith, November 1987

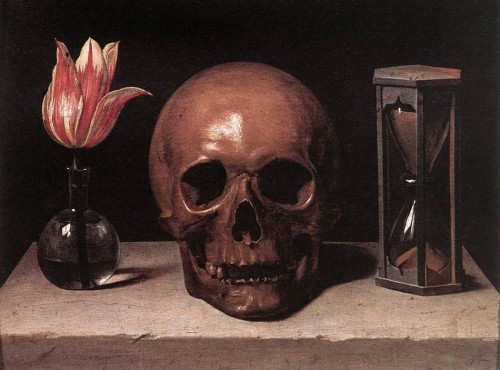

Death vs Dying

It’s not as if they are the same thing. Dying is still warm, still connected to life as we know it. Death is cold. Dying is letting go. Death is being gone. Death is something I don’t know anything about, except that embalmed bodies are poor representations of the people who once animated them. Neither is anything I like to think about. So I figure they are probably topics I should give some attention to, to try to write some of the feelings they engender.

If I Should Die Before I Wake

It was only recently that I realized how early I had lay me down to sleep. I began very late in life the struggle to wake up from the soft comfort of my habits and routines. It’s hard getting up out of a warm bed when you don’t know what the weather’s like outside.

Coming to Terms with Mortality

Thinking about my own death feels different from thinking about someone else’s, but both feel lonely. Both bring on a panicky “No! Not yet!” When I’m confronted with the death of someone who has touched my life, the feeling is that I should have done more, that there is unfinished business here. Guilt confused with feeling that we don’t always get dealt a fair hand.It’s easier to die symbolically than to be symbolically dead. I can imagine ways I mightdie, my reluctance to leave tempered with the need to comfort those I leave behind. There’s a bit of poignancy about it, bittersweet and loving. And I am still (somewhat) in control.But I have trouble going beyond dying to death. I am responsible for so much and so many right now. Who will do the work I’ll have left undone? Who will take care of the people I love and all the little things in my life to which I attach so much importance? Who will feed my cat? If I try this exercise long enough I sometimes experience a moment of clarity and a fresh perspective on what’s really important to do today, right now. But it’s never long before I tighten up with a renewed sense of urgency to do more, faster. When I notice reminders of my own mortality—a bleeding mole, tightness in my chest, recurring asthma—I inevitably resist. “No, not yet! I have too much to do!”

I don’t think I want to live forever. When I hear people speak of the immortality of the physical body as a viable option, I feel somewhat embarrassed, as I am by the part of the

Apostles’ Creed that avows belief in the resurrection of the body. My resistance to my own death seems to be not so much a reluctance to leave my body as an unwillingness to relinquish control. To trust that the people I love can get along without me very well.

Just Moving On

Dying must be a lot like moving from one place to another. I’ve said goodbye many times in my life. Life goes on—for me and for those I leave behind. But it feels lonely, especially at first, and the nostalgia for past lives never completely disappears.

A Taste of Humility

Raymond Kaiser observed that the bottom line about death is that sooner or later people are going to say “So what?” No matter how important you are in their lives right now, no matter how wonderful you are, they’re going to come to a place where they accept your

Mini-Deathsabsence and proceed with business as usual. Trying to experience how that feels is an exercise in humility. It defeats arrogance and renews trust in others and faith in the continuity of life.

Whenever I think of death—particularly my own—I feel lonely. On the other hand, all the dark, lonely times I create for myself are deaths of a kind. Whenever I allow myself to feel alone, detached from those around me, I am already, for a time, dead. I am saying No to life and embracing Not Life. Lately I’ve tried to bring the light of consciousness to these times, to experience them as mini-deaths, with the benefit of then being able to embrace life more fully. I emerge from the dark more sensitive to my connection with others in my life, more aware of their feelings, more caring about their needs. I am more present. Perhaps the value in practicing death is not so much to be able to die better, but to be able to live better.

Judgment

I don’t like death, and I cannot embrace it as “moving on to a better place.” I don’t like acknowledging its inevitability. I tremble before it. It constitutes, after all, a fall into the unknown. I recently signed up to be a Hospice volunteer. Maybe by helping others deal with imminent death—their own or that of someone they love—I can learn to look at death squarely and say, “So what?” but I don’t think I’ll ever like it.