The price of a humanity that actually grows and changes is death.

[P]eople still sometimes discuss the question of how you could tell that you were talking to some form of artificial intelligence rather than an actual human being. One of the more persuasive suggested answers is: “Ask them how they feel about dying.” Acknowledging that our lifespan is limited and coming to terms with this are near the heart of anything we could recognise as what it means to be human.

Once we discovered that Neanderthals buried their dead with some ritual formality, we began to rethink our traditional species snobbery about them and to wonder whether the self-evident superiority of homo sapiens was as self-evident as all that. Thinking about dying, imagining dying and reimagining living in the light of it, this is – just as much as thinking about eating, sex or parenting – inseparable from thinking about our material nature – that to have a point of view at all we have to have a physical point of view, formed by physical history. Even religious systems for which there is a transition after death to another kind of life will take for granted that whatever lies ahead is in some way conditioned by this particular lifespan.

Conversely, what the great psychoanalytic thinker Ernest Becker called “the denial of death” is near the heart of both individual and collective disorders: the fantasy that we can as individuals halt the passage of time and change, and the illusions we cherish that the human race can somehow behave as though it were not in fact embedded in the material world and could secure a place beyond its constraints. Personal neurosis and collective ecological disaster are the manifest effects of this sort of denial. And the more sophisticated we become in handling our environment and creating virtual worlds to inhabit and control, the looser our grip becomes on the inexorable continuity between our own organic existence and the rest of the world we live in.

It’s a slightly tired commonplace that we moderns are as prudish in speaking about death as our ancestors were in speaking about sex. But the analogy is a bit faulty: it’s not simply that we are embarrassed to talk about dying (although we usually are), more that we are increasingly lured away from recognising what it is to live as physical beings. As Kathryn Mannix bluntly declares at the beginning of her book about pallia-tive care, “It’s time to talk about dying”. That is if we’re not to be trapped by a new set of superstitions and mythologies a good deal more destructive than some of the older ones.

Each of these books in its way rubs our noses in physicality. Caitlin Doughty’s lively (and charmingly illustrated) cascade of anecdotes about how various cultures handle death spells out how contemporary Western fastidiousness about dead bodies is by no means universally shared. We are introduced to a variety of startling practices – living with a dead body in the house, stripping flesh from a relative’s corpse, exhuming a body to be photographed arm in arm with it… all these and more are routine in parts of the world. And pervading the book is Doughty’s ferocious critique of the industrialisation of death and burial that is standard in the United States and spreading rapidly elsewhere.

Doughty invites us to look at and contemplate alternatives, including the (very fully described) composting of dead bodies, or open-air cremations. A panicky urge to get bodies out of the way as dirty, contaminated and contaminating things has licensed the development of a system that insists on handing over the entire business of post-mortem ritual to costly and depersonalising processes that are both psychologically and environmentally damaging (cremation requires high levels of energy resource, and releases alarming quantities of greenhouse gases; embalming fluid in buried bodies is toxic to soil). Doughty has pioneered alternatives in the US, and her book should give some impetus to the growing movement for “woodland burial” in the UK and elsewhere. At the very least, it insists that we have choices beyond the conventional; we can think about how we want our dead bodies to be treated as part of a natural physical cycle rather than being transformed into long-term pollutants, as lethal as plastic bags.

Talking about choices and the reclaiming of death from anxious professionals takes us to Kathryn Mannix’s extraordinary and profoundly moving book. Mannix writes out of many years’ experience of end-of-life care and presents a series of simply-told stories of how good palliative medicine offers terminally ill patients the chance of recovering some agency in their dying. Those who are approaching death need to know what is likely to happen, how their pain can be controlled, what they might need to do to mend their relationships and shape their legacy. And, not least, they need to know that they can trust the medical professionals around to treat them with dignity and patience.

Mannix’s stories are told with piercing simplicity: and there is no attempt to homogenise, to iron out difficulties or even failures. A recurrent theme is the sheer lack of knowledge about dying that is common to most of us – especially that majority of us who have not been present at a death. Mannix repeatedly reminds us of what death generally looks like at the end of a degenerative disease, carefully underlining that we should not assume it will be agonising or humiliating: again and again, we see her explaining to patients that they can learn to cope with their fear (she is a qualified cognitive behavioural therapist as well as a medical professional). It is not often that a book commends itself because you sense quite simply that the writer is a good person; this is one such. Any reader will come away, I believe, with the wish that they will be cared for at the end by someone with Mannix’s imaginative sympathy and matter-of-fact generosity of perception.

Sue Black’s memoir is almost as moving, and has something of the same quality of introducing us to a few plain facts about organic life and its limits. She moves skilfully from a crisp discussion of what makes us biologically recognisable as individuals and how the processes of physical growth and decay work to an account of her experience as a forensic anthropologist, dedicated to restoring and making sense of bodies whose lives have ended in trauma or atrocity. The most harrowing chapter (and a lot of the book is not for those with weak stomachs) describes her investigations at the scene of a massacre in Kosovo: it is a model of how to write about the effect of human evil without losing either objectivity or sensitivity.

Perhaps what many readers will remember most vividly is her account of her first experience of working as a student with a cadaver. For all the stereotypes of the pitch-dark and tasteless humour of medical students in this situation, the truth seems to be that a great number of them actually develop a sense of relatedness and indebtedness to the cadavers they learn on and from. Black writes powerfully about the sense of absorbing wonder, as the study of anatomy unfolds, of the way in which it reinforces an awareness of human dignity and solidarity – and of feeling “proud” of her cadaver and of her relation with it.

For what it’s worth, having taken part in several services for relatives of those who have donated their bodies to teaching and research, I can say that the overwhelming feeling on these occasions has been what Black articulates: a moving mutual gratitude and respect. And the book is pervaded by the sense of fascinated awe at both the human organism and the human self that comes to birth for her in the dissecting room.

Richard Holloway writes not as a medical professional but as a former bishop, now standing – not too uneasily – half in and half out of traditional Christian belief, reflecting on his own mortality and the meaning of a life lived within non-negotiable limits. His leisurely but shrewd prose – with an assortment of poetic quotation thrown in – is a good pendant to the closer focus of the other books, and he echoes some of their insights from a very different perspective. Medicine needs to be very wary indeed of obsessive triumphalism (the not uncommon attitude of seeing a patient’s death as a humiliation for the medical professional); the imminence of death should make us think harder about the possibility and priority of mending relations; the fantasy of everlasting physical life is just that – not a hopeful prospect, but the very opposite.

He has some crucial things to say about the politics of the drive towards cryogenic preservation. Even if it were possible (unlikely but at best an open question) it is something that will never be available to any beyond an elite; any recovered or reanimated life would be divorced from the actual conditions that once made this life, my life, worth living; how would a limited physical environment cope with significant numbers of resuscitated dead? The book deserves reading for these thoughts alone, a tough-minded analysis of yet another characteristic dream of the feverish late-capitalist individual, trapped in a self-referential account of what selfhood actually is.

****

Odd as it may sound, these books are heartening and anything but morbid. Mannix’s narratives above all show what remarkable qualities can be kindled in human interaction in the face of death; and they leave you thinking about what kind of human qualities you value, what kinds of people you actually want to be with. The answer these writers encourage is “mortal people”, people who are not afraid or ashamed of their bodies, those bundles of rather unlikely material somehow galvanised into action for a fixed period, and wearing out under the stress of such a rich variety of encounter and exchange with

the environment.

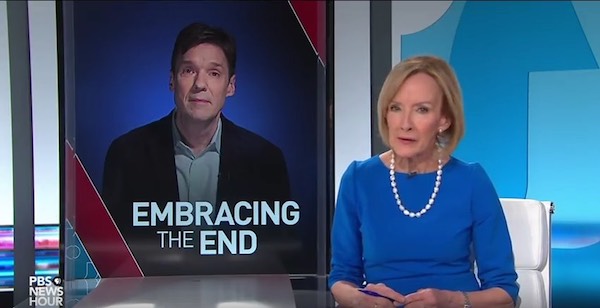

None of these books addresses at any great length the issues of euthanasia and assisted dying, but the problem is flagged: Black says briskly that she hopes for a change in the law (but is disarmingly hesitant when it comes to particular cases), while Mannix, like a large number of palliative care professionals, strikes a cautionary note. She tells the story of a patient who left the Netherlands for the UK because he had become afraid of revealing his symptoms fully after being (with great pastoral sensitivity and kindness) encouraged by a succession of doctors to consider ending his life. “Be careful what you wish for,” is Mannix’s advice; and she is helpfully clear that there are real options about the ending of life that fall well short of physician-assisted suicide.

Like all these authors, she warns against both the alarmist assumption that most of us will die in unmanageable pain and powerlessness and the medical amour propre that cannot discern when what is technically possible becomes morally and personally futile – when, that is, to allow patients to let go. The debate on assisted dying looks set to continue for a while yet; at least what we have here goes well beyond the crude slogans that have shadowed it, and Mannix’s book should lay to rest once and for all the silly notion occasionally heard that palliative care is a way of prolonging lives that should be economically or “mercifully” ended.

The most important contribution these books make is to keep us thinking about what exactly we believe to be central to our human condition. It is not a question to answer in terms simply of biological or neurological facts but one that should nag away at our imagination. How do we want to be? And if these writers are to be trusted, deciding that we want to be mortal is a way of deciding that we want to be in solidarity with one another and with our material world, rather than struggling for some sort of illusory release.

Richard Holloway doesn’t quite say it in these terms, but the problem of a humanity that doesn’t need to die is that it will be a humanity that needs no more births. The price of a humanity that actually grows and changes is death. The price of eternal life on earth is an eternal echo chamber. As someone once said around this time of year: “Unless a grain of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed.”

Waiting for the Last Bus: Reflections on Life and Death

Richard Holloway

Canongate, 176pp

All that Remains: a Life in Death

Sue Black

Doubleday, 368pp

From Here to Eternity: Travelling the World to Find the Good Death

Caitlin Doughty

Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 272pp

With the End in Mind: Dying, Death and Wisdom in an Age of Denial

Kathryn Mannix

William Collins, 352pp

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!