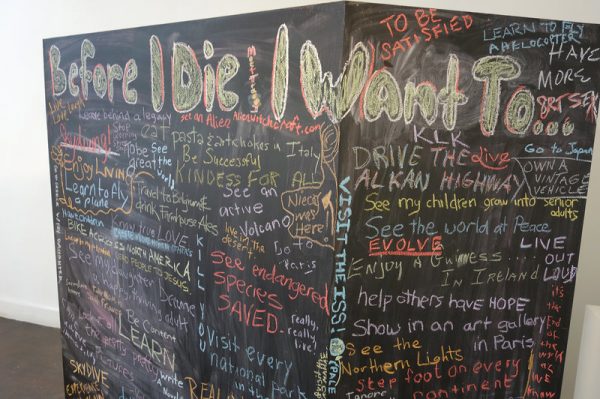

Managing emotional and physical pain is the most difficult part of end-of-life care. You can learn to face the worst, when it comes, with dignity and grace. Make the necessary arrangements ahead of time and make the most of the time you have left.

1. Talk to your doctor about your pain management options.

It’s important to make your physical comfort a high priority in end-of-life care. Depending on your condition, you may be taking a variety of medications, or undergoing a variety of different procedures, so it’s important to discuss all treatment options with your doctor and ensure your comfort is provided in addition to these considerations.

- Morphine is commonly prescribed to terminal patients, sometimes on a constant need-basis. While there’s some debate about whether or not morphine may shorten your life span, it’s efficacy as a powerful pain-reliever is proven. If you’re in serious pain, talk to your doctor about the option.[1]

- In some cases, it may be appropriate to pursue additional non-traditional methods of pain management, like holistic medicine, medical marijuana, or other non-western treatments. As long as these treatments don’t get in the way of other care you’re receiving, it’s likely they’ll be approved by your doctor, and might be worth a shot.[2]

2. Be at home as much as possible.

While not everyone has the luxury of paying for home palliative care, you should think about what will bring you the most comfort and peace in your particular situation. There may be more help available in a hospital but you may feel more comforted and peaceful in your own home.

- If you’re able to leave the hospital, try to get out as much as possible. Even going for short walks can help to get away from the beeping of hospital machines and be a nice change of pace.

3. Address the symptoms of dyspnea quickly.

Dyspnea, a general term for end-of-life breathing difficulties, can affect your ability to comfortably communicate, leading to frustration and discomfort. It’s something you can address and care for yourself, with some simple techniques.

- Keep the head of your bed raised and keep the window open, if possible, to keep fresh air circulating as much as possible.

- Depending on your condition, it may also be recommended to use a vaporizer, or to have additional oxygen supplied directly, through the nose.

- Sometimes, fluid collection in the throat can result in ragged breathing, which can be aided by turning to one side, or by a quick clearing procedure your doctor can perform.

4. Address skin problems.

Facial dryness and irritation from spending lots of time in a prone position can be an unnecessary discomfort in end-of-life scenarios. As we get older, skin problems become more significant, making them important to address swiftly.

- Keep your skin as clean and moisturized as possible. Use lip balm and non-alcoholic moisturizing lotions to keep chapped skin softened. Sometimes damp cloths and ice chips can also be effective at soothing dry skin or cotton mouth.

- Sometimes called “bed sores,” pressure ulcers can result from prolonged time in a prone position. Watch carefully for discolored spots on the heels, hips, lower back, and neck. Turn from side and back every few hours to help prevent these sores, or try putting a foam pad under sensitive spots to reduce pressure.

5. Try to manage your energy levels.

The routine of being in the hospital will take a toll on anyone, and the constant blood pressure checks and IV drip can make it difficult to sleep. Be honest about your energy levels, any nausea, or temperature sensitivity you’re experiencing to get as much rest to be as energetic as possible.

- Occasionally, in end-of-life scenarios, medical staff will discontinue these types of routines, when they become unnecessary. This can make it much easier to relax and get the rest you need to stay energetic and somewhat active.

6. Ask questions and stay informed.

It can get quickly overwhelming, confusing, and frustrating to be in the hospital and feel like you’re not in control of your own life anymore. It can be very helpful emotionally to stay as informed as possible by using your doctor questions regularly. Try to ask these types of questions to the doctor in charge:

- What’s the next course of action?

- Why do you recommend this test or treatment?

- Will this make me more comfortable, or less?

- Will this speed up or slow down the process?

- What does the timetable for this look like?

Tomorrow, Part 2 — Making Arrangements

Complete Article HERE!