By Diane Rehm

Martha Kay Nelson has had a long career in hospice work. Rather than choosing hospice work, she believes hospice work chose her. Her training was at Harvard Divinity School. She did a yearlong internship as a hospice chaplain during her graduate work. The year after she graduated, she managed to combine her career as a chaplain with her work in hospice. She is in her mid-forties, with short hair and hazel eyes. Her warm, open face, earnest manner, and easy smile help me understand why she is so good at her work. We sit together in her office at Mission Hospice & Home Care in San Mateo, California.

DIANE: How do you feel about California’s “right to die” law?

MARTHA: Well, I have many feelings, and they could vary depending on the day or the hour. It depends on whom I’m talking to, and what her or his experience is. My overall sense about the law is that people have a right to make their own health-care decisions, whether it’s at the end of life or at any time up to that point. I know people have a hard time having these conversations, particularly early on, before they’re even sick. And then they get sick and it’s crisis time, and those decisions have to be made quickly. The End of Life Option Act to me is part of a spectrum of all those decisions and conversations that come at the end. It’s a new end point on that spectrum.

D: You’ve been in a leadership position here at Mission Hospice, not only learning, but teaching. Tell me what have been the elements of transmitting this information to others.

M: It’s been an interesting learning curve. I think even seasoned hospice professionals have had to adjust to a new option for patients, stepping into that terrain. The elements that have been important in teaching staff members, working with health-care partners, have been to get folks to acknowledge at the outset that this is a challenging topic, this is new terrain, there are profound implications, and not to shy away from it.

Some folks here at Mission Hospice didn’t want to participate, but the majority did, to have their questions answered or share some of their thoughts, their concerns. We’ve done this regularly enough that people felt they could talk freely about the End of Life Option Act. We didn’t want it to be whispered about awkwardly in the corner, that this law is coming and our patients are going to have the right to choose the option. As an agency, we’re not advocates for the law, we’re advocates for our patients, and we won’t abandon them. Having said that, any of our employees, if they’re not comfortable, don’t have to participate. They can opt out if they need to, and they would be fully supported.

D: What kinds of questions did you get from staff? What kinds of issues did they raise?

M: At the outset, a lot of general questions about details of the law, how it works, how are we supposed to communicate with our colleagues around it, what can we say to the patient and what can’t we, those kinds of things. Questions arose about accessibility to the law. If I have patients who are saying they just want to end it all, and they’re saying this a lot, but they’re not specifically asking about the law, then can I bring it up with them or not? We have a policy here at Mission Hospice that we let the patient lead. If a patient is inquiring about his or her options, then we will be there.

That’s one kind of question. Other clinicians have asked about folks who haven’t had the chance to be educated about medical aid in dying, or don’t have access to resources where they might have learned about it. What if it’s something they’d like to avail themselves of ? There’s kind of a social justice question there. There are also questions arising from specific cases. Every case is different.

D: Can you give me an idea of how many patients have actually come forward and asked you about the right to die?

M: We’ve been tracking some of these numbers, and to date, we’ve served around forty-five people since California’s law went into effect, which was a lot more than we anticipated. When back in 2016 we set out to draft our policy and prepare ourselves, we thought maybe we’d have four or five people in the first year. We had twenty-one. And about that same number inquired about the law, but never went all the way through the process. Either they actually died before they had a chance to use the law, or they changed their minds. I would imagine that it was split evenly.

D: Tell me about the process. So a patient comes to you and asks about the process, the law. How do you respond?

M: My initial response as a chaplain would be one of curiosity. I’d be interested in learning more about their thoughts and why they’re asking. It’s a big thing to ask about. Sometimes people are afraid to even inquire. They’re afraid of being shamed or judged. So I’d want to let that person know that I’m glad they’re asking. And then we’d have a conversation, whatever they would wish to say at that time. Next, I would contact the doctor and the rest of my interdisciplinary team members and would let them know the topic had been broached. Then a doctor would probably go and make a direct visit, which would be considered the first formal request, if the decision was made to pursue that course.

We really encourage the other team members to make sure they keep talking to one another—the social worker, the nurse, the spiritual counselor, home health aides, and volunteers who might also be involved. Through a team effort, we would need to have clarity on how much privacy the patient would want. Patients have the right under the law to not tell anyone but the doctors they’re working with, not even family members. Our experience has been that that’s not often the case. Usually there is communication with family.

D: Who makes the initial judgment that the patient has six months or less to live?

M: The attending physician on the case. And if the patient inquires about the law, and his or her doctor says, “I’m not comfortable being involved with this,” that’s one way we might get involved. Or it might be a hospice patient already on our service.

D: I saw in your waiting room a brochure for Death Cafes. Can you tell me about them?

M: The Death Cafe movement started several years ago in England. It’s basically having a conversation over coffee and cakes in a public venue. Anyone is welcome to attend, and the purpose is open-ended. The goal is to talk about death in any way you wish. There does need to be a facilitator, someone who is able to establish ground rules in etiquette so folks aren’t talking over one another. Folks that host them tend to have some level of experience in end-of- life care, in thanatology, but anyone can sign up. I’ve led a couple of them.

D: How successful do you think Death Cafes are as teaching tools, as comforting elements in the whole discussion of death?

M: I think Death Cafes are successful in meeting the needs of folks who already want to talk about death. If you show up at a Death Cafe, there’s something in you that is already ready to speak and to hear what other people are thinking. It can serve as a cross-pollination of ideas and thoughts, and normalization. The cafes meet a kind of thirst that we have in our culture to speak about these things openly and not be afraid. How you get people to Death Cafes is another question. I’ve had some people say they’re offended by that name, or they don’t want to attend a Death Cafe because it sounds morbid.

D: What is the best way to reach people? How do we get the conversation started even before we’re sick?

M: There’s no one best way. It’s about being creative and really getting to know your community. In my family, I’ve been lucky in that we’ve always talked about death openly. I have ongoing conversations now with my father. He’s about to turn eighty-three, and I really value the kinds of discussions and ruminations we have.

It’s wonderful. We’ve started kind of reflecting theologically, talking about, wondering together, what happens after we die. To be able to have that in a father-daughter kind of way. I’m well aware of what a precious opportunity it is to hear his thoughts. As he comes into the “lean and slippered pantaloon” time of his life, as he might say—some of his last chapters— I feel really blessed that he’s willing to discuss it openly.

D: How do you open that discussion for the general public?

M: I think it takes courage and a conscious decision to ask a question of someone in a moment when you feel there’s an opportunity. Someone speaking about her or his health, some decline, or illness, grief, and you ask, “How would you like things to be?” And perhaps even being a bit persistent if you get an initial brush-off, which often happens, but trying again, and saying, “ Really, I would like to know.”

I also think reaching children is important. I think that in our death-denying culture, children are really shielded from all things involved with death. Things happen at the funeral parlor, no longer at home, and we try to protect children in all kinds of ways. But if you don’t allow children who want to be involved in a loved one’s illness or death, I think you’re doing them a disservice. You’re keeping them from something that is integral to life for all of us. The earlier you can start to have those experiences and wonder about them and ask the questions, the more skills you will have as you age to meet them openly.

D: Have you decided what you want for yourself at the end?

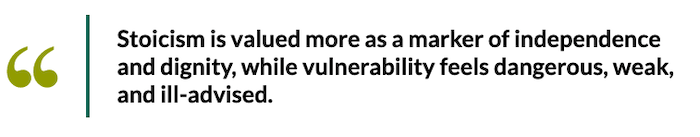

M: I have no idea. I do know that I would like to have the right and the option to choose. I understand that even just knowing that the option is available can bring a lot of comfort to people. I haven’t faced a terminal illness that might cause me great physical pain or suffering, or mental or spiritual suffering. There’s one area that gives me pause, which is when folks choose medical aid in dying because they’re used to being in control in their lives. They might not have physical or mental or spiritual suffering, but they want to have personal agency. I think they entirely have the right to do that. But I also believe we’re in a culture that distorts the degree to which we think we’re in control. So on a soul level, on a much deeper level, I wonder, Are we messing with something there? How is it that we’re making such a profound decision from a place of a distorted need for control? And then I think, Well, what do I know about their journey and what they need? Maybe this is the one time they’ve ever made a strong, solid decision for themselves, and who am I to say what it is they need to learn?

D: But isn’t pain, intractable pain and suffering, and the inability to care for oneself, a sufficient reason to respect someone’s decision in terms of his or her final say?

M: Absolutely. I think clinicians have more trouble when they can’t observe visible intractable pain, when they can’t see physical or emotional suffering. It’s harder for clinicians to get their heads and hearts around that. Why is someone making this choice? And so I do a lot of counseling with staff about that, exploring how to meet the needs of the person when we don’t see them suffering, at least not on the surface. And we have to remind ourselves, clinicians need to express those feelings and concerns, so that when they’re dealing with patients directly, they can be respectful and meet them on their own terms.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!