Life is a bitch. Then you die. So while staring at my navel the other day, I decided that that bitch happens in four stages. Here they are.

Stage One: Mimicry

We are born helpless. We can’t walk, can’t talk, can’t feed ourselves, can’t even do our own damn taxes.

As children, the way we’re wired to learn is by watching and mimicking others. First we learn to do physical skills like walk and talk. Then we develop social skills by watching and mimicking our peers around us. Then, finally, in late childhood, we learn to adapt to our culture by observing the rules and norms around us and trying to behave in such a way that is generally considered acceptable by society.

The goal of Stage One is to teach us how to function within society so that we can be autonomous, self-sufficient adults. The idea is that the adults in the community around us help us to reach this point through supporting our ability to make decisions and take action ourselves.

But some adults and community members around us suck.1 They punish us for our independence. They don’t support our decisions. And therefore we don’t develop autonomy. We get stuck in Stage One, endlessly mimicking those around us, endlessly attempting to please all so that we might not be judged.2

In a “normal” healthy individual, Stage One will last until late adolescence and early adulthood.3 For some people, it may last further into adulthood. A select few wake up one day at age 45 realizing they’ve never actually lived for themselves and wonder where the hell the years went.

This is Stage One. The mimicry. The constant search for approval and validation. The absence of independent thought and personal values.

We must be aware of the standards and expectations of those around us. But we must also become strong enough to act in spite of those standards and expectations when we feel it is necessary. We must develop the ability to act by ourselves and for ourselves.

Stage Two: Self-Discovery

In Stage One, we learn to fit in with the people and culture around us. Stage Two is about learning what makes us different from the people and culture around us. Stage Two requires us to begin making decisions for ourselves, to test ourselves, and to understand ourselves and what makes us unique.

Stage Two involves a lot of trial-and-error and experimentation. We experiment with living in new places, hanging out with new people, imbibing new substances, and playing with new people’s orifices.

In my Stage Two, I ran off and visited fifty-something countries. My brother’s Stage Two was diving headfirst into the political system in Washington DC. Everyone’s Stage Two is slightly different because every one of us is slightly different.

Stage Two is a process of self-discovery. We try things. Some of them go well. Some of them don’t. The goal is to stick with the ones that go well and move on.

Stage Two is a process of self-discovery. We try things. Some of them go well. Some of them don’t. The goal is to stick with the ones that go well and move on.

Stage Two lasts until we begin to run up against our own limitations. This doesn’t sit well with many people. But despite what Oprah and Deepak Chopra may tell you, discovering your own limitations is a good and healthy thing.

You’re just going to be bad at some things, no matter how hard you try. And you need to know what they are. I am not genetically inclined to ever excel at anything athletic whatsoever. It sucked for me to learn that, but I did. I’m also about as capable of feeding myself as an infant drooling applesauce all over the floor. That was important to find out as well. We all must learn what we suck at. And the earlier in our life that we learn it, the better.

So we’re just bad at some things. Then there are other things that are great for a while, but begin to have diminishing returns after a few years. Traveling the world is one example. Sexing a ton of people is another. Drinking on a Tuesday night is a third. There are many more. Trust me.

Your limitations are important because you must eventually come to the realization that your time on this planet is limited and you should therefore spend it on things that matter most. That means realizing that just because you can do something, doesn’t mean you should do it. That means realizing that just because you like certain people doesn’t mean you should be with them. That means realizing that there are opportunity costs to everything and that you can’t have it all.

There are some people who never allow themselves to feel limitations — either because they refuse to admit their failures, or because they delude themselves into believing that their limitations don’t exist. These people get stuck in Stage Two.

These are the “serial entrepreneurs” who are 38 and living with mom and still haven’t made any money after 15 years of trying. These are the “aspiring actors” who are still waiting tables and haven’t done an audition in two years. These are the people who can’t settle into a long-term relationship because they always have a gnawing feeling that there’s someone better around the corner. These are the people who brush all of their failings aside as “releasing” negativity into the universe or “purging” their baggage from their lives.

At some point we all must admit the inevitable: life is short, not all of our dreams can come true, so we should carefully pick and choose what we have the best shot at and commit to it.

But people stuck in Stage Two spend most of their time convincing themselves of the opposite. That they are limitless. That they can overcome all. That their life is that of non-stop growth and ascendance in the world, while everyone else can clearly see that they are merely running in place.

In healthy individuals, Stage Two begins in mid- to late-adolescence and lasts into a person’s mid-20s to mid-30s.4 People who stay in Stage Two beyond that are popularly referred to as those with “Peter Pan Syndrome” — the eternal adolescents, always discovering themselves, but finding nothing.

Stage Three: Commitment

Once you’ve pushed your own boundaries and either found your limitations (i.e., athletics, the culinary arts) or found the diminishing returns of certain activities (i.e., partying, video games, masturbation) then you are left with what’s both a) actually important to you, and b) what you’re not terrible at. Now it’s time to make your dent in the world.

Stage Three is the great consolidation of one’s life. Out go the friends who are draining you and holding you back. Out go the activities and hobbies that are a mindless waste of time. Out go the old dreams that are clearly not coming true anytime soon.

Then you double down on what you’re best at and what is best to you. You double down on the most important relationships in your life. You double down on a single mission in life, whether that’s to work on the world’s energy crisis or to be a bitching digital artist or to become an expert in brains or have a bunch of snotty, drooling children. Whatever it is, Stage Three is when you get it done.

Stage Three is all about maximizing your own potential in this life. It’s all about building your legacy. What will you leave behind when you’re gone? What will people remember you by? Whether that’s a breakthrough study or an amazing new product or an adoring family, Stage Three is about leaving the world a little bit different than the way you found it.

Stage Three ends when a combination of two things happen: 1) you feel as though there’s not much else you are able to accomplish, and 2) you get old and tired and find that you would rather sip martinis and do crossword puzzles all day.

In “normal” individuals, Stage Three generally lasts from around 30-ish-years-old until one reaches retirement age.

People who get lodged in Stage Three often do so because they don’t know how to let go of their ambition and constant desire for more. This inability to let go of the power and influence they crave counteracts the natural calming effects of time and they will often remain driven and hungry well into their 70s and 80s.5

Stage Four: Legacy

People arrive into Stage Four having spent somewhere around half a century investing themselves in what they believed was meaningful and important. They did great things, worked hard, earned everything they have, maybe started a family or a charity or a political or cultural revolution or two, and now they’re done. They’ve reached the age where their energy and circumstances no longer allow them to pursue their purpose any further.

The goal of Stage Four then becomes not to create a legacy as much as simply making sure that legacy lasts beyond one’s death.

This could be something as simple as supporting and advising their (now grown) children and living vicariously through them. It could mean passing on their projects and work to a protégé or apprentice. It could also mean becoming more politically active to maintain their values in a society that they no longer recognize.

Stage Four is important psychologically because it makes the ever-growing reality of one’s own mortality more bearable. As humans, we have a deep need to feel as though our lives mean something. This meaning we constantly search for is literally our only psychological defense against the incomprehensibility of this life and the inevitability of our own death.6 To lose that meaning, or to watch it slip away, or to slowly feel as though the world has left you behind, is to stare oblivion in the face and let it consume you willingly.

What’s the Point?

Developing through each subsequent stage of life grants us greater control over our happiness and well-being.7

In Stage One, a person is wholly dependent on other people’s actions and approval to be happy. This is a horrible strategy because other people are unpredictable and unreliable.

In Stage Two, one becomes reliant on oneself, but they’re still reliant on external success to be happy — making money, accolades, victory, conquests, etc. These are more controllable than other people, but they are still mostly unpredictable in the long-run.

Stage Three relies on a handful of relationships and endeavors that proved themselves resilient and worthwhile through Stage Two. These are more reliable. And finally, Stage Four requires we only hold on to what we’ve already accomplished as long as possible.

At each subsequent stage, happiness becomes based more on internal, controllable values and less on the externalities of the ever-changing outside world.

Inter-Stage Conflict

Later stages don’t replace previous stages. They transcend them. Stage Two people still care about social approval. They just care about something more than social approval. Stage 3

people still care about testing their limits. They just care more about the commitments they’ve made.

Each stage represents a reshuffling of one’s life priorities. It’s for this reason that when one transitions from one stage to another, one will often experience a fallout in one’s friendships and relationships. If you were Stage Two and all of your friends were Stage Two, and suddenly you settle down, commit and get to work on Stage Three, yet your friends are still Stage Two, there will be a fundamental disconnect between your values and theirs that will be difficult to overcome.

Generally speaking, people project their own stage onto everyone else around them. People at Stage One will judge others by their ability to achieve social approval. People at Stage Two will judge others by their ability to push their own boundaries and try new things. People at Stage Three will judge others based on their commitments and what they’re able to achieve. People at Stage Four judge others based on what they stand for and what they’ve chosen to live for.

The Value of Trauma

Self-development is often portrayed as a rosy, flowery progression from dumbass to enlightenment that involves a lot of joy, prancing in fields of daisies, and high-fiving two thousand people at a seminar you paid way too much to be at.

But the truth is that transitions between the life stages are usually triggered by trauma or an extreme negative event in one’s life. A near-death experience. A divorce. A failed friendship or a death of a loved one.

Trauma causes us to step back and re-evaluate our deepest motivations and decisions. It allows us to reflect on whether our strategies to pursue happiness are actually working well or not.

What Gets Us Stuck

The same thing gets us stuck at every stage: a sense of personal inadequacy.

People get stuck at Stage One because they always feel as though they are somehow flawed and different from others, so they put all of their effort into conforming into what those around them would like to see. No matter how much they do, they feel as though it is never enough.

Stage Two people get stuck because they feel as though they should always be doing more, doing something better, doing something new and exciting, improving at something. But no matter how much they do, they feel as though it is never enough.

Stage Three people get stuck because they feel as though they have not generated enough meaningful influence in the world, that they make a greater impact in the specific areas that they have committed themselves to. But no matter how much they do, they feel as though it is never enough.8

One could even argue that Stage Four people feel stuck because they feel insecure that their legacy will not last or make any significant impact on the future generations. They cling to it and hold onto it and promote it with every last gasping breath. But they never feel as though it is enough.

The solution at each stage is then backwards. To move beyond Stage One, you must accept that you will never be enough for everybody all the time, and therefore you must make decisions for yourself.

To move beyond Stage Two, you must accept that you will never be capable of accomplishing everything you can dream and desire, and therefore you must zero in on what matters most and commit to it.

To move beyond Stage Three, you must realize that time and energy are limited, and therefore you must refocus your attention to helping others take over the meaningful projects you began.

To move beyond Stage Four, you must realize that change is inevitable, and that the influence of one person, no matter how great, no matter how powerful, no matter how meaningful, will eventually dissipate too.

And life will go on.

Footnotes

- Often this occurs because the adults/community themselves are still stuck in Stage One.↵

- Some people who get stuck in Stage One get stuck because they come to believe that they will never be able to fit in. These people usually succumb to some form of distraction, depression or addiction.↵

- I put normal in quotes because, really, what the fuck is normal?↵

- Stages can overlap to a certain extent. Transitioning between them is never black/white. It happens gradually. And often with some emotional stress and major lifestyle changes.↵

- This applies to the rare individuals who are talented and capable enough to still remain highly influential and relevant into their 70s and 80s as well. Stage Three doesn’t end until the desire for some peace and quiet outweighs one’s ability to affect change in the world. Some people die without ever leaving Stage Three.↵

- For more on this, see The Denial of Death by Ernest Becker.↵

- Research shows that generally people become happier and more satisfied as their lives go on.↵

- One way to think about it is that people who are stuck at Stage Two always feel as though they need more breadth of experience, whereas Stage Three people get stuck because they always feel as though they need more depth.↵

Complete Article HERE!

‘Adam Ruins Everything’ Takes on the American Funeral Industry

Adam Conover’s truTV show Adam Ruins Everything is airs the perfect episode this week: “Adam Ruins Death.” Among the death-related subjects Conover breaks down in the episode is how the American funeral industry takes advantage of grief for huge profits, and if Conover has his way, a whole lot of people will be making — or revising — their own funeral plans.

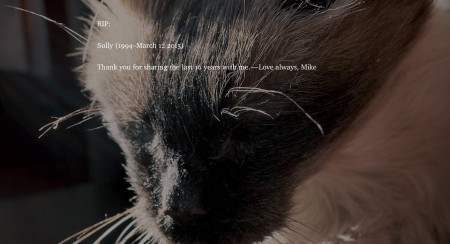

My Last Day

By Michael Henry

Unfortunately we all die, and today had to come. If anything it’s a relief. Between my old age and failing kidneys, every day was becoming increasingly uncomfortable — These last few weeks, especially. None the less, I did my best to enjoy each and every day.

Since today could not be avoided, we decided to make an event out of it. Who doesn’t want to spend their last moments having a good time with loved ones?

My Breakfast

You can’t start any day without a healthy breakfast — let alone second breakfast, or elevensies, but I digress. Today was no exception, but we had to take it over the top.

You can’t start any day without a healthy breakfast — let alone second breakfast, or elevensies, but I digress. Today was no exception, but we had to take it over the top.

My human, Michael, made me a wonderful decadent breakfast with my favorite things: Fancy Feast Gravy Lovers (Beef) with Archetype powered rabbit mixed in. It may not sound great to you, but YUM!

Sunbathing

I think I overate. So good. So full. Need to relax.

Look! The sun!

Oh wait, I am in the middle of telling a story…

Brushing and reminiscing

Once I recovered from my breakfast-sun coma, I spent some time with my humans, Mike and Tracy. They brushed me, petted me, and we talked about my life.

We talked about how I was born in New York City in 1994.

We talked about my first human, Sui and how much I miss her. I used to climb up the ladder of her loft bed, in the East Villiage. I’d follow her too close and occasionally she’d end up stepping on me. She made an awesome t-shirt based on me.

We talked about how my human, Michael, won my heart with his constant affection. I claimed him as mine in 1999 — When he would go to work, he would pet me goodbye. The day I decided he was mine, I grabbed his hand when he went to leave, and pulled him back. Literally! I didn’t want to let him go, and stayed with him the next 16 years.

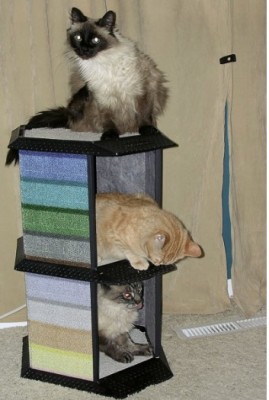

We talked about my bully of a brother, Mulder (1994–2009), who I still loved, and miss. He was always the outgoing one, and twice my size. He wasn’t so bad most of the time, but occasionally he was so mean to me.

We talked about moving to Colorado and all the years there.

We talked about the years with the dog, Ripley (2005-?) — I never liked him. He was never mean to me, he was just a dog. Tried to smell my butt all the time. Ick!

We talked about my adopted sister, Newt (2006–2009). She was annoying, but truly I didn’t mind her as much as I let on. Such a young ball of energy, and sadly lived up to the bit about curiosity and cats.

We also talked about moving to Seattle, and how I decided to stop being so shy. One day I was curious, so started going out and introducing myself to people. It was amazing!

We talked about my final human, Tracy. She was reluctant, at first. Eventually I won her over and claimed her as mine. She was always so affectionate to me. She was always there to help Michael take care of my health needs this last year.

After so much talking and affection, I needed a break

Resting and Health

When cats get as old as I do, it often comes with health complications. I’m certainly no exception. because of it, I need to rest. More and more every day.

After a year, I’m barely able to walk any more. My body aches and I’m so tired. After a final vet visit, we discovered my kidneys are in the final stages of failure. At this point my health is declining by the day. Don’t even remind me of the grand-mal seizures, they suck!

Rather than have me slowly suffer over the next few weeks (at most), we decided to have a relatively happy ending.

Final Moments

Not long after getting into my bed did I finally fall asleep. I was so tired from the day’s activities that I didn’t even awake when the vet arrived. That’s a good thing, it would have made me anxious.

While laying there I felt a prick on my side. By time I realized what was happening, the drugs were already sedating me.

After that, Michael picked me up one last time, and held me as a drifted away.

Final Thoughts

One of the things Michael always loved about me is that no matter how tough life was for us, I was always affectionate and loving. I always adapted, and tried to make the best of a situation, faster than any other cat he’s known.

If you don’t try to enjoy every good moment, why bother living? We should enjoy every moment we get.

Oh yeah, and and last night I left a gift for my humans to remember me by. Don’t ruin the surprise!

Complete Article HERE!

Why Humans Care for the Bodies of the Dead

By Julie Beck

In tracing the history and culture of corpses, a new book shows the importance of remembrance to our species.

The ancient Greek Cynic philosopher Diogenes was extreme in a lot of ways. He deliberately lived on the street, and, in accordance with his teachings that people should not be embarrassed to do private things in public, was said to defecate and masturbate openly in front of others. Plato called him “a Socrates gone mad.” Shocking right to the end, he told his friends that when he died, he didn’t want to be buried. He wanted them to throw his body over the city wall, where it could be devoured by animals.“What harm then can the mangling of wild beasts do me if I am without consciousness?” he asked.What is a dead body but an empty shell?, he’s asking. What does it matter what happens to it? These are also the questions that the University of California, Berkeley, history professor Thomas Laqueur asks in his new book The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains.“Diogenes was right,” he writes, “but also existentially wrong.”

This is the tension surrounding how humans treat dead bodies. What makes a person a person is gone from their bodies upon death, and there’s really no logical reason why we should care for the empty container—why we should embalm it, dress it up, and put it on display, or why we should collect its burnt remnants in an urn and place it on the mantle.

Humanity’s answer to Diogenes, Laqueur writes, has largely been “Yes, but…” People have cared for the bodies of their dead since at least 10,000 B.C., Laqueur writes, and so the reason for continuing to do so is a tautology: “We live with the dead because we, as a species, live with the dead.” And the fact that we do so, he argues, is one of the things that brings us as a species from nature into culture. (The taboo against incest is another example.)Despite the rationality of Diogenes’s logic, it’s unthinkable that we would just throw the corpses of our loved ones over a wall and leave them to the elements. Dead bodies matter because humans have decided that they matter, and they’ve continued to matter over time even as the ways people care for bodies have changed.

Laqueur’s book makes this argument with a dense, detailed sketch of a relatively small slice of time and space: Western Europe from the 18th to 20th centuries. The story begins with churchyards, which “held a near monopoly on burial throughout Christendom … for more than a thousand years, from the Middle Ages to the early 19th century and beyond in some places.” People would be buried (and generally had a legal right to be buried) in the yard of the church of the parish where they lived (or in the church itself if they were wealthy or clergy). This was a messy business. The yards were constantly being churned up as new bodies were buried, and they got lumpy. There weren’t many grave markers, and if there were, they were likely to read “here lies the body,” not a particularly personal epitaph.

“The churchyard was and looked to be a place for remembering a bounded community of the dead who belonged there,” Laquer writes, “rather than a place for individual commemoration and mourning.”Though bodies were jumbled together in churchyards in a way that it made it almost impossible to find any one individual, there was some method to their arrangement: They were buried very deliberately along an east-west axis to line up with Jerusalem to the east, the direction from which the resurrection was expected to come. John Calvin, the Protestant theologian, thought the very act of burial showed faith in a corporeal resurrection.

In the early 19th century, the dominance of churchyards began to wane, for a number of reasons. They were crowded, for one. Rotting bodies piled up in churchyards and church vaults also produced the kind of odor you might expect, and activists began to argue that they were unsanitary. But Laqueur points out that churchyards had always been crowded and smelly, and “for centuries the smell … was tolerable.” The rise of cemeteries as an alternative to churchyards, Laqueur writes, was really part of a massive cultural shift, one that owed a lot to the industrial revolution and the Protestant reformation.

During and after industrial revolution, unpleasant things of all kinds were being removed from people’s sight. Butchers and slaughterhouses delivered meat while keeping the blood behind the curtain; London constructed a massive sewer system, getting people’s waste off the streets and out of the River Thames. With this as the backdrop, it stands to reason that people might want the dead bodies out of their cities as well—while they didn’t pose a real public-health threat, people successfully argued that they did, and that was enough.

The first great cemetery of the West was Père-Lachaise in Paris, built by Napoleon, and it inspired the building of others in Copenhagen, Glasgow, and Boston, among other cities. Unlike churchyards, these cemeteries were stand-alone places for the dead, open to the public and largely separated from the crowded areas of cities.They were also disassociated from religion. “To some degree this is about the rise of negative liberty: the right to a grave in a neutral civic space irrespective of one’s beliefs or lack of beliefs, and the right to a choice in rituals of burial,” Laqueur writes. The waning dominance of the Catholic Church had a lot to do with that. Burying bodies right by the church would remind people on their way in to pray for the dead as a way of helping those souls stuck in purgatory. But many Protestant reformers rejected the idea of purgatory, and argued that the dead did not need the prayers of the living.

The focus of cemeteries was not, as it had been in churchyards, on a community of faithful dead, but on remembering the individual. It allowed for families to be buried together, which hadn’t really been possible in the tangle of the churchyard.

“It was a place of sentiment loosely connected, at best, with Christian piety and intimately bound up with the emotional economics of family,” Laqueur writes. “In it, a newly configured idolatry of the dead served the interests less of the old God of religion than of the new gods of memory and history: secular gods.” Cemeteries allowed for gravestones, monuments, epitaphs, the carving of names in stone. This provides a little insurance against the fear of death—that one’s name, at least, will outlast them. Carving in stone is a powerful metaphor for permanence, even if it’s just wishful thinking.

The advent of cremation as a popular practice took some of this enchantment away from the dead body. But while in some ways people who opted for cremation were finally recognizing the body as a shell, just like Diogenes said, deference towards bodies was often just replaced by deference to its ashes. Ashes are scattered, interred, and revered in many ways, just as bodies are. And cremation has obviously not completely replaced burial by any stretch.If care for the dead is one of the quintessential things about being human, fear of death is another. Being the only animal with constant awareness of its own mortality has significant effects on how humans behave. Often, according to terror-management theory, the thought of death will lead people to seek out and to value more highly things that they think will bring them immortality, in the metaphoric sense. Living on in the memories of others would do the trick, even though we must on some level know is only a reprieve against eventually being forgotten.On this matter, Laqueur turns to the 17th-century poet John Weever:

Every man, Weever writes, “desires a perpetuity after his death.” Without this idea “man could never have awakened in him the desire to live in the remembrance of his fellows.” And without it, human life in the shadow of death would be unbearable and unrecognizable: “the social affections could not have unfolded themselves un-countenanced by the faith that Man is an immortal being.” Our love for one another differs from the love animals might feel for one another in that an animal perishes in the field without “anticipating the sorrow with which is associates will bemoan his death,” whereas we “wish to be remembered by our friends.” Naming the dead, like care for their bodies, is seen as a way to keep them among the living. And maybe it is a way around Diogenes.

So yes, Diogenes, the body is technically nothing once void of its soul, or consciousness, or however one conceives of the essence of a person. We get it. But it’s a physical emblem of that person, and in caring for it, we offer the person’s memory a chance to linger, as we hope our own will.

Even if physical death is quick and final, social death takes time. And through communal effort, people offer each other the chance for their names to last a little longer on Earth than their bodies do. “There is also another way to construe the dead,” Laqueur writes: “As social beings, as creatures who need to be eased out of this world and settled safely into the next and into memory.”

Complete Article HERE!